Lawrence police say new Fusus system can make their work more efficient; some members of the public want a pause

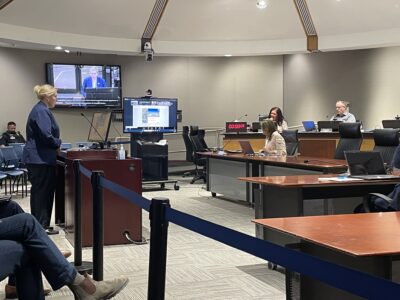

photo by: Sylas May

Sgt. Drew Fennelly addresses the Lawrence City Commission on Tuesday, Sept. 9, 2025. On the end of the front row of seats is Police Chief Rich Lockhart.

A call comes in for a disturbance in Centennial Park. Lawrence police are on their way, but what dispatchers haven’t been told – and officers therefore don’t know – is that the suspect is armed with a baseball bat.

“We don’t want that to become an escalating confrontation,” Sgt. Drew Fennelly told the Lawrence City Commission on Tuesday night.

And it didn’t – in part because police were watching cameras remotely and could tell the officers the bat was there. They could approach more carefully and deescalate the situation.

“We were able to have a more peaceful resolution to this incident,” Fennelly said. “Nobody was arrested, everybody walked away.”

This was one of several incidents police walked Lawrence city commissioners through on Tuesday night as they discussed “simulations” of a system it wants to one day implement on a wider scale — what it calls a Real-Time Operations Center.

The department has been using cameras in new ways, Fennelly and Police Chief Rich Lockhart said, to track and respond to incidents more efficiently. That includes a new system called Fusus that will make it easier for police to aggregate footage from a variety of sources, and a voluntary camera registration program that will let police know where private security cameras are but won’t grant access to them.

At the same time, dozens of public commenters urged the commission to press pause on Fusus and its implementation to allow for more public input – as one of them said, “so we can work forward in good faith.”

Fusus systems

Tuesday’s presentation, which was for informational purposes only, focused largely on Fusus, which the commission actually approved nearly a year ago.

Last November, commissioners in their consent agenda approved a contract extension with Axon, the provider of the police department’s body cameras, in-car video, Tasers and digital evidence management. The $3.2 million contract, which runs through 2029, bundled in the Fusus platform, which accounts for $270,816 of the contract price, or about $54,000 annually.

Essentially, LPD says that Fusus is an aggregating tool — something that brings together a variety of resources the department already has, such as cameras and license plate readers.

Currently, the city’s many cameras operate on different systems – for instance, the traffic cameras and the cameras in city buildings are on different servers, and Fennelly said that costs officers time when monitoring high-pressure situations.

“We have to log out of that system and use a different login to log into the city system,” Fennelly said.

It might only be one or two minutes, but that can be a long time when responding to a call, and “we lose a lot of information,” Fennelly said.

Fusus, Fennelly said, was more like a “single pane of glass.” It generates a map that officers can use to monitor all of their resources in one interface.

Currently, Fusus incorporates the city’s 112 traffic cameras, police vehicle cameras and officers’ Axon body-worn cameras, Fennelly said. It also has a variety of tools that officers can use to keep track of information on the map.

There are a couple of things that police wanted to make clear about what Fusus is not.

Fusus is not intended to be used for surveillance, Fennelly and Lockhart said. It also is not a facial recognition technology, they said, and Axon and the police department both had policies prohibiting the use of such technology.

While Axon does not do facial recognition, it does include a suite of AI tools, but Fennelly cautioned that these are extremely limited.

“It’s very limited in what we’re able to search on this,” he said. One example he showed was a group of search results for blue cars. It showed some blue vehicles, but also some in gray or beige.

“You can see three of the six detections that are not blue cars,” Fennelly said.

The AI also has a people search that includes just a few options: whether a person has a bag or backpack, whether the person has a hat on, the color of the person’s clothing, and “gender.” Fennelly said he did not know how the algorithm determined the gender of a person seen on the cameras.

Fennelly noted that some of the city’s cameras were 10 years old or more, and that made the AI tools “a shot in the dark.”

“At the end of the day,” Fennelly said, if the cameras don’t improve, “it’s still garbage in, garbage out.”

The tools can be disabled if a department doesn’t want to use them, and if Axon eventually decides to allow facial recognition and LPD decides it doesn’t want to use it, Fennelly said that could be disabled too.

Who owns the cameras?

One big question Lawrence police tried to address on Tuesday was who owned the cameras and who could access them.

The department stressed that the city’s own cameras would continue to be city-owned, and would not be owned by Axon or any other company. Lockhart said the department had studied Columbia, Mo.’s systems, and that Columbia used a platform developed by the company Flock Safety. The difference between Flock’s system and Fusus, Lockhart said, was that Flock owns the cameras, drones and license plate readers associated with that system.

With Fusus, “No one can access our system without permission from us,” Lockhart said.

Other concerns have to do with a camera registry for private residences and businesses. As the Journal-World has reported, these registries are voluntary, and there are limits on how much access police have — both in policy and in the actual hardware.

Signing up for the registry doesn’t mean that a camera owner is required to share footage with the police. When an incident takes place in an area where cameras are registered, Fusus can send an email to the camera owners encouraging them to review their video and submit clips, but whether the camera owner does so is entirely voluntary.

Fennelly mentioned Fusus’ partnership with the Ring doorbell camera brand. He reiterated that the partnership was just about “creating a separate camera registry,” where Ring would contact its customers within that area “on behalf of the Lawrence Police Department.”

“It’s just Ring letting them know” that there was a crime in your area, he said, and “if you’d like to submit footage you can do so.”

At businesses, owners can purchase a special server called a “Core” that will allow them to stream video live to police, but this won’t be allowed under LPD’s policy with cameras at private residences. Even for businesses with a “Core,” Fennelly said that the idea was not to provide constant surveillance of businesses.

“The purpose of this system is not to provide security monitoring” for businesses, Fennelly said.

A Real-Time Operations Center

Even though the funds aren’t available yet for a Real-Time Operations Center, the police department’s attempts to simulate one with its current tools have been making the department’s operations more efficient, Fennelly and Lockhart said.

In addition to the Centennial Park call, Fennelly said these technologies had helped track fleeing suspects with traffic or downtown cameras, and that they even helped find a quadruple homicide suspect from Ohio whose car was detected in Lawrence in 2022.

“What we have seen is that providing this information to responding officers is incredibly beneficial,” Fennelly said.

Fennelly said that even medical calls could be made more efficient by this system. He mentioned a call where cameras showed it was a false alarm and there was no patient. That meant responders could be more quickly reallocated to other calls.

Pushback and police’s response

When the police department announced the Fusus registration and integration program earlier this summer, some residents, including a group called the Lawrence Transparency Project, were taken by surprise and demanded a program pause until more public discussion could take place.

More than a dozen people called for a pause at Tuesday’s meeting, too. Some of the meeting attendees carried signs; others wore masks, sunglasses and other face coverings.

Some speakers were opposed to the idea of camera use in general and to the potential for privacy violations. Lockhart wanted to allay these concerns, and he pointed to the department’s record with body cameras and other cameras for years.

“We’ve been responsibly utilizing city traffic cameras and building cameras since 2008, and our license plate readers,” he said.

Other commenters said they weren’t opposed to cameras, but were more opposed to how the rollout had been handled. One said police had taken the time to meet with stakeholders over the past few weeks and that more discussion needed to happen.

“I will admit readily that cameras do solve crimes,” the speaker said. “I think that the problem is that this conversation should have happened a long time ago. This conversation is the start.”

One of the public commenters who spoke identified himself as a police officer, and he said he wanted the public to know that “We’re not watching you.”

“Ultimately,” he said, he was “just wanting it to be known that we are trying our best to do what is best for our community.”

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

A sign across the street from Lawrence City Hall, 6 E. Sixth St., on Sept. 9, 2025. The sign alerts the public to the cameras in use in the downtown area.