Proposed expansion could allow Douglas County Jail’s environment to catch up with mental health programming

Douglas County Jail

Douglas County Jail expansion

This is the fourth story in a series exploring the needs Douglas County Sheriff’s Office officials say are driving the proposed $30-million expansion of the Douglas County Jail. Past stories is the series were:

? 2017 to be year of decision on Douglas County Jail expansion; a look at current plans

• Spike in Douglas County Jail female population hinders operations, programming

• Douglas County Jail re-entry program suffers from ‘farming out’ of low-risk inmates

The series will look next at the plan to add male and female pods observe and classify the risk level of new inmates entering the Douglas County Jail.

The cell blocks at the Douglas County Jail are not inviting places, but those who know the jail say the third-floor special-management unit is the most depressing.

“We call it the special management unit, but I maintain it is really a segregation unit,” said Mike Brouwer, director of the jail’s re-entry program. “It’s the unit with the least amount of sunlight in the building. It’s the only unit that has metal toilets and metal sliding doors. It has smaller day rooms; a smaller recreation area. It was never designed for special-needs populations.”

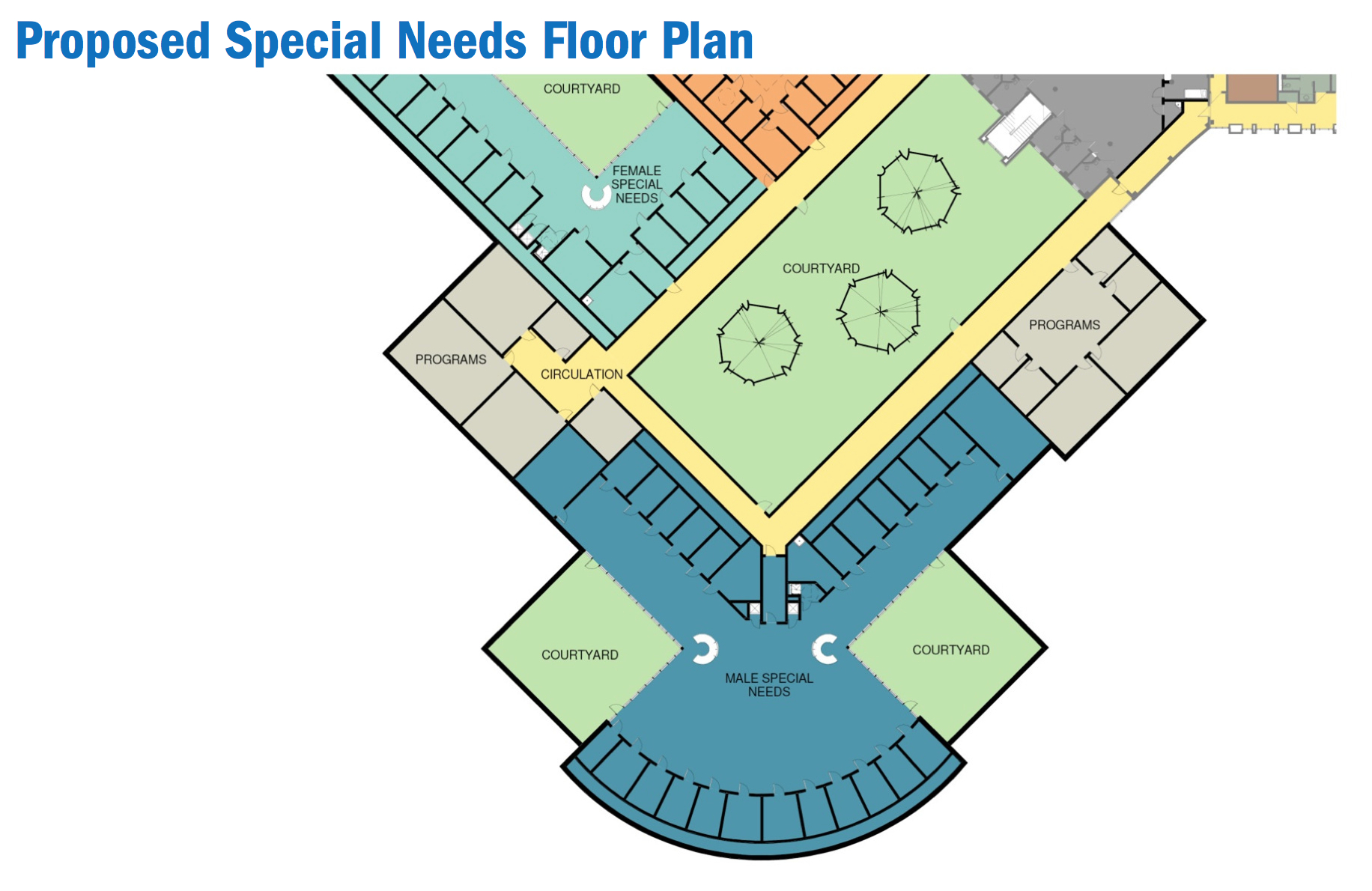

The plans Treanor Architects developed for the Douglas County Jail would build male and female mental health pods on the facility's ground floor. The design incorporates the calming features of natural light and an open-air courtyard.

To an outsider, it might seem as if special-population inmates would be assigned to a special-management area, but they are two distinct classifications at the Douglas County Jail. The special-management cells are meant to house inmates whose crimes or disciplinary problems require that they be segregated from other inmates in the single-bed units. Special-needs populations are those with mental illness or other medical or physical conditions.

Because there is no pod for inmates with mental illness at the county jail, male inmates in crisis situations are placed in the special-management area where they remain in their cells at least 22 hours a day with little interaction with correctional staff until they stabilize. That forces inmates in mental health crisis to spend a lot of idle hours dealing with their demons.

“In reality, someone who is in crisis and actively symptomatic is not going to do a lot of sleeping or any reading,” Brouwer said. “It’s tough. In the other jail I worked at, the inmates were unlocked for as many hours a day as possible. We kept them out in the day room as much as we possibly could.”

At the Douglas County Jail, the inmates in crisis tend to stand by the doors of their special-management cells, hoping to engage in conversation with any inmates or correctional officers who may be near, said Cindy Naff, a Bert Nash mental health clinician at the jail.

Women undergoing a mental health crisis aren’t placed in a special-management unit because there is no such thing at the jail, but only a single female pod that houses all women from special management, special needs and minimum, medium and maximum security. That forced mixture of populations can create more problems.

“We have issues with triggering,” said Kelli Ziegler, Bert Nash jail re-entry specialist. “An inmate may be OK on the women’s side, and we bring in another inmate in crisis who is screaming. That can put a lot of trauma on someone who may have been handling it well and trigger a response.”

The jail currently has no mental health areas, or pods, for the 30 percent of the jail’s population with mental illness and 18 percent with severe and persistent mental illness. Once male inmates are stabilized in the special-management unit, they are placed in the appropriate pod for their security-risk level where they get increased out-of-cell time and access to more programming. Women stay in the jail’s single female pod.

“We have folks with serious mental illness all over the facility,” Brouwer said.

Improving mental health care and access for inmates is one of the motives behind the estimated $30 million, 120-bed expansion of the Douglas County Jail once it is formally proposed, most likely in 2017. The project, though, will require public financing, and likely will require some public convincing. Already some groups have expressed opposition to the idea, instead urging the county to focus more on reducing inmate totals and build a crisis intervention center, which the county also has proposed.

The expansion would build what Brouwer and Bert Nash jail team leader Sharon Zehr say would be a therapeutic environment where inmates could receive treatment and prepare for success outside the jail’s walls. Among the building program’s features would be a 28-bed male mental-health pod and an adjoining female pod with 14 beds. The pods’ designs include such calming features as an abundance of natural light, a large day room area and open-air courtyards. The pods will also have offices for staff and space for existing and expanded programming.

Although the jail currently lacks appropriate space for inmates with mental illness, Douglas County Sheriff Ken McGovern has made a commitment to their needs through staffing and programming, Brouwer said.

“The amount of staff we have per inmate I am confident is the best in Kansas,” he said. “The number of programs we have I know is the most.”

Through its partnership with Bert Nash, the jail has a continuum of mental-health programming from booking to post-release.

The effort starts at booking when inmates are asked a long list of questions to help determine their mental states and level of chemical dependency, Brouwer said. Inmates who are Douglas County residents and arrested for nonviolent crimes are eligible for the Access, Identify and Divert program that is offered through two Bert Nash Community Mental Health employees hired in January with a two-year federal grant, which continues through 2017. The two AID evaluators determine which inmates should be placed in appropriate alternative settings.

Bert Nash’s involvement continues through Zehr’s and Naff’s work with inmates with mental illness to stabilize and improve. In addition to individual and group therapies on a number of topics, they work with the inmates on changing criminal thinking and addressing chemical or alcohol dependency. That’s a big task because 70 to 80 percent of inmates with mental illness are substance abusers, Zehr said.

Ziegler helps inmates prepare for release and aids them once they are back in the community. That latter effort involves connecting them with community resources, reminding released inmates of appointments or even giving them a ride to appointments, she said.

Brouwer and the jail’s Bert Nash staff expect the proposed mental health pods’ therapeutic environments would be an asset in helping inmates recover, but they also see the value of having the mental health target population and resources serving them in one place. The addition would free clinicians from working around the daily schedules of the jail’s pods, especially the complex daily timetable in the catch-all female pod, Zehr said.

The jail would increase its Bert Nash presence should the mental health addition be built.

“Right now with the two grant positions, we have one clinician for every 60 inmates, which is a pretty good ratio,” Brouwer said. “We look to continue those positions and add one more clinician with the expansion with the option of adding another should the jail population increase. We would also increase the number of hours we provide psychiatry. We now provide five hours of psychiatry a week. We’re thinking about increasing that to eight to 10 hours.”

Continued and better mental health programs will be needed at the jail even should a mental health crisis intervention center be built, the behavioral health court completely developed and other diversionary programs being explored fully implemented, Brouwer and the Bert Nash team insist.

“I’ve heard people say the crisis center would divert 30 people from the jail a day,” he said. “I’m not sure where that’s coming from because we’re not seeing those kinds of numbers anywhere in the state with the other three crisis centers. Johnson County with a population of 500,000 is diverting an average of two people a day from the county jail to their crisis center. With 17,000 bookings a year, that’s not a significant portion.”

As for the behavior health court, it would be important to get the right people into the program, and those are high-needs inmates, requiring intensive supervision, Brouwer said. They would be few in number, but would make a noticeable difference at the jail because those inmates place a great demand on the facility’s resources, he said.

“We visited the mental health court in Topeka, and at that time they were serving 12 people,” he said. “This last month, they were serving five people. So it’s not having a huge impact on the jail population. Those programs are not about reducing the jail population but about doing the right thing for those people.”