The making of ‘K2’: Court records detail origin and boom of synthetic marijuana

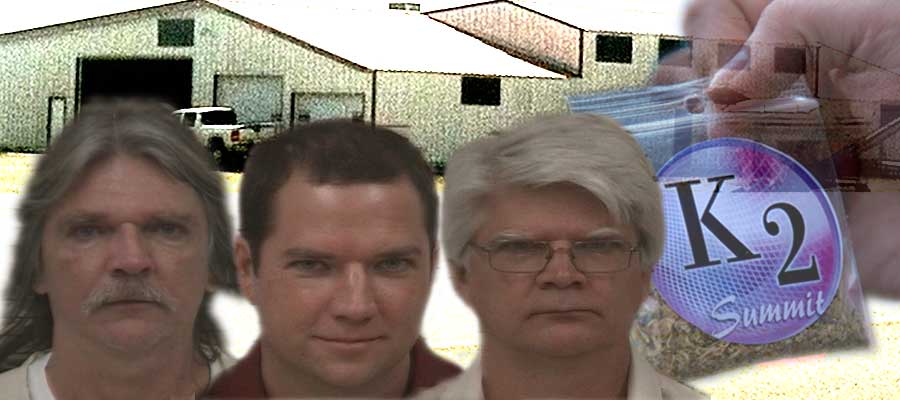

Journal-World graphic

A packet of K2, a synthetic marijuana-like product that was sold in Lawrence in 2009.

Jonathan Sloan.

Bradley Miller

Clark Sloan.

In 2009, a mysterious product called “K2” hit the shelves of the Lawrence herbal store Persephone’s Journey.

It was labeled as an incense, but no one was fooled; smoking the substance produced a marijuana-like high. The best part? At the time, the compounds were legal in Kansas.

Little was known about where the mixture was coming from, what was in it or how it was made, but one thing was crystal-clear: Customers loved it. On any given day in fall 2009, a line could be seen snaking out of the store along Massachusetts Street.

A trio of men, indicted last week for their role in selling and manufacturing the synthetic marijuana product, were warned about the murky legal territory of their multimillion-dollar K2 operation, as well as the potential health dangers of the substance.

But the millions of dollars the sale of K2 raked in were too just too much to resist, according to federal court documents released last week.

Jonathan Sloan, 32, of Lawrence; his father, Clark Sloan, 54, of Olathe; and Clark’s brother Bradley Miller, 55, of Wichita, all face charges in the case, in which prosecutors allege the men made more than $3 million selling K2 and other synthetic compounds. If convicted, the men could land behind bars for the rest of their lives.

$10K per day

According to court records, K2, which came in a variety of strengths and strains, was conceived in early 2009 by Miller following a trip to China. At the time, Miller and Jonathan Sloan co-owned the Lawrence herbal store Persephone’s Journey, which would later become Sacred Journey, at 1103 Massachusetts St.

The two purchased JWH compounds — synthetic versions of the active ingredients in marijuana — added in a solvent such as alcohol or acetone, and sprayed the chemicals on herbs. The duo began selling K2 at Persephone’s Journey and online through Jonathan Sloan’s herbal distribution business, Bouncing Bear Botanicals, based in Oskaloosa.

Sold for about half the price of marijuana, K2 also had an added benefit: users on parole or probation wouldn’t test positive for drug use.

The money poured in. In October 2009, Clark Sloan emailed his son to discuss just how much money K2 sales were pulling in both in retail and website sales: more than $100,000 in one nine-day span.

Not under the radar

The rise of K2 in the Lawrence and the Kansas City metro area caught the eyes of law enforcement officials. After seizing K2 packets during arrests in 2009, scientists at the Johnson County Sheriff’s Office tested the substances and identified the parallels to marijuana.

At around the same time, poison control centers across the country began warning about K2 and other synthetic drugs, after users showed up at hospitals with a variety of symptoms not associated with marijuana, such as racing heartbeats and panic attacks.

While the compounds in K2 were similar to the active substances in marijuana, the specific chemicals had not yet been banned in Kansas or any other state.

Bouncing Bear Botanicals was housed at this warehouse in Oskaloosa on U.S. Highway 59. The business, owned by Jonathan Sloan, manufactured 'K2', a form of synthetic marijuana. In 2010, federal and local law enforcement raided the business.

K2 timeline

• Nov. 4, 2009: New, legal, drug has law enforcement concerned — and it’s already on a Lawrence store’s shelves

• Jan. 11, 2010: Legislator, law enforcement officials call for end to K2

• Jan. 21, 2010: Senate approves bill to ban sale of K2

• Jan. 25, 2010: Woman says K2 eases pain from chronic illness

• Feb. 4, 2010: Lawrence’s Sacred Journey closed, under investigation by federal officials

• Feb. 5, 2010: Lawrence man charged after Sacred Journey investigation

• Jan. 6, 2011: Criminal charges re-filed against Lawrence man at center of K2 case

• April 7, 2011: Synthetic drugs such as K2 send thousands to ER

• Sept. 2, 2012: Kansas, nation can’t always keep up with constantly changing synthetic drugs

• April 3, 2013: Local men at center of local K2 synthetic marijuana controversy brought up on federal drug charges

For more articles on K2, click here

That didn’t necessarily mean the Sloans and Miller were in the clear. Federal laws allowed for prosecution of selling and manufacturing substances that have a similar effect as an illegal substance. Concerned about the potential unknown dangers of the K2, police contacted Kansas lawmakers in late 2009 about a bill to outlaw the chemicals.

In December 2009, Clark Sloan sent Jonathan Sloan an email referencing the potential legal implications of their booming business.

“I’d say milk K2 for a few more months. $150,000 a week isn’t too bad… So, get a couple million over the next few months. Then sell it – at an even higher price,” Clark Sloan wrote. “But… Too scary. Not worth 20 years in San Quentin.”

As lawmakers debated a potential ban on K2 in 2010, the Sloans and Miller explored overseas options for their booming business, according to the court documents.

A slew of wire transfers to offshore bank accounts, along with an email trail, detailed plans to ship the product to South America and Russia. A potential customer in Russia, identified only by the name “Vladimir” in court records, wanted to buy K2, but told Miller the compounds were illegal in Russia.

“So we need to find a non-typical method of import,” Vladimir emailed Miller in 2009.

Miller responded, writing that they could send K2 and label it as tea to skirt any problems exporting the product to Russia. Whatever it took, Miller said he’d make sure Vladimir got his hands on a “million-dollar cash cow.”

“This is a good one and a gold mine. Our problems will only be able to keep supplies up with demand,” Miller wrote. “And those are the kinds of problems that we enjoy, right?”

Trouble

In early 2010, Kansas lawmakers passed a bill banning the JWH compounds in K2, effective July 1, 2010. Jonathan Sloan, seeking to prevent such a ban, spoke to legislators at a hearing on the bill, to no avail.

On Feb. 4, shortly after the ban passed, and as K2 kept flying off the shelves at Sacred Journey, federal and local law enforcement raided the Bouncing Bear Botanicals warehouse in Oskaloosa, as well as Sacred Journey.

That day, Clark Sloan, Jonathan Sloan and Miller were arrested and later charged with more than a dozen offenses in Jefferson County, including possessing illegal drugs such as mescaline and LSD. But none of the charges related to the then-still-legal production of K2.

A Colorado River Toad, similar to ones seized during a raid of Bouncing Bear Botanicals. Bufotenine, an illegal hallucinogen, can be extracted from the toads' glands.

Among the items seized by law enforcement as part of the investigation: thousands of cactus plants, 20 toads — whose glands could potentially be milked to produce banned hallucinogens — and $700,000 in cash.

Officials from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Johnson County Sheriff's Office and Lawrence Police Department, conducted a search and seizure in February 2010 inside Lawrence's Sacred Journey — a store at the center of the K2 controversy in Kansas.

State Rep. Rob Olson (left) and Johnson County forensic scientist Jeremy Morris in January 2010 display the K2 product that they want banned because it contains synthetic substances that mimic the effects of marijuana. Olson, R-Olathe, and Johnson County law officers held a news conference at the Statehouse on the first day of the 2010 legislative session.

But the charges were dropped. The Sloans and Miller were charged again in 2011 in Jefferson County, but those charges also were dropped.

The Kansas Attorney General’s Office, which spearheaded the local drug case, worked with the U.S. Attorney’s Office on the current charges, said agency spokesman Don Brown.

Brown did not provide specifics about why the Jefferson County charges were dropped, but said his office supports “the filing of federal charges as the best course of action.”

More trouble

In the end, it wouldn’t be the legality of the substances in K2 that would get the Sloans and Miller in legal hot water. Following the 2010 raid, store representatives said they would no longer carry K2, and the court records do not indicate that the Sloans and Miller sold or manufactured the product after the ban.

It was how the trio labeled and marketed K2, as well as several other products, that led to a grand jury indictment alleging Food and Drug Administration violations.

They marketed K2 as “all-natural,” though it contained synthetic compounds. Marketing of K2 also included claims that the product was safe and posed no risks, and could help cure a variety of ailments.

A brochure at Sacred Journey included the following statement:

“Evidence suggests that compounds such as JWH-018 and JWH-073 could help reduce the chance of developing prostate cancer and possible other cancers, and are currently being researched as a treatment for depression and anxiety.”

That was before news stories began cropping up detailing potential health risks associated with K2, followed by the production of spin-off synthetic substances sprayed on bath salts.

In 2010, for instance, a Kansas University student who had smoked a newer version of synthetic marijuana was killed after hallucinating and running into traffic on Interstate 135 near Salina.

As news trickled in that K2 could be dangerous, the Sloans and Miller took note, according to court records, emailing each other news articles and other anecdotal stories about adverse effects of K2.

Clark Sloan, in an email to his son in early January 2010, wrote:

“Don’t know what it really does, or what it might do. And I don’t have any confidence that Brad (Miller) mixes it up 100% the same everytime. What happens when he forgets he already added the JW and adds some more? What might happen if some kid is taking some xanax or something and combines K2. All kinds of unknowns. Just a spooky product to me.”

But again, the lure of the cash kept the business going. Days later, Clark Sloan emailed the following to his son:

“Your deposit was 272,000. . . K2 is kinda fun with the $ isn’t it? Be cool if we could stall all legislation for say, a year or more, and just rake in the doe for a while. You could easily be pulling in $300,000 a week on it.”

All K2 banned

In 2011, Kansas lawmakers banned more chemicals similar to those found in K2. Numerous other states, and the federal government, have followed suit, banning K2 and similar products that cropped up across the country.

Sacred Journey remains open in Lawrence, but stopped selling K2 following the 2010 raid. Jonathan Sloan’s Bouncing Bear Botanicals business continues to operate and sell herbal products online.

Tom Bath, an attorney for the Overland Park law firm Bath & Edmonds, which is representing Miller and the Sloans, said their office is reviewing thousands of pages of documents in the case.

Bath said the case is “complex,” and that it would be premature to say anything other than they’re going through the indictment.

Several of the charges carry penalties of up to 20 years in prison each, if convicted.