Pastor’s research into a mysterious family ‘accident’ along Perry Lake is now a true-crime book

photo by: Contributed

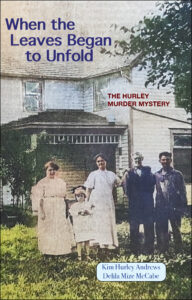

A cover of the novel “When the Leaves Began to Unfold: The Hurley Murder Mystery.” The novel, written by KU graduate Kim Andrews, details a triple murder that happened in to her family near Perry Lake in the 1920's that received national attention.

When Kim Andrews was in high school, she learned for the first time about a literally explosive family story — one that she has been working to tell, on and off, for the past 30 years.

Andrews, on a trip with her father to Topeka, met with a cousin who took them up to a farm site on Perry Lake in Jefferson County. Once there, she learned about a triple murder that occurred on her great-grandfather’s farm in 1923 and was discovered after a neighbor passing by on that rainy May night heard an explosion and saw a fire engulf the house.

Andrews and her family had always heard that the tragedy that left her great-grandfather, his daughter and his youngest son dead was an accident. But after digging through archives at the Kansas Historical Society and speaking with locals around Perry Lake, she uncovered a story full of rumors, suspicions and fascinating characters and details that sometimes felt stranger than fiction.

“They never really could figure out exactly what happened, and nobody will ever know,” Andrews said. “But boy, it sure is a good story.”

So good, in fact, that she thought it should be published for the world to read. Andrews began the project of telling the story in a book in 1992 when she met Lila McCabe, who wrote a short story about the fire, and the two decided to collaborate. It took decades of work, but now Andrews, who is now a pastor, was able to publish the true-crime book earlier this year under the title “When the Leaves Began to Unfold: The Hurley Murder Mystery.”

photo by: Contributed

Kim Andrews

• • •

When investigators started looking into the Hurley farmhouse explosion in 1923, they quickly found three bodies: Andrews’ great-grandfather Thomas; his daughter Genevieve, 41 years old; and his youngest son Ernest, 28, a newlywed.

And, when Andrews and her father pored over newspaper reports in the volumes of microfiche at the Kansas Historical Society, they found that contemporary accounts were not convinced it was an accident.

“People who investigated it weren’t satisfied by the investigation,” Andrews said. “It wasn’t a straightforward case.”

Part of that was because the Hurleys were not a straightforward family. They had lived in Jefferson County since the 1860s, and the family was a large one with 13 kids. Andrews said in her research, she found that many of the women in the family were described as “hot headed” — and she, like some others who looked into the case, began to suspect that one of them had gotten up to some foul play.

That would be Genevieve, who was Andrews’ great-aunt. Andrews, referring to her as “Jennie,” said she wasn’t a typical woman of that era.

Described in reports at the time as “talented and beautiful,” Jennie had worked in Kansas City, Kansas, at Horace Mann Elementary School as a teacher and even principal before moving back to Jefferson County. She was unmarried at the time of the incident, but had multiple suitors, including two fiances: one who lived nearby and one who was a railroader in Iowa or Nebraska, Andrews said.

She also at one point showed one of the suitors, who was a farmer, multiple different rings, which led him to believe she might have previously been engaged.

Investigators at the time apparently tried to trace the whereabouts of Jennie’s suitors to no avail, but there were other details that raised suspicion, too. Andrews said the rings that the farmer was apparently shown were never recovered, meaning someone could have taken them or they might not have existed to begin with. Guns that were normally stored in specific locations wound up in the middle of the house, and shell casings were found in the aftermath of the fire. Did they explode from the fire, or were they fired before it started?

Additionally, investigators found blood under at least one of the male victims, and Andrews said there was supposedly a very small section of Jennie’s midriff found on the scene.

There were also rumors of a cadaver being stolen from what is now the KU Medical Center a week before the fire and deaths, Andrews said. That led some people to speculate that perhaps the body that investigators thought was Jennie’s wasn’t actually hers.

The flames of that story were fanned by a reporter who submitted a sensationalized account to a Hearst newspaper insert called “The American Weekly.” It was inserted in newspapers in big and small cities across the country, with an illustration “that depicted Genevieve Hurley dragging a woman’s body in a sheet,” Andrews said.

There were some credible sightings of Jennie reported after the fire, but Andrews said it’s likely that the truth about what happened to her will never be fully known.

Some of Andrews’ interest in the story came from wanting to find that truth, or to get closer to it. But she also said she wanted to depict the people in the book as people, not caricatures, and to not focus on some of the gruesome details.

“I wanted to do it respectfully. This was my family; they are human beings deserving of dignity, no matter what,” Andrews said.

• • •

photo by: Courtesy: Rock Creek Marina

Rock Creek Marina on Perry Lake is pictured.

The old farm site by the lake was a place that Andrews was often drawn to — not just for its mystery, but as an escape from her everyday life.

Andrews first attended college at Washburn University before she found her interest in journalism and transferred to the University of Kansas. When she felt like she needed a break from the hectic life of a college town, she would go out to the site overlooking the lake, near the present-day Rock Creek Marina.

“I went back there a lot and would just think, think about what would happen,” Andrews said.

Years later, in 1992, Andrews had just moved to Wichita with her then-husband and a newborn son, and she was working at a magazine. One day, her phone rang. It was her dad, calling to say he had read an article in the newspaper about a woman who wrote a short story about the fire at the farm. This woman wanted to work with someone else to expand the story into something longer.

Andrews wanted to learn more, and she connected with the writer, McCabe, who lived in a house near where Andrews’ family lived. She learned quickly that McCabe knew her stuff.

“(McCabe) knew the story as well or maybe even better than we did,” Andrews said.

Much of that knowledge stemmed from McCabe’s conversations and notes she took from talking to locals around Perry Lake, including a man named Nate Isaac who knew great-aunt Jennie, Andrews said.

As well as being writing partners and sharing notes on the subject, Andrews said she and McCabe grew close, and Andrews would often drive up to Perry Lake with her son to work on the project.

“I’d go there to write; she’d take care of my son,” Andrews said.

Six years into their partnership, Andrews said, McCabe died of cancer. But Andrews was determined to keep the project going. She said she used many of McCabe’s suggestions in the final version, including some of the main structure and McCabe’s copious notes.

Between those, McCabe’s sources and Andrews’ father’s invaluable family records, Andrews now had a good foundation to start the book, but she had to “put it away” for many years as she went back to working full-time. She was able to start again near the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Andrews knew how to write magazine articles, but she said writing a book was a “whole other thing” that often felt “unwieldy” and all-consuming. Sometimes she would work during vacations. When she was able to publish the book this year after over 30 years of work, she felt proud to finish it and make good on her promise to McCabe.

Soon, Andrews and McCabe will get some special recognition for their work. On Oct. 5, Andrews said she’ll be in Oskaloosa to give a talk about the book and the fire, and she and McCabe will also be honored by Jefferson County because of the setting of her novel. Andrews said she is glad that McCabe will be recognized, too.

After Andrews took the mantle of being the family “keeper” from her dad by exploring the family’s history and genealogy, it has felt fulfilling to have the story published. Andrews said her father often said, “To know where you’re going, you got to know where you came from.” She thinks that this book is an encapsulation of that and can help others learn about the importance of the past, as well as the importance of looking into your own past.

“To understand the history and what (your ancestors) went through, it helps you understand yourself better. We carry it — whether it’s sorrow or grief or joy — those things are a part of us,” Andrews said.

Andrews’ and McCabe’s book can be purchased online at lulu.com.