Once, it could be musty, earthy and weird, but now Clinton Lake plant’s water is now officially the best-tasting in the state

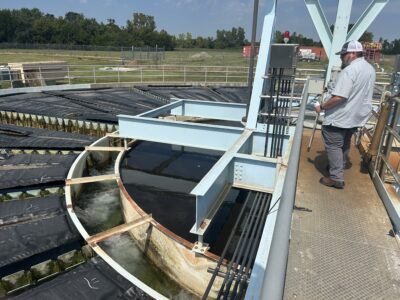

photo by: Bremen Keasey

Steven Craig, a Water Treatment Division Manager with the City of Lawrence’s Municipal Services and Operations department, looking out over one of the basins at the Clinton Lake Water Treatment Plant.

When you turn on your tap for water in Lawrence, you expect water to come out.

That’s the biggest focus for Steven Craig, a water treatment division manager with the City of Lawrence’s Municipal Services and Operations department, and the others who work at the Clinton Lake Water Treatment Plant every day. The plant, at 2101 Wakarusa Drive, can process up to 25 million gallons of water each day, ensuring it is potable through a variety of treatment processes.

But as the water is filtered and treated, Craig said another focus has been to ensure that it is free of odor and weird taste. As recently as 2019 and 2021, the city has had to announce it would be treating water from the Clinton Lake plant multiple times to get rid of an “unpleasant taste and odor caused by algae.”

But this year? The water from the Clinton Lake Treatment Plant was recognized by the Kansas section of the American Water Works Association and the Kansas Water Environment Association for having the Best Tasting Tap Water in Kansas.

Through adjusting its treatment procedures and partnerships with the Kansas Biological Survey, the team at the treatment plant has worked to find ways to improve the water quality and be proactive for treating the algae-caused taste issues. After big investments from the city to improve the plant, the accolade highlights the progress the plant has made.

It’s a great honor and a point of pride for the staff,” Craig said. “Winning the best-tasting water award shows the progress we’ve achieved from addressing taste and odor issues.”

• • •

The main culprit for the earthy or musty taste and odor from some water coming out of the tap is a byproduct of blue-green algae called geosmin.

Geosmin is a naturally occurring compound that is created by blue-green algae. While it is not harmful to drink, even tiny amounts can cause a strong earthy or musty smell that people with sensitive palates can notice right away, Craig said.

The issue is often seasonal, since blue-green algae normally is at its highest in the warmer months of the year. Warm water and nutrients that come into the lake from runoff like fertilizer also help create conditions for the blue-green algae to grow, and make it more likely to cause issues with water odor and taste.

Trevor Flynn, an assistant director with MSO who oversees water treatment and environmental concerns, said blooms have to do with “water temperature and seasons.” The most common times for blooms are right when the lakes and air start to warm up and also toward fall when there can be fluctuations in temperature. Other factors like changing water levels or more runoff entering the lake can create different conditions at any time.

“Lakes are very dynamic,” Flynn said.

Craig said although the raw water gathered from Clinton Lake often looks clear — especially compared to water collected at the Kaw River Treatment Plant, Lawrence’s other source of water — it is often more difficult to filter than river water. While the water from the Kaw has a higher hardness and can become more “dirty” after large rainfalls, because the water in the lake isn’t flowing like a river, it doesn’t filter as naturally.

“It’s harder to get the particles out,” Craig said.

photo by: Bremen Keasey

Water flowing at the Clinton Lake Water Treatment Plant in Lawrence. Water from the plant recently won an award for best tap water in the state of Kansas.

• • •

Following a serious blue-green algae event in the summer of 2012 when geosmin levels were recorded four times higher than the previous record high and taste and odor were impacted for about 10 days, the city began to invest millions more in the plant to better treat the water, as the Journal-World reported.

Craig said the staff at the treatment plant implemented “both operational and treatment adjustments to improve water quality.”

One example of a change was finding ways to lower the turbidity of the water — a measure of water clarity. Water that has a higher turbidity level appears cloudy due to suspended particles like soil or algae.

As the plant treats the raw water, it adds carbon powder, which clings to the geosmin and other compounds and traps them. The cleaner water then enters a different basin that adds disinfectant chemicals like chlorine to kill harmful pathogens.

photo by: Bremen Keasey

A basin at the Clinton Lake Water Treatment Plant which has carbon powder. The powder is part of the standard water treatment, and it helps clear out compounds called geosmin, which comes from blue-green algae that cancreate taste and odor issues with the water.

One potential disadvantage with that process is that if those carbon compounds enter the second basin, it can react with the chlorine and cause “desorption,” which means the absorbed compounds like geosmin can be released from the carbon.

After the 2012 event, Craig said the staff took water samples from the first and second basins. Although the levels were low after it entered the first basin, once it reached the second basin, the levels of geosmin increased again, indicating there were high levels of desorption from the carbon compounds “carrying over” into there.

After that was discovered, the team began to find ways to improve the primary carbon treatment, Craig said, and added methods that were better at “pulling out” all of those particles before that second phase. That included adding more coagulants that can “grab onto” those compounds better to sink them to the bottom so they won’t filter on to the next basin.

Craig said that the EPA recommends that safe drinking water be below a turbidity level of 3 nephelometric turbidity units, or ntus. When the team at Clinton Lake measures the turbidity after treatment, Craig said it is at less than .1 ntus.

As well as creating a solution to that initial turbidity issue, Flynn said the team at the plant is testing the drinking water from 120 locations each week to ensure its quality. They also test different levels of chemicals to find the perfect levels for treatment.

“They are always trying to optimize the process here,” Flynn said.

• • •

Along with improvements at the plant, the water treatment team has partnered with another group to get a better view of conditions at the lake.

Flynn said the plant started a partnership with the Kansas Biological Survey at the University of Kansas to better track and predict algal blooms. Their team of researchers added a buoy in 2021 that helps track the climate of the lake.

Flynn said the buoy provides the plant more real-time data to see conditions at the lake and gives them “an idea of where taste and odor compounds would go.” That data can help the treatment plant team be more proactive to potential blooms than reactive, which means they can make a decision to add more carbon treatment to decrease geosmin levels.

Craig said data from that research also found there might be a “sweet spot” level of where the plant could draw the water that would have less chances of pulling lots of geosmin. Additionally, the data suggested at a certain lake level, it makes sense to take in a lower level of water to avoid the prolonged taste or odor event, Flynn said.

photo by: Bremen Keasey

One of the water basins at the Clinton Lake Water Treatment Plant. The plant can treat up to 25 million gallons a day.

Although it’s not a perfect science with the lake always fluctuating, Flynn said the partnership has given even more data to the plant, which gets about 100,000 different data points a day. Having the boots on the ground at Clinton Lake also means that researchers who might notice certain conditions can communicate faster with the plant and alert them to changing conditions.

The collaboration has meant that prolonged odor and taste events are able to be nipped in the bud much faster, Flynn said. Instead of reacting over an extended period of time — varying levels of carbon treatment if they get complaints about the odor in the water — the advanced tools from the buoy help taste and odor events become shorter.

That also helps the plant save money. Carbon powder is the most expensive chemical the plant uses, and during prolonged taste and odor events, Craig said they can spend up to an additional $3,000 to $4,000 per day on carbon. Being able to be proactive due to the increased data has helped the plant save considerable resources.

“It’s been a good investment that has pretty much paid for itself,” Flynn said.

• • •

Although Lawrence’s water previously earned a similar award for best-tasting water in the state in 2019, that water came from the Kaw River Treatment Plant.

It’s a point of pride for the Clinton Lake Treatment Plant team to have earned the honor this year, but especially so when compared to what other teams can offer.

Flynn said that other plants they competed with at the state competition had “superior technology” to what Lawrence had. That included things like reverse osmosis treatment technology and ozone treatment, which cost “millions and millions of dollars,” Flynn said.

Next year, the team will have a chance to compete in a national competition to see which communities in the country have the best tap water. It’s a far cry from when the city had frequent complaints about the taste and odor, and Craig said it is nice recognition for the progress the team has made.

“It highlights the hard work of our operators and the value of the partnerships we’ve built to ensure Lawrence residents have water that’s not only safe but also among the best in the state,” Craig said.

photo by: Bremen Keasey

The Clinton Lake Water Treatment Plant, at 2101 Wakarusa Dr. in Lawrence. After previous complaints from customers on taste and odor issues, upgrades and partnerships have help the city’s water treatment team earn an award for the best tap water in Kansas.