State’s rural population continues to shrink

Say good-bye to small-town Kansas. It’s fading.

Three-fourths of the state’s 105 counties – all of them rural – lost population between 2000 and 2004.

And for the eighth consecutive year, 60 percent of the state’s school districts lost enrollment in 2005.

“Many districts are talking about consolidation,” said Jim Hays, a demographer with the Kansas Association of School Boards.

But that’s not to say it’s a popular topic.

“Many small, rural communities believe that without a local attendance center – at least an elementary school – they have no hope of attracting young families to live there,” Hays said. “And then you have the sentimental aspects that come with closing a high school and the more tangible concerns over what happens to real estate values.”

Earlier this year, the Nes Tre La Go school district in Utica dissolved after its enrollment fell below 40 students. Ness County’s Ransom and Bazine school districts consolidated in 2004.

Today, at least six districts – all in counties bordering Nebraska – are publicly discussing consolidation:

¢ Jewell County – White Rock and Mankato.

¢ Washington County – Haddam and Washington.

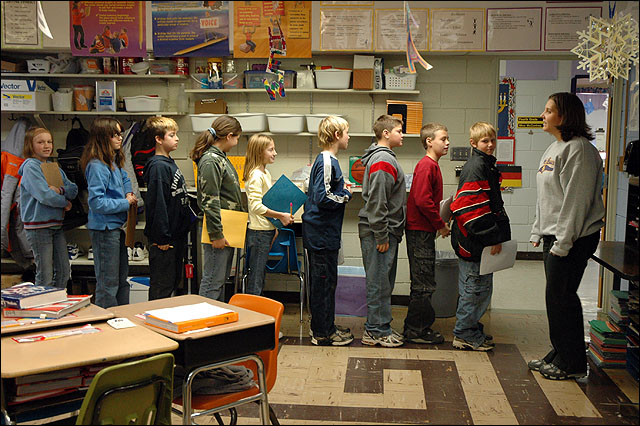

Most of the fifth-grade students in Gina Holwick's class at McLouth Elementary School line up to go to computer lab Friday. For the eighth consecutive year, 60 percent of the state's school districts lost enrollment in 2005. McLouth has lost enrollment six out of the last seven years.

¢ Republic County – Cuba and Belleville.

“This is my ninth year here,” said Belleville school Supt. Larry Lysell. “My first year, we had 640 students. Today, we have 455.”

The Cuba school district, he said, has fewer than 100 students.

“The goal is to keep something in Cuba for as long as we possibly can,” Lysell said. “We’re trying to take a negative and turn it into a positive for our students. That’s the main thing.”

Dying towns

The future is hardly bright. According to Kansas Department of Health and Environment, Republic County’s 83 deaths last year were offset by only 46 births.

“We’ve got to find things people can do to stay in Republic County,” said Lysell, who’s also active in the county’s economic development efforts. “What we have now is a sort of cycle – we give our kids a really good education, they go off to college and then they don’t come back because they can’t make the kind of money here that they can make in the larger cities.

“And then with fewer people here, we start to lose businesses,” he said.

Lysell said he’s also noticed young families are having fewer children than previous generations.

That’s true throughout the United States, Hays said. “The baby boomers had fewer children than their parents did and they spread their child-bearing over a longer period of time, in some cases waiting until they were in their 30s.”

Kansas public school enrollment peaked in 1973-74 at 479,344 students and in 1998-99 at 469,758 students. It’s at about 466,000 now.

“Those are the baby boomers and what’s called the ‘baby boomer echo’ or the baby boomers having kids,” Hays said, referring to the early 1970s and the late 1990s.

“Barring something really dramatic happening, one can speculate that in the foreseeable future, at least, we’ll never approach those numbers again,” he said.

That’s because the state’s farm economy requires ever-fewer workers, said Joshua Rosenbloom, director of the Center for Economic & Business Analysis at Kansas University.

“Rural communities are dealing with some really difficult economies,” Rosenbloom said. “At some point it becomes a little like trying to fight gravity.”

Fewer farms

- School enrollment estimates will sway planning for future (12-11-05)

- Photo gallery: Rural way of life at stake

- Rural population in decline (04-15-05)

- State stands to lose seat in Congress (04-14-05)

- Sebelius tells Legislature to get to work (01-02-05)

- Kansas population growth among nation’s slowest (12-22-04)

According to U.S. Census figures, Kansas had 110,000 farms in 1960. Today it has fewer than 64,000.

“You simply don’t need as many people to farm the same amount of land today that you did 10 or 20 years ago,” said Janet Harrah, director at the Center for Economic Development and Business Research at Wichita State University.

That’s not true just in western Kansas, said Jean Rush, school superintendent in McLouth in Jefferson County.

“Our counselor did an informal survey a couple years ago and found that we had only one family that made its sole living off of farming,” Rush said. “We had a lot that farmed on the side, but only one that farmed full-time. That’s a huge shift for this community.”

McLouth has lost enrollment six of the last seven years. It now has 553 students.

But McLouth, Rush said, is close enough to Lawrence and Kansas City that, eventually, housing developments will reach eastern Jefferson County, bringing children with them.

“I really believe it’s coming,” she said. “But right now housing availability in McLouth is really limited.”

Most small towns aren’t as fortunate.

A lone driver makes his way over a rural Jefferson County road south of McLouth. According to the U.S. Census, three-fourths of the state's 105 counties - all of them rural - lost population between 2000 and 2004.

“If you look across the country, the rural areas with the least growth are those that are not adjacent to a metropolitan area,” said KU’s Rosenbloom.

Those that have bucked the trend, he said, tend to be near recreational opportunities “like lakes or casinos” or have niche economies such as the meatpacking industry in Dodge City and Liberal.

But “these are exceptions rather than the rule,” said WSU’s Harrah, adding, “I don’t expect to see a turnaround.”

Getting older

Coupled with young families and high school graduates leaving, small-town populations are aging.

“We have many counties in Kansas where the median age is 50 – that means half the people are over 50,” Harrah said.

Jim Beckwith is executive director at the Northeast Kansas Area Agency on Aging based in Brown County, where the median age in 2000 was 40 and where one out every five people is 65 or older.

For comparison, Douglas County’s 2000 median age was 27; 8 percent of the population is 65 or older.

“The 80-acre farm is no more, and the kids are leaving for the high-tech jobs in the big cities,” Beckwith said.

“You may not see it there in Lawrence,” he told the Journal-World, “but out here this shrinking-population stuff is for real. Half the people I’ve got taking care of seniors are seniors themselves because the pool of caregivers just keeps getting smaller and smaller. You can’t get a young person to care for a senior when they can make the same money standing outside a casino (in neighboring Jackson County) saying, ‘Hi, welcome to Harrah’s.'”

The declines have the attention of Sen. Janis Lee, D-Kensington.

Kensington, population 500, is in Smith County, where almost one-third of the population is 65 or older and where school-district enrollment is below 200.

Last year, 65 Smith County residents died; 32 were born.

“It’s been devastating,” Lee said. “I don’t know the answer, but I think it’s pretty clear that economic efforts that have been undertaken in this state haven’t worked. I don’t think they have a clue what we’re dealing with out here.”