The police have no interest in spying on you; camera registration and integration are voluntary and for crime response only

Department hopes to quell fears with presentation Tuesday

photo by: Adobe Stock Photos

When Nicholas Beaver murdered a man last year in downtown Lawrence, then fled across town on his bike, he was likely unaware of just how many cameras had recorded his actions.

Some of those cameras — like the one that captured three ear-splitting gunshots and Beaver’s victim collapsing on the sidewalk — were owned by private businesses. Another was owned by the Lawrence Public Library, and another — the one that captured Beaver escaping through a residential neighborhood where he would ditch his gun, his bike and incriminating clothing — was owned by a homeowner.

All of that footage, plus video from traffic cameras owned by the city, played a role in securing a first-degree murder conviction against Beaver, who otherwise might have prevailed on his claim that he shot Vincent Lee Walker in self-defense.

“Go back and watch the videos!” then-Deputy District Attorney David Greenwald passionately urged jurors in his closing argument at Beaver’s trial earlier this summer. They did so — and returned about two hours later with a guilty verdict.

Though the video footage was not the only evidence against Beaver, Greenwald knows that it was “crucial.”

“As important as eyewitness testimony is, everybody views the world in different ways,” he told the Journal-World. “When you have a video that has, for lack of a better phrase, an objective truth to it, where you can see what happened … it takes a lot of questions out of the jurors’ minds.”

Lawrence Police Chief Rich Lockhart described the footage as invaluable in quickly solving the downtown murder, and he hopes a new community program — one that uses technology to streamline that type of “objective” evidence gathering — can lead to even quicker investigations, enhancing public safety and producing numerous efficiencies in police work.

photo by: Kim Callahan

Police investigate after a fatal shooting on Vermont Street on Wednesday, March 6, 2024. Lawrence Police Chief Rich Lockhart is at center in white shirt.

The new program

Earlier this summer Lockhart’s department announced that it had teamed up with the public safety company Axon to launch Fusus Connect Lawrence, a technology platform that allows residents and businesses to register their private security cameras — for homeowners, think doorbell cameras — with police.

Registering a camera, which is entirely voluntary, simply means that police know it’s there, Sgt. Drew Fennelly said. It doesn’t mean that police have any access to the camera or permission to see what it has recorded. All of that is under the homeowner’s complete control.

What it does mean is that the police would know that cameras exist at certain locations. In the Beaver case, officers had to canvass the area of the crime scene, determine where cameras were by looking around and then make personal contact with camera owners to request footage — a process that can be time-consuming and pull officers from other necessary facets of the investigation, such as speaking with witnesses and collecting other types of evidence.

Traditional canvassing of crime scenes doesn’t go away with prior knowledge of camera locations, Fennelly said, but the canvass can happen much more quickly. With Fusus Connect, officers can consult a map of registered cameras and simply request that a homeowner, for example, upload relevant footage via a link, if they so choose.

Lockhart and Fennelly both observed that most people who own security cameras do so because they are concerned about safety — and they are usually only too happy to share footage that they believe might be helpful in solving a crime.

Registration of a camera location is free, and residents can learn more about the program at connectlawrence.org.

Another component of the Fusus system, one meant for entities like businesses, is not free but allows what is known as camera “integration.” Costing anywhere from $350 to thousands of dollars a year and requiring special hardware and a Fusus subscription, integration allows camera owners — if they so choose — to turn on a feed to share video with police in real time.

The department doesn’t see any benefit in private home cameras having live-stream integration and will not allow it, per draft language in the department’s video policy.

An example of business camera integration would be if a convenience store were being robbed, a camera owner could provide video access to police of what is happening in the moment. One benefit of this, Fennelly said, is that police responding to the scene would know in advance what they might encounter when they arrive. Is one suspect present? Multiple suspects? Are they armed? Is an ambulance needed?

“It’s about preparedness,” Lockhart said, and about community partnership in solving crime quickly.

But is it surveillance?

No, Lockhart said. It’s decidedly not surveillance. The program is completely voluntary and under the control of camera owners at all times. Additionally, he said, even if the system allowed for it, police simply have no desire or time to “spy” on residents, on the off chance that they will do something illegal.

Police don’t even monitor the 100-plus city-owned traffic cameras or 330 city-building cameras unless they have been alerted to look for something specific related to an investigation, Fennelly said; monitoring the cameras in “anticipatory mode” would be a poor use of officers and resources.

The Fusus platform is about responding, not deterrence, he said.

Lockhart and Fennelly both appreciate that residents have valid questions and concerns whenever the words “camera” and “police” occur in the same sentence. But the references Fennelly has seen on social media and elsewhere to “Big Brother is Watching You” from George Orwell’s dystopian novel “1984” are largely the result of misinformation, which can spread like wildfire on social media.

In view of that, Fennelly said, the police department could have done more to anticipate concerns and allay worries ahead of the program’s rollout, including education about the many safeguards that are already in place when it comes to police and cameras.

Some of these safeguards, he said, are annual audits of the public video system, detailed user logs, training and access requirements, and a rule against sharing data with outside agencies without a formal written request.

Axon, he said, will not provide information to any third party, such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, “without our permission.” And the department, in any case, is required to give public notification if ICE requests its assistance with a warrant.

City Commission has approved

The Lawrence City Commission has already OK’d the Fusus platform. Commissioners, in their consent agenda, approved a contract extension last November with Axon, the provider of the police department’s body cameras, in-car video, Tasers and digital evidence management. The $3.2 million contract, which runs through 2029, bundled in the Fusus platform, which accounts for $270,816 of the contract price, or about $54,000 annually.

It’s not clear if commissioners were entirely aware of what all they were approving, as previously they considered separate contracts, not a bundled contract. The five-year bundled contract reportedly helped the city save an estimated 8% increase in costs for Axon services over a year-to-year contract.

When the police department announced the Fusus registration and integration program earlier this summer, some residents, including a group called the Lawrence Transparency Project, were taken by surprise and demanded a program pause until more public discussion could take place.

At the commission’s Aug. 5 meeting, about 20 people spoke during the general public comment period protesting the implementation of the Fusus program, saying it didn’t get an appropriate hearing by commissioners and was not fully understood when the commission approved the contract.

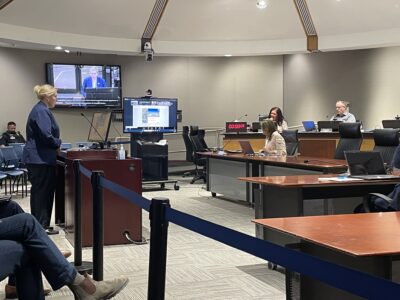

Fennelly said he had met privately with some of those residents to discuss their concerns, but he is also planning to make a public presentation during a work session at Tuesday’s commission meeting, and he welcomes public feedback.

photo by: Kim Callahan/Journal-World

Lawrence Police Department headquarters, 5100 Overland Drive, is pictured June 28, 2022.

Real Time Operations Center

At that meeting, Fennelly will discuss applications of the Fusus software but also the police department’s larger goal of one day implementing a Real Time Operations Center, or RTOC, which is already a reality — and a success, he said — in cities like Tulsa, Oklahoma; Irving, Texas; and Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

The Fusus program would be an important component in an RTOC, which is a centralized data hub dedicated to responding to criminal activity in real time. Right now, Fennelly performs that function on top of his other duties, sometimes with the help of an officer who is on desk duty due to an injury. The work largely consists of viewing live video when police are alerted to a call and getting immediate eyes on a situation — say, a suspect assaulting someone at a downtown store and fleeing.

Fennelly, at police headquarters, can see the incident unfolding through various public cameras and alert nearby officers, whom he can see on a map, to where the suspect appears to be headed, whether he is visibly armed, whether he gets in a vehicle and other critical information — all details that frequently would not be known to police, possibly imperiling their safety, until they arrived at the scene and started interviewing witnesses.

Having a couple of officers dedicated to such work in a full-time RTOC would take full advantage of the technological tools and efficiencies now available in crime-fighting, Fennelly said.

Such a hub would be a significant expense, though — “anywhere between $1.6 million and $2.3 million to fully do it,” he said.

That money is not available right now, amid funding cuts and staffing shortages, but the department is hoping that in future budget discussions the benefits will be seen to outweigh the costs.

City commissioners will hear information related to the Fusus platform and the RTOC goal at their Tuesday meeting beginning at 5:45 p.m. at City Hall, 6 E. Sixth St.