Connecticut Street sidewalk project is producing a mix of concrete and brick — and a mix of emotions

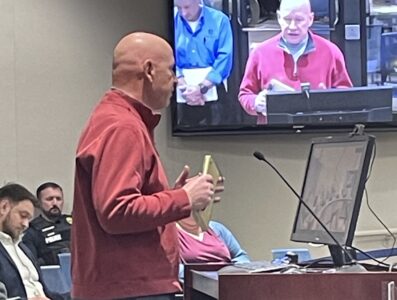

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

Barry Shalinsky, past president of the East Lawrence Neighborhood Association, points down Connecticut Street in the direction of concrete work on Friday, Nov. 14, 2025.

“One property at a time” is how East Lawrence was built, Barry Shalinsky says on a walk through the neighborhood Friday morning, and its patchwork of sidewalks reflects that.

“If you walk down these brick sidewalks, you see there’s like 20 different kinds of bricks and 20 different patterns that people put them in,” says Shalinsky, the past president of the East Lawrence Neighborhood Association. “And it was all very organic.”

But the walk stops at a tarp laid across the sidewalk in the 900 block of Connecticut Street. Underneath is new concrete, and if you want to keep going, you have to walk on the lawns, past pallets of dusty old bricks wrapped in plastic.

This is how the sidewalk on Connecticut is being rebuilt — also one property at a time, with property owners having to choose whether to use concrete or brick.

The intent of the project is to bring the walkway into compliance with the city’s accessibility standards. Evan Korynta, the ADA compliance administrator with the city’s Municipal Services and Operations, told the Journal-World that the work will span from Ninth Street to 12th Street, including alley connections, and is slated to be done by February 2026.

Korynta said 78 properties are in the project area, and they featured “both brick and concrete sidewalks in varying conditions.” The city’s Brick Streets and Sidewalks Policy, which was approved in October 2024, allowed property owners to choose which material to replace their old sidewalks with.

Fifteen chose brick, Korynta said, and 63 chose concrete.

But for Shalinsky, the question is what their reasons were and whether they had a meaningful choice at all.

“People chose concrete,” Shalinsky said, then paused for a few seconds. “But why?”

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

A gap in between two sections of new concrete sidewalks is pictured Friday, Nov. 14, 2025, on Connecticut Street.

How the policy works

Until the policy was developed, Korynta said, the city wasn’t able to do any major repair or replacement projects in this corridor. He gave some more details on how the policy works in an email to the Journal-World this week.

Kansas statute requires that property owners maintain the public sidewalks on their properties, but Korynta said the city gives people some help with paying for the repairs. For owner-occupied properties that meet certain income guidelines, the city will pay 100% of the repair costs for concrete sidewalks, and the city also provides assistance for properties with sidewalks on more than one side, such as corner lots.

In some parts of the city, property owners are given an additional option, Korynta said: whether to fix their sidewalks using brick or concrete. The city has a map of areas where sidewalks can be fixed using brick. It spans many historic areas of the city, including all of the downtown area; most of East Lawrence; and parts of the Oread Neighborhood, Old West Lawrence and the Pinkney Neighborhood.

The wrinkle, however, is that even with the city’s “cost-partnering” measures, people who want brick have to pay extra.

“Property owners who opt for brick are responsible for any additional costs beyond those associated with concrete,” Korynta said.

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

Workers load bricks onto a pallet in East Lawrence on Friday, Nov. 14, 2025. The sidewalk here is going to be replaced in concrete.

Neighborhood association’s concerns

For some property owners in East Lawrence, one question was just how much additional cost there would be.

Shalinsky – on behalf of the board of ELNA, of which he was president at the time – wrote a letter to the Lawrence City Commission about that in September, before the commission was slated to vote on a $556,000 contract for the project. He urged the commission to “hit the pause button,” because the neighborhood association had heard from some property owners that the city had “very strongly encouraged” them to go with concrete instead of brick.

“It was represented to property owners that brick could be significantly more expensive than concrete,” the letter read.

Specifically, Shalinsky’s letter cited the city engineer’s estimate for the costs of concrete and brick, and compared it to the actual bid from the construction company. The city had estimated that the concrete sidewalk restoration would cost $80 per square yard, while brick would be $250 per square yard. But the bid from the company had $100 per square yard for concrete and $150 per square yard for brick.

“The reality is that concrete was chosen for many,” the letter read. “Low-income residents needing cost sharing assistance were automatically defaulted to concrete. Property owners who did not affirmatively make a choice were automatically defaulted to concrete.”

The Journal-World asked Korynta about the communications with neighbors in advance of the project. He did say that property owners were told that unless they specified a preference, their existing sidewalks would be replaced using concrete.

But he also said that property owners had months of notice to make a decision.

The city first notified property owners of the project in October 2024, Korynta said, and then in February and March of 2025 they were sent letters that explained the process and laid out their options. Korynta said property owners were then given 60 days to notify the city of their material choice.

“They had the option to submit their material selection through an online portal, contact me directly via phone or email, or schedule an onsite meeting with staff to discuss processes, financial assistance, and options, which many property owners did,” Korynta said.

Korynta said city staff didn’t encourage people to choose one material over the other. In his email, he said that “City staff have no preference regarding the material selection, provided that it complies with the city’s accessibility sidewalk requirements.”

Even after the City Commission had approved the contract, Korynta said, property owners were given the chance to change their minds. They were sent a letter that said the prices of brick were lower than initially anticipated, and they were given two weeks to switch if they wanted to.

Shalinsky, however, said that two weeks was “not very long” for people to change their decisions. “It was something, but not much,” he said.

He also said that giving people a choice might not mean much if they didn’t know all of their options. For instance, people can hire a company other than the one the city uses, or even do the work themselves, to bring their sidewalks into compliance, according to the city’s sidewalk policy.

“Yes, everyone has the option of doing their own,” Shalinsky said. “But they don’t know where to go to get help, which means if they want to do it, they’re stuck with the city contractor.”

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

The gap between a new concrete sidewalk and an old brick one is shown on Friday, Nov. 14, 2025, on Connecticut Street.

Will the sidewalks last?

That reminds Shalinsky of another brick project that city contractors undertook during the reconstruction of East Ninth Street.

In that project, which began in 2018, the city unearthed thousands of historic bricks from beneath the asphalt and used some of them to rebuild sidewalks and intersections along Ninth.

As Shalinsky remembers it, “the city hired a contractor and said, ‘Put this in brick.’ But they did not provide any specs. They just said, ‘Do it.'”

Walking along Ninth, Shalinsky points out places where there are a lot of gaps and uneven spacing. He said that the best practices for constructing brick sidewalks involve creating a border of bricks laid on their sides to hold the other bricks in place; these are called “soldier bricks.”

“They’re sort of an anchor, and stuff can’t just spread apart,” he said. “… It’s best practice, and they didn’t do that.”

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

Uneven bricks are pictured on Ninth Street in East Lawrence on Friday, Nov. 14, 2025.

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

A row of “soldier bricks” on the edge of this sidewalk helps keep the other bricks in line in East Lawrence on Friday, Nov. 14, 2025.

When the city started talking about redoing the sidewalks along Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York streets, Shalinsky said ELNA suggested a sort of test run first – fixing the sidewalks that were part of the Ninth Street reconstruction.

“Our contention was, we have years and years under this program of replacing concrete sidewalks, we have a pretty good baseline of what it takes and what it costs, but we don’t have experience with brick,” Shalinsky said. “Rather than do three blocks of brick, why don’t we first do a pilot project and redo this brick that was obviously not done properly, get a baseline for what does it cost to do it, let it sit for a year or so and make sure that our new specs and protocols really work and that it holds up properly?”

That would also provide the opportunity for more local contractors to be trained in how to install brick sidewalks properly, Shalinsky said, “so that the homeowners can have an option and have people they can contact to do their brick sidewalks.”

“And then we roll it out,” he said.

The city didn’t go that route, though, and Shalinsky is concerned that the homeowners who chose brick could get a sidewalk in front of their houses that won’t last, like the parts of East Ninth Street without soldier bricks.

Even the quality of the concrete work is concerning for Shalinsky and others in the neighborhood. He said he’s personally seen things and heard reports from neighbors that worry him.

On one property’s concrete sidewalk, Shalinsky said, the owner observed that “there was no base layer of rock; there was no rebar. They were basically just pouring concrete on dirt and finishing off the top of it and that was it.”

The work done by the contractors is under warranty – the city’s program provides a two-year warranty for sidewalk repairs and replacements. But Shalinsky thinks that on the scale of time that a sidewalk should last, the warranty offered isn’t enough protection.

“Here we are doing three blocks with concrete with a two-year guarantee, and we convinced all these people to do it because it was cheaper?” he said. “… Those bricks have been there for 120 years.”

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

New concrete is covered with a tarp in East Lawrence on Friday, Nov. 14, 2025.

Costs and benefits

For Paula Schumacher, the fact that concrete was cheaper was the big reason to switch.

Schumacher, who said work began on the sidewalk on her property last week, told the Journal-World that it would have been about $1,000 more to redo her sidewalk in brick.

“I think it would be a consideration for anybody,” she said. “I mean, a thousand dollars. That’s a lot of pizzas, or a couple of months rent (if you’re a tenant).”

When the work started, though, she had some concerns that she shared with Shalinsky. That report of concrete being poured on dirt was from her, and though she said it looked like the dirt had been tamped down with machinery first, “that concerned me.”

“Every DIY show says that you’re supposed to put down gravel and you’re supposed to put down rebar or something to strengthen it,” Schumacher said.

So she asked some people involved in city government – someone who had been on an advisory board that had helped draft the sidewalk requirements, and City Commissioner Lisa Larsen, whom she said she knew personally. She said both confirmed for her that sidewalks don’t have to have those additional components unless they’re part of a driveway.

Schumacher wasn’t sure how the sidewalk would hold up over the long term. She said she wondered whether it would have cost less over the long run to go with brick, or to do more research and hire a contractor herself for the work.

“If and/or when the concrete fails, given time and entropy, will the city be coming back and asking me for $2,000 again?” she said.

But she didn’t feel like she was being pressured by the city to select one option or the other. She said the letters she received about the project were straightforward and didn’t take a side.

However, she also said that’s not the impression that everyone got. One of her neighbors had originally chosen a brick sidewalk but later switched his choice to concrete. She said he originally had the impression that because of historic preservation guidelines, he had to use brick.

“He acted as though somebody had really pushed on him for brick,” she said. “But I didn’t have that experience at all.”

Despite her doubts about the concrete work, Schumacher wouldn’t say that she has buyer’s remorse. She’ll have to see how well the concrete actually holds up before she can judge.

What she’s focusing on now is the upside of having new sidewalks of any kind in East Lawrence. She said that the new work “looks really nice,” and that when she walks in the neighborhood now, many of the sidewalks are “in really bad shape.”

“You know, at least for the next two years, we’ll have really nice sidewalks. They won’t be overgrown and they won’t be all cracked,” she said.

“So I’m definitely happy with that.”

Accessibility, affordability and history

The city’s sidewalk policy is intended to “ensure accessibility for individuals of all ages and abilities,” Korynta told the Journal-World, and for him that’s a personal issue.

As the Journal-World reported last year, Korynta was diagnosed with a rare cancer in 2007 and had to have his left leg, hip and the left side of his pelvis amputated after unsuccessful chemotherapy treatments. Korynta has used a left leg prosthetic and a wheelchair since then, and quickly learned that people who have disabilities weren’t well served by much of the city’s infrastructure.

He told the Journal-World then that “good, accessible, safe infrastructure” is something that the city really needs to focus on. And Shalinsky, who worked in the field of disability rights for 25 years, agrees wholeheartedly.

“I’m the last person in the world to say that we should not have safe sidewalks, or that people with wheelchairs should not have accessibility,” Shalinsky said. And he noted that “you can do brick in a way that they will last and are accessible.”

But Shalinsky also thinks that there are different values in conflict here – such as the idea of equity, which can mean many different things.

“Does ‘equity’ mean if you are in a wheelchair, you should have the same accessibility to use a public sidewalk as somebody who uses their feet?” Shalinsky said. “OK, you can say that’s what equity means.”

But it’s also an equity problem, he said, if your family has been in East Lawrence for many years, “you’re living on a fixed income, but you inherited (your home) and you grew up with those bricks, but you can’t afford this program.”

In that situation, he said, the message seems to be “yeah, we’ll fix your sidewalks, but we’re going to take your bricks away.”

Many bricks will in fact be taken away, but some of them will get new life elsewhere. Korynta said that the bricks still in usable condition would be used in the new sidewalks for those property owners who opted for brick, and if there are any left over, he said, they’ll be put into storage for now and could be used in future brick sidewalk projects.

But even if some of the bricks are repurposed, Shalinsky thinks that part of his neighborhood’s identity will be lost.

“It’s disappointing that we have all this rhetoric about ‘welcoming neighborhoods,’ ‘unmistakable identity,’ and you take a historic streetscape in one of the original neighborhoods in town – that is defined largely by brick sidewalks, stone curbs, hitching posts and buildings from the 1890s and earlier,” Shalinsky said. “And little by little, through the zoning codes and through the brick policies and whatever, just destroy that history and replace it with concrete that has a two-year guarantee.”

“You know, these new sidewalks, these new houses,” he went on, “none of this stuff they’re building is going to be here a hundred years from now like this stuff was 100 years ago.

“And it’s just sad.”

photo by: Sylas May/Journal-World

Barry Shalinsky, past president of the East Lawrence Neighborhood Association, walks past a construction site in East Lawrence on Friday, Nov. 14, 2025.