Leonard’s legacy: More than 60 years later, KU awards posthumous athletics letter to black runner once snubbed by coaches

The late Leonard Monroe, seen here in 2015, played basketball during the days of Jim Crow as a member of the Promoters, an all-black high school basketball team active from the 1920s until the 1950s.

Leonard Monroe knew he could run. After running the quarter mile in just 48.9 seconds — nabbing the second-fastest time in the state, he said — during his senior year at Liberty Memorial High School, now known as Lawrence High School, Monroe could be sure of that fact.

He thought his talent alone would be enough to impress the track and field coaching staff at the University of Kansas, the school Monroe chose to attend despite multiple scholarship offers elsewhere.

But this was 1951, and Monroe was black. When the young man showed up for the first day of practice that spring, head track coach Bill Easton told him there was no chance of him ever competing as a Jayhawk.

“He said, ‘You’ll never run for me,'” Monroe recalled to the Journal-World in 2015. “I was so heartbroken it was pitiful.”

Monroe’s oldest son, Michael, heard stories of Jim Crow-era Lawrence from his father growing up. Despite the injustice of his rejection from the KU track and field team he so admired, Leonard Monroe never let the incident “define him,” Michael said.

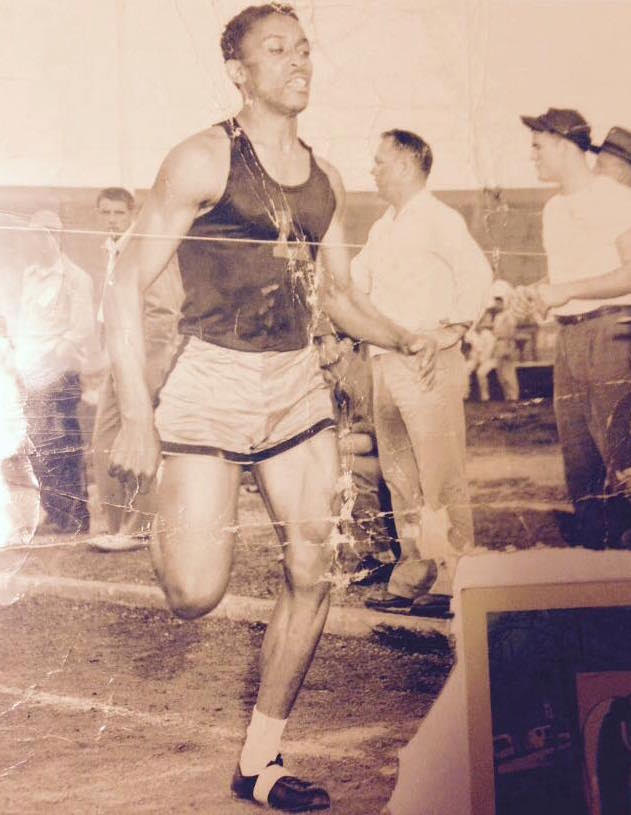

Leonard Monroe, pictured here as a young man, was the second-fastest quarter-mile runner in the state of Kansas while attending Lawrence High School. Monroe, who graduated in 1950, dreamed of running at the University of Kansas — until the team's head coach told him he'd never be allowed because of his skin color.

The late Monroe, who died last month of natural causes at age 86, remained a Jayhawk fan all his life. So, when the KU track and field department — along with the K Club, KU’s letter winners’ association — presented Leonard’s family with a chenille letter “K” at his December funeral, Michael knew just how proud his father would have been.

“I wish he would have known that that had happened,” Michael said. “But I think he does know, somewhere, that it happened.”

Despite the prejudice Leonard faced in his life, “I don’t think he was a prejudiced person himself,” Michael said of his father, who told Michael and his five siblings stories of segregated Lawrence restaurants and movie theaters. “He was able to overcome that, but we were cognizant in our lives of those kinds of issues.”

Leonard’s rejection from KU’s track and field team was hardly his first (nor his last) brush with racism in Lawrence. As a student at Liberty Memorial High School, he competed on a separate, all-black high school basketball team called the Lawrence Promoters. Jim Crow laws kept sports leagues segregated until 1950, Leonard’s senior year.

As a teen track star, he turned down several scholarships, all of them to black colleges, because he dreamed of running at KU. Schools with majority-white enrollments weren’t keen in those days to offer scholarships to black athletes — if they allowed them to play at all, said Jesse Newman, a childhood friend of Leonard’s and author of “Local Sports Hero: The Untold Story of the University of Kansas Sports and Wesley B. Walker.”

Leonard Monroe (no. 26) is pictured here with teammates from the 1950 Liberty Memorial High School (now known as Lawrence High School) basketball team.

“At this period of time in segregation, the school system didn’t look at us going into the universities and moving forward into the greater realm of society. That was reserved for the white population,” said Newman, 75.

Newman’s father, Jesse Newman Sr., played for the Promoters as a Liberty Memorial High School student in the 1930s. His cousin, Wesley B. Walker, was a skilled basketball player in Jim Crow-era Lawrence, even attracting recruiters from the Harlem Globetrotters’ farm team. Still, Newman argues, his cousin could have played with Wilt Chamberlain at KU if the school’s basketball recruiters had given him any attention.

So, he joined the army instead. “If we were going to do anything with our lives, we had to go into the service,” Newman said.

And that’s what Leonard Monroe did, too. Heartbroken after his encounter with Coach Easton, Leonard dropped out of KU and enlisted in the Air Force. He served during both the Korean and Vietnam wars, and found himself stationed in Japan, Europe, Vietnam and later New Mexico, where he met his future wife, Jackie.

After 23 years in the Air Force, Leonard retired and moved back to Lawrence, where he spent another 23 years working as the city’s supervisor of vehicle maintenance until retiring in 2000.

For Leonard, Lawrence would always be home.

“He was willing to give everybody the benefit of the doubt, and he could bond with just about anybody,” said Michael Monroe. “Whether it was the people he worked with at his garage, people in the community, people in the church, people at the ball field — he was very generous in his friendships.”

Leonard had friends in high places, too, including KU Athletics. He even forged a friendship with former KU basketball coach Roy Williams during Williams’ tenure with the Jayhawks, Michael said, but never once mentioned his painful experience as a KU student to the legendary coach.

“It took somebody outside the family” to finally make good on Leonard’s connections, Michael said, and award him the athletics letter he so rightly deserved. Enter family friend Natasha Riggins, who contacted KU Athletics in December after hearing from Maria Monroe about her father’s passing.

Riggins, who said she and her parents had been “kicking around” the idea for months, knew she would have to work quickly to have the chenille letter “K” ready in time for Leonard’s funeral. Fortunately, the response from current track and field coach Stanley Redwine was almost immediate, said Riggins, who also found an ally in K Club senior director Candace Dunback.

After receiving “dozens” of emails from former KU athletes writing in support of Leonard, Riggins said, Dunback called Riggins on Dec. 14, three days after Leonard’s death. The letter “K,” along with a letter written by Dunback addressed to Leonard’s family, was presented to Maria Monroe the morning of her father’s funeral, Riggins said.

Leonard loved people, and his funeral was evidence of that. Riggins said services were standing room only at St. Luke AME Church that day, as community members paid tribute to the man who had become a beloved fixture in his hometown over the years. The sanctuary was filled with emotion as Maria Monroe read the K Club’s letter aloud, Riggins said, remembering the clapping and cheering that followed.

“I think he would have been proud that justice was served,” Riggins said of the moment. “And proud to be a member — an official member — of the KU athletics community that he so adored.”

Michael Monroe agrees. His father supported KU sports throughout his life, notably cheering from the sidelines as his son, Darryl, played as a center fielder for the 1993 KU baseball team that reached the College World Series.

Leonard’s family — including three children who went on to earn degrees from KU — remains his greatest legacy, Michael said of the eternally “proud” father and grandfather.

“He’s just an example of somebody that overcame adversity,” Michael said.

“Sometimes it takes a long time, but a lot of times, people will end up doing the right thing if you give them the opportunity to do so,” he added, referring to his father’s posthumous honor. “And I think the right thing happened here.”

- The late Leonard Monroe, seen here in 2015, played basketball during the days of Jim Crow as a member of the Promoters, an all-black high school basketball team active from the 1920s until the 1950s.

- Leonard Monroe, pictured here as a young man, was the second-fastest quarter-mile runner in the state of Kansas while attending Lawrence High School. Monroe, who graduated in 1950, dreamed of running at the University of Kansas — until the team’s head coach told him he’d never be allowed because of his skin color.

- Leonard Monroe (no. 26) is pictured here with teammates from the 1950 Liberty Memorial High School (now known as Lawrence High School) basketball team.