Leader of Lawrence’s Homeless Solutions Division feels like ‘nobody wants to hear the good news’

photo by: Josie Heimsoth/Journal-World

Misty Bosch-Hastings speaks at an Integrated Outreach Event on Wednesday, May 14, 2025.

Living outside in an unsanctioned homeless camp, Misty Bosch-Hastings says, is “horrific.”

In two years as director of Lawrence’s Homeless Solutions Division, she’s seen enough human trafficking, violence, substance abuse and death in encampments to know that.

“It’s horrific. It’s horrific,” she repeats. “It’s not just a good old time, you know, all just hanging out, just loving each other, living off the land. Bullshit. That’s not it. It’s illness, it’s addiction,” and sometimes it’s much worse.

That’s why she and her colleagues will work with clients for months or even years in hopes of getting them into shelter.

And it’s why she’s so frustrated when she hears people say the city is treating the homeless poorly, or that they have nowhere to go.

She heard that refrain on social media when law enforcement cleared an unsanctioned camp near the Kansas Turnpike on Feb. 4. The night before that camp was cleared, Feb. 3, a crowd of people showed up at City Hall to speak to the Lawrence City Commission – some criticizing the city’s approach to providing services, others claiming they had been banned from the Lawrence Community Shelter and had no alternatives.

(The Kansas Highway Patrol confirmed to the Journal-World that it assisted Douglas County and the Kansas Department of Transportation in clearing the camp; the City of Lawrence was not involved.)

Bosch-Hastings knew people in that camp, she said. She and her team had offered them resources many times – and they turned them down.

“For the few individuals that were in the camp at the Kansas Turnpike, those are folks that we have worked with for years and housed within the last year,” she said. “Some of them left housing. One of them has turned down two housing vouchers.”

“It is frustrating,” she continued, “to have that painted in a light that’s, ‘Nobody knows their next step, nobody knows where to go.’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, they do. Yeah, they do.'”

As the city and county strategic plan to end chronic homelessness, A Place for Everyone, is entering its third year, Bosch-Hastings and other local officials who work with the homeless say what was once a crisis has dramatically improved. City and county commissioners heard reports on the progress this month, and numbers that looked dire a couple of years ago have gone way down.

Take the point-in-time count, an annual tally of unsheltered and sheltered homeless individuals in a community on a single night in January. Just from 2024 to 2025, the number of unsheltered homeless people in the county’s point-in-time count dropped by 63%, from 142 to 52.

Or take weather-related deaths. Last winter, there were zero of them for the first time in over two decades.

“If you go back a couple of years to where we are today, it’s a big difference,” Mayor Brad Finkeldei said Tuesday after hearing the report.

But Bosch-Hastings, who was hired as the city’s homeless programs coordinator in the summer of 2023 and was named to her current role in February 2024, thinks many people in Lawrence don’t have that same appreciation. She said she feels like “nobody wants to hear the good news” from her and her team.

“When I got to town and the city-sanctioned camp was open, just the amount of horrific things that were happening there, up to murders …” she said, referring to Camp New Beginnings, the “support site” behind Johnny’s Tavern that closed in 2024. “I don’t think they knew the volume, the amount of people that were sleeping outside, and it was over 200 when I got here.”

Her estimate of how many are sleeping outside in Douglas County right now? “I would say less than 20.”

There are still homeless people in downtown Lawrence, she said. But these are often people who are staying in the Lawrence Community Shelter’s night-by-night program and take the bus to go downtown during the day. The problem of homelessness hasn’t gone away, she said, but the problem of people sleeping outside has greatly improved.

“I don’t think that people knew just how bad things were,” she said.

photo by: Kim Callahan/Journal-World

A campsite at Burcham Park Wednesday, Sept. 17, 2025.

‘I’m not ignorant’

She remembers a case that showed just how bad encampments could be.

It involved a woman who was severely intellectually and developmentally disabled. A man had brought her to Bosch-Hastings in hopes of getting help.

“He had some struggles of his own,” she said, “but he had it together enough to say, ‘Would you please help her? Because she continues to get raped.’

“It just blew my mind and opened my eyes to what’s really happening in these encampments,” Bosch-Hastings said.

When there were large homeless encampments within the city limits, the Journal-World reported on more than half a dozen deaths and a number of violent incidents involving unhoused people.

Some of the deaths were drug overdoses or were related to cold weather. Others were homicides, such as that of Crystal White, who was found in her tent in February 2024 after having been stabbed to death.

Bosch-Hastings is convinced that “heartbreaking” situations are still happening among people who camp.

She mentioned the recent case of Brandon Eugene Snow.

Snow was accused in 2023 of chasing a couple with an ax near Camp New Beginnings. A jury acquitted him of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon in August 2025.

Then, just this month, Snow was arrested again and charged with aggravated assault and domestic battery. Police said a worker at the Lawrence Public Library reported a man hitting a woman, pulling her hair and then leaving. They said they later found the man chasing the woman down the street with a baseball bat, arrested him, and identified him as Snow.

Snow was at the encampment at the turnpike, Bosch-Hastings said. The alleged assault and domestic battery were reported Feb. 4, the same day the camp was cleared.

What might have happened if the camp had been left alone, Bosch-Hastings wondered? Would a crime like that have taken place there? Would that woman “have survived or have received help?”

“We know about those things,” she said. “We see those women who are trafficked and physically abused. The brand new glasses that we got them on Friday? Boyfriend didn’t like them, so he broke them. And now she can’t see. That kind of stuff.

“It doesn’t get spoken about, and I know people don’t expect me to say that,” she said. “… I help the homeless, but I’m not ignorant.”

When people choose to live in encampments, she thinks, it’s often because they want to stay “out of sight.”

“These aren’t just wholesome, great people just trying to live off the land,” she said. “That’s not what happens out there.

“And it makes me sad that that’s the way it’s being framed, because I don’t want to encourage anybody to stay in an encampment.”

photo by: Kim Callahan/Journal-World

The Amtrak homeless camp is pictured early Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024.

Nonresidents still get help

Among the biggest misconceptions that bother Bosch-Hastings is the idea that her department only provides services to people who can prove they live in Douglas County.

“One thing that’s perceived really negatively is that (some people) say that we just deny services to people who are not from the area,” she said. “And that’s not true, either.”

In August 2024, the city began a policy that prioritizes serving people who are from Douglas County. From the start of the policy, the Homeless Solutions Division said it would still provide services to nonresidents, but it would only be short-term assistance and would be focused on helping them return to their communities of origin or other places where they have support.

At the City Commission’s meeting on Tuesday, Homeless Solutions Division staff summarized what kinds of help they can provide when a nonresident shows up looking for services. Some of the examples given at the meeting were helping someone get identification if that was their only barrier to stable housing and employment, connecting them to people in their community of origin who could help them, or referring them to service providers that don’t have a residency policy such as Bert Nash Community Mental Health Center or Heartland RADAC.

“They don’t get the full scope, they don’t get the full investment that the city and the community has made in this,” Bosch-Hastings told the Journal-World. But they aren’t ignored, either.

But what if you live in Douglas County and don’t have any documents that prove you’re a resident? Multiple public commenters at the meeting on Tuesday were concerned about that exact situation.

“I want you to imagine for one second that you were homeless tomorrow,” one commenter told the commission. “Are you carrying your utility bill with you? Is that the most pressing thing to grab?”

“You might say, in German, ‘Ihre Papiere, bitte’ – your papers, please,” said another.

After hearing these comments, Vice Mayor Mike Courtney asked what documents people actually had to provide to prove their residency. “Is it a utility bill, is it a lease?”

The answer: They might not have to provide any papers at all. In many cases, when a person can’t provide proof of residency, the team will verify on its own whether the person is from Douglas County.

The Homeless Solutions Division staff explained it to the commission like this: When someone comes to the Lawrence Community Shelter and can’t immediately prove residency, they get a three-day “respite period” during which they can gather the necessary information if they have it. If they still can’t, the shelter will contact the Homeless Solutions Division, and they will try to confirm the person’s residency through other sources of data.

So, instead of someone presenting a utility bill or a lease document, they might call utility companies and check whether the person was a customer, or call a past landlord and ask whether they had a lease. Only when the Homeless Solutions Division has exhausted all of its options will it tell the shelter that the person’s residency can’t be determined.

“We use anybody’s information, any record we can get our hands on,” Bosch-Hastings told the commission. “… We try to get creative. And if somebody’s lived here, there’s going to be a footprint somewhere. Nobody is saying you have to have a lease or utility bill.”

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

The Lawrence Community Shelter, 3655 E. 25th St., on Tuesday, Nov. 18, 2025.

Permanent bans?

Courtney had questions about more than just residency on Tuesday. He also wanted to know whether anyone had been permanently banned from the Lawrence Community Shelter.

Some of the people who spoke to the commission two weeks earlier, before the turnpike camp was cleared, did claim that the shelter had banned them indefinitely. On Tuesday, though, city staff told Courtney they didn’t believe anyone was permanently banned – but that came with some qualifications.

“Right here, at this moment, there is nobody that I’m aware of that is permanently banned from the shelter, in the sense that we can’t advocate for them to get back in the shelter,” Kelby Sanders, a member of the Homeless Response Team, told Courtney on Tuesday night.

Sanders said that “many times this is something that somebody believes has happened.” But other times, he said, there are sexual or violent incidents that have occurred, “and of course they’re not going to be able to return at that point. At that point, we discuss other options.”

At Tuesday’s meeting, one of the public commenters claimed to know that people had been banned or something similar. The commenter, Rowan Scheuring, self-identified as “somebody with experience as a direct service advocate at Lawrence Community Shelter.” Scheuring told the commission that “at least through to last month, there are several people who do have an indefinite loss of services from Lawrence Community Shelter.”

The shelter receives local government funding — $3.15 million from the city of Lawrence for 2026 — and its agreement with the city tasks it with providing emergency shelter, programming and meals for guests, among other services. To find out more about how the shelter handles behavioral issues at its facilities, including The Village of Pallet cabins on North Michigan Street, the Journal-World reached out to executive director James Chiselom and deputy director Kim Brabits via email earlier this week. The Journal-World asked them what the shelter’s procedure was for deciding to “exit” a guest; whether there are certain behaviors the shelter has zero tolerance for; and how many guests, if any, have been permanently banned, among other things.

As of Friday afternoon, nobody at the shelter had responded to the Journal-World’s inquiry.

The shelter does have lists of “guest expectations” on its website. For night-by-night guests, for instance, they include not making threats or hateful comments, “respect(ing) the right of others to feel safe,” surrendering weapons and alcohol upon entry and not bringing “substances or paraphernalia” onto the property. The latter can result in “possible exit from services,” but that’s the only specific consequence mentioned on that list.

Bosch-Hastings said she sometimes doubts people who say they’re permanently banned – not just that she doubts whether it’s true, but also whether they even believe it themselves.

“A lot of folks will say, ‘Oh, I’m banned from the shelter.’ Let me just say, in my 10 years of doing this across different cities, a lot of people say that because they don’t want to go to the shelter. They just don’t want to,” Bosch-Hastings said. “It’s just survival. It’s not the choice that they prefer, so they say that’s not an option.”

On the other hand, Bosch-Hastings said some people really can’t go to the shelter, and for them the team tries to come up with alternatives.

She gave the example of a man the team had worked with who had just gotten out of prison and who “could not go to the shelter because his crime was at the shelter, against shelter staff.”

This man did want to go to drug treatment – “it’s wild to me that people can come out (of prison) still heavily using,” Bosch-Hastings said – and the team worked toward getting him a placement in an Oxford House, a type of shared sober living residence.

Things didn’t work out for him, though, because he committed another crime. “He’s back in jail, and he’ll be back in prison,” Bosch-Hastings said.

photo by: Austin Hornbostel/Journal-World

Homeless Programs Coordinator Misty Bosch-Hastings speaks at the City of Lawrence and Lawrence Community Shelter’s “Welcoming Celebration” for The Village on Friday, Feb. 2, 2024. Lawrence Mayor Bart Littlejohn is at left.

‘Celebrate wins every day’

Many people the team meets have challenges that last a long time and don’t just go away when they start getting help.

The department and its partners in health care, emergency services and social services have a way to manage this, however. It’s a Monday morning meeting that they call “Familiar Faces” where they can collaborate on clients’ care. Agencies can refer a person with more complex challenges to the Familiar Faces group, and “whoever was referred that week, we could target for service,” Bosch-Hastings said.

“We talk about those people, like, ‘What are we going to do?'” she said. “We can call Adult Protective Services over and over again, and nothing really comes from that, unfortunately, so what we try to do then is figure out, how do we go from this person calling 911 44 times a month to not calling anymore or calling once a month?”

One such person was a man the team told the city and county commissions about. Bosch-Hastings said he was unsheltered for “a very long time” and was frequently calling for and utilizing emergency services.

In December, the commissions heard, he was finally housed. Since then, he had only called emergency services one time. And that time, Bosch-Hastings told the Journal-World, was a sensible use of services – a close friend of his had just died, and “he reached out for help instead of doing anything stupid.”

How often does Familiar Faces succeed? “I can only think of one person that we’re still struggling with,” Bosch-Hastings said.

Sometimes, the Familiar Faces group has to get creative to serve its clients. The man who was housed in December, for instance, had certain bills that the team was willing to cover, because “that was the investment that we were willing to make to keep that gentleman from going to the ER 44 times,” Bosch-Hastings said.

In the meantime, she said, they’re helping him get Social Security and other benefits.

“It’s just a small investment where we get those benefits rolling for him, and he’s doing great, and now he’s reaching out and trying to get his friends in there,” she said.

He isn’t the only one paying it forward. Bosch-Hastings remembered another person the city had housed, one she met at the homeless camp near the Amtrak station.

Not only has this person turned her life around, gotten sober and become a nursing student, she also works in the local homeless response now, and her partner is working with the drug and alcohol nonprofit Mirror Inc.

“They have years of sobriety, they’re doing amazing, and she’s helping with the Winter Emergency Shelter,” Bosch-Hastings said. “And there’s just so many stories of what these folks have gone on to do and be with the support that we’ve been able to give them.”

Something she and her team try to do is to “celebrate wins every day,” she said. “At the end of the day, whatever we’ve done, we celebrate the wins.”

And the city itself has won praise from other communities for how it’s cared for homeless residents.

Cities and counties elsewhere in the region have reached out to Lawrence for ideas on their own homeless programs. Bosch-Hastings mentioned a few: Columbia, Missouri; Wyandotte County; Hutchinson.

And she herself has been asked to speak at the National Alliance to End Homelessness leadership conference this year.

She said Lawrence should be proud to be a model for how to do homeless outreach and care right.

“There’s a lot for the community to be proud of,” she said. “They invested in this, and it worked.”

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

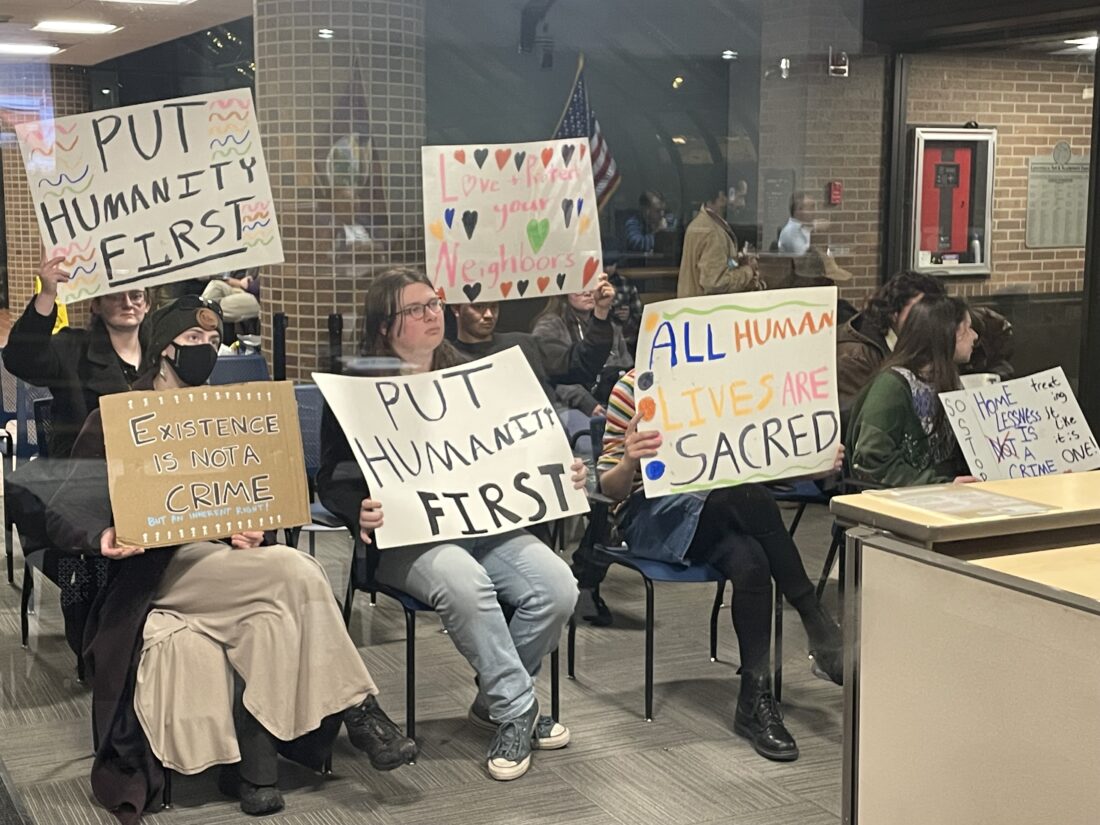

People hold signs outside of the Lawrence City Commission meeting room at City Hall on Feb. 3, 2026. They were there to protest the closure of a homeless camp near the Kansas Turnpike that the city was not involved with.

‘The silent majority’

So why has she heard so many critical, cynical and angry voices?

In December 2024, she posted on social media about the vitriol she’d experienced in the community while doing her work.

“Where else can you go to work and be verbally assaulted, bullied, screamed at while spit is flying in your face and it’s ok?” she posted then. “I can’t imagine anyone would be ok with this behavior if it was happening to you. Civil servant doesn’t mean deserving of abuse.”

She has a theory about why some people react so critically: “There’s certain folks who just dislike anything to do with government.”

“That’s been one of the biggest challenges of this position,” she said. “This position has never been hard because of a homeless person. It’s been hard because of the things that come along with working for the city, and how everybody has an opinion about how things should be done, and they think we’re not doing enough, or we’re doing too much.”

The city has been on the receiving end of both types of criticism.

In 2023, much of it was coming from business owners and neighborhood residents in places with large unsanctioned camps, like North Lawrence and East Lawrence. A group of business owners that year filed a lawsuit asking a judge to declare that the camps were public nuisances and to order them closed.

The suit was aimed not just at the unsanctioned camps in those neighborhoods, but also the city-sanctioned Camp New Beginnings behind Johnny’s. The plaintiffs spoke of a “vagrancy crisis” and called the camps “lawless zones that promote crime.” Johnny’s owner Rick Renfro said back then in a statement that he’d tried working with the city, but that “the city has failed our employees, customers and the homeless population in the management of the New Beginnings camp.”

More recently, different people have been saying the city’s homeless policies are too aggressive, or even “cruel.”

At the City Commission meeting before the turnpike camp was cleared, about an hour’s worth of speakers addressed the commission during its public comment period, at times emotionally. They criticized a variety of aspects of the city-county homeless response, including the residency policy and previous closures of camp sites on public land.

“They don’t get to choose where they live,” one commenter said, “because they keep getting kicked out of places where they set something up.” Another said: “It is nonsensical and cruel to have a policy which denies shelter to people who live here but just can’t show papers.”

Some of them also called the camp closures in Lawrence, which were preceded by months of notice and outreach to the homeless population, “sweeps” – a term Bosch-Hastings objects to.

“We don’t do sweeps,” she said. “We’ve managed to close encampments where people are just leaving. Nobody’s getting arrested.”

Many people just have gaps in their knowledge about the city’s homeless work, Bosch-Hastings thinks. Out of everyone in Lawrence, she estimated that “a little over half know about 10% of what we’re doing and what we’ve done.”

She’s confident that half of the community knows something, because of the sales tax referendum in 2024. That measure raised the city’s affordable housing sales tax from 0.05% to 0.10% in order to fund homeless services, and it passed with 53% of the vote – a little over half. She thinks people wouldn’t have voted to raise their own taxes if they didn’t think the city was doing a good job.

“I think there’s a lot of folks who don’t know the whole picture or don’t understand the whole picture,” she said. “But I do believe that the silent majority do know that there’s good work happening and are supportive of that work.”

And even if the public doesn’t always show its appreciation, she knows the people who have climbed out of homelessness certainly do.

“So many times I’ve heard from them, ‘I just didn’t know where to start. I just didn’t know how to end what I was doing,'” she said.

“Those stories, just all the successes that have happened and the lives that have changed, it’s significant.

“We just don’t talk about that.”