Cicadas’ summer song hits high-volume pitch

Ah, the racket of unbridled courtship.

No, it’s not the clamor of recently arrived Kansas University students. Rather, it is other loud, late-summer lovers: cicadas.

“It’s an indication of the season,” said Michael Greenfield, a KU biologist who has studied the high-pitched din of cicadas for years.

But for whatever reason, this year’s din seems a bit louder, transforming typically quiet neighborhood and tree-lined streets into a tiny buzz, like some odd siren sounding for hours every night.

So what’s the deal? Is this some kind of cicada bumper crop? A so-called “brood year”?

Robert Bauernfeind, an entomologist at Kansas State University, may have an explanation.

Bauernfeind said this isn’t a periodic brood year, when cicadas that follow a 17-year breeding cycle emerge. That last happened here in 1998, bringing their mating call to a true scream.

“Especially in those years, they can make a tremendous din,” he said.

But there may be a population spike this year, Bauernfeind said.

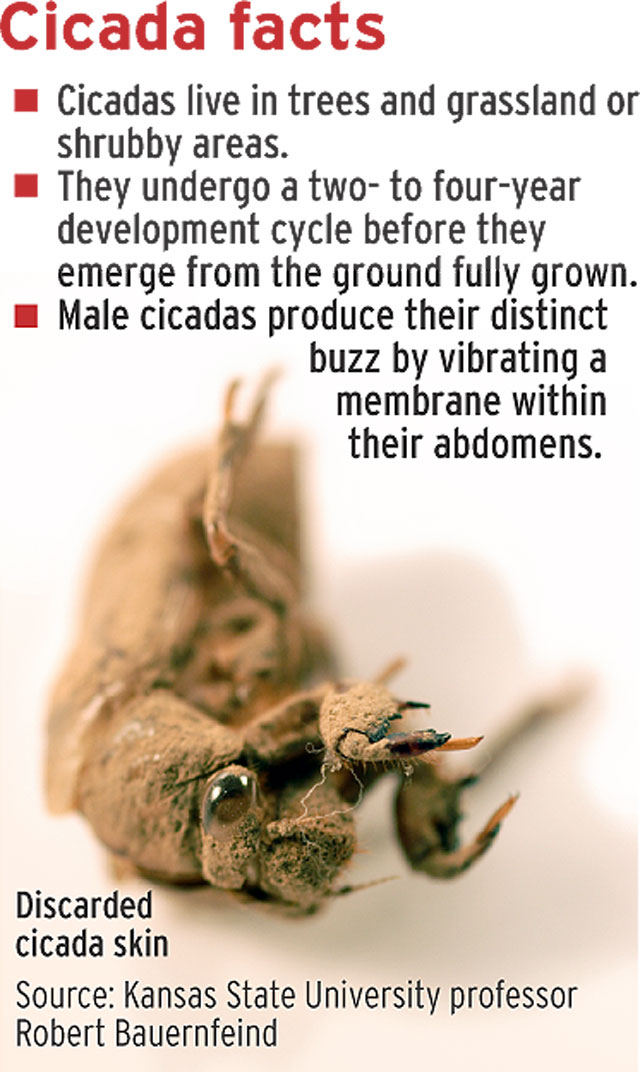

Though the biology of cicadas is still fairly mysterious, Bauernfeind said they are not annual insects. Likely, they have two-, three- or four-year life cycles and only emerge from their underground habitat when the time is right, he said.

Greenfield said cicada life cycles run between six and eight years.

“These things aren’t going to emerge until it’s their time,” he said.

And though there are at least two species of cicadas hovering in the trees and shrubs this time of year, Bauernfeind said it’s possible one of the annual broods was quite a bit bigger than normal this year. The logic goes: If a brood five or six years ago was larger, it would follow that they would have more offspring and that brood – possibly this year’s – would be larger, too.

The phenomenon, which occurs in June beetles and other similar bugs, is called “Brood A,” he said.

“This may be one of these years where the numbers are higher,” he said. “It may be the way for cicadas.”

But studies don’t give a clear indication of the insect’s numbers. Cicadas aren’t particularly important economically, Bauernfeind said, giving researchers little incentive to study the creatures that live the majority of their lives underground anyway.

Neither people at the K-State Extension Office nor the state Department of Agriculture knew much to say about cicadas.

KU biologist Greenfield said he wasn’t surprised.

“No one has bothered to figure out how to rear them,” he said. With multiyear life spans, “not many people are going to embark on a study that takes that long.”

But for all of the lack of research on the critters, Greenfield said there are other factors besides brood size that can affect cicadas.

More about cicadas

For one, he said, bacteria or other underground pests can take their toll on cicadas during their below-ground life cycle. Hungry birds can feast on the bugs once they emerge.

But Greenfield has been keeping his ear to the trees and said it doesn’t seem like the annual high-pitched screech is any different from previous dog days.

“I really wouldn’t put any money at all in the likelihood that there are more of them,” he said.