From a cap on music concerts to a new transit service to downtown, a look at what’s in proposed KU Gateway agreement

Agreement also raises possibility that end project could be smaller than envisioned

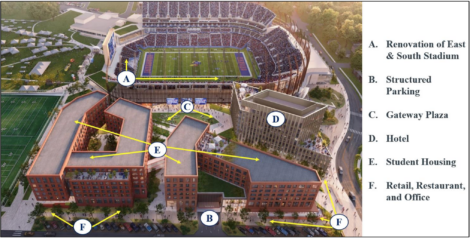

photo by: University of Kansas

A concept of KU's Gateway District, as provided to the Lawrence City Commission for review.

UPDATED 9:25 P.M. AUG. 11

They say football is a game of inches. So too, is an approximately $750 million redevelopment of KU’s football stadium, as evidenced by the thickness of the legal documents governing the project.

There’s a big — 262 pages — and important document up for approval Tuesday night. It is the development agreement between the University of Kansas and the City of Lawrence. As we reported Friday, approval of the document opens the door to about $95 million worth of state and local financial incentives that KU leaders say are critical to the completion of the KU Gateway District.

I strapped on my helmet and perhaps another piece or two of protective equipment to read through that stack of legalese to get a better idea of what the city and university would be agreeing to as part of this massive public-private partnership. Here’s a look at some key details.

— A missing number. The first thing to report is what is not there. A key portion of the agreement spells how many private dollars versus public dollars would be going into the remainder of this development.

As a reminder, about $450 million worth of the Gateway District is nearly complete as the west side and north end of the stadium have been renovated, complete with a new conference center. KU is seeking financial incentives potentially worth $94.6 million to help build the infrastructure for the second phase. That phase is estimated to cost about $300 million and would include a hotel to connect to the conference center, 1,000 parking spaces, restaurant and retail space and new student housing.

One portion of the development agreement — section 4.6(b), if for some reason you are following along — has a simple statement that the developer, KU, shall contribute (or cause to be contributed) a certain dollar amount in exchange for the maximum disbursement of the $96.4 million in public incentives. It is a key sentence that says if the project gets the full amount of incentives, then the developers must contribute a certain amount of money to the project.

However, upon reading the agreement included in the packet of Lawrence city commissioners, the required amount of contribution from the developers isn’t listed. There’s a blank for the number to be filled in, but as of this writing, the number hasn’t been included in the document.

Early Monday evening a spokeswoman with the city, in response to a Journal-World question, said via email that the private developers are anticipated to provide 83.33% of the the project’s funding, well in excess of the 50% minimum required by the state STAR bond law. The city, however, did not provide what that amount calculates to in terms of dollars, nor provide an explanation about why that portion of the agreement has been left blank.

— Wiggle room. If phase II of the Gateway District is expected to cost about $350 million in total, and the maximum amount of public financial incentives is $94.6 million, you might guess that the developer would have to contribute the difference between those two, approximately $255 million.

That may end up being the case, but not necessarily. The development agreement does acknowledge there is a possibility the project could be smaller than what is envisioned, if hurdles arise.

The agreement, section 2.3, states that KU would not be in default if KU fails to complete the hotel, the student housing, and the retail/restaurant portions of the proposed Gateway District. Rather, to be in compliance with the development agreement, KU must complete only the east side renovations to David Booth Kansas Memorial Stadium, 640 spaces of parking on the east side of the stadium, and an approximately 20,000-square-foot outdoor plaza area that would be designed to host community functions and entertainment.

How likely it is that KU would move the project ahead if it couldn’t do the other components is an open question. All discussion has highlighted that the hotel component of this project is critical. KU is concerned that the conference center and its 1,000-seat banquet room will struggle if it doesn’t have a hotel connected to the event space.

Whatever the likelihood of a smaller project, it is worth noting that the development agreement has some wiggle room on what constitutes a completed project.

— Completion date: That list of what elements must be completed is called the “minimum improvements” in the agreement. The agreements states those improvements must be completed by Dec. 31, 2028.

— Concert cap. Multiple KU officials, including the chancellor, have said they envision the renovated stadium becoming a site for major music concerts. Of course, the stadium is right next door to a residential area, so it is not surprising that the development agreement puts some caps on that type of use.

The agreement, section 7.2(i) says the stadium can’t host more than eight major concerts per year at the stadium. Any such concert also would have to end by 11 p.m.. The agreement defines a “major concert” as a concert that is projected to have an attendance of 30,000 people or more.

— Housing deal. As we reported on Friday, the development agreement requires KU to create a new off-student KU housing office, which appears to be an effort to provide an official place where KU and the city can work together on problems that occur with students living off campus. KU has two years to create that office.

That’s interesting, but the bigger housing component might be a separate clause in the agreement. Section 8.5 of the agreement states: that KU “will make a good faith effort to provide and maintain housing to support no less than 25% of full-time undergraduate enrolled students living in the city.” In other words, Lawrence would like at least 25 percent of all the students at the Lawrence campus to live on campus or in Greek housing. Presumably that provision is designed to reduce the pressure that students put on the overall housing market in Lawrence.

KU is probably close to that today. Statistics from KU stated just more than 6,000 students lived in campus housing in the Fall 2024 semester. That number doesn’t include Greek housing, which the development agreement counts as campus housing. KU had about 24,000 full-time equivalent students on its Lawrence campus in Fall 2024. Using that number, meeting the 25% on-campus-goal would mean about 6,000 on-campus living units. That’s about what KU has today.

The significance seems to be that KU is saying that if KU grows its enrollment in the future, it expects KU to also grow its on-campus housing offerings. KU seems to be on that page as well. After all, the Gateway project is envisioned to have more than 400 new beds of student housing. Plus, as we’ve reported, KU has received approval from the Kansas Board of Regents to issue up to $100 million in new debt for additional student housing in the coming years, if needed.

— Transportation service. Connecting the Gateway District at 11th and Mississippi streets with Downtown Lawrence about 10 blocks to the east has been a priority for the city and downtown merchants who want make it as easy as possible for convention-goers to make their way downtown for shopping and dining.

The agreement, section 8.6, says KU, the hotel operator and downtown Lawrence businesses shall collaborate to provide a “regular transportation service between the project and downtown Lawrence at no cost to the city.”

— City guarantee. Most of this incentive package doesn’t come with a guarantee from the City of Lawrence. One part of the package, however, might. The incentive package includes a tax increment financing district. The TIF would capture new property tax revenue generated on the property. While KU doesn’t pay property taxes, if a private company builds and operates a business on the site — like a hotel or restaurant or for-profit student housing — those elements would pay a property tax. The TIF would capture those new property taxes and allow the dollars to be used to pay for infrastructure related to the Gateway District.

The agreement allows the city to use that TIF district to issue TIF bonds that initially would be backed by the revenues the district creates but also would be backed by the full-faith-and-credit of the City of Lawrence. In other words, if the TIF district didn’t generate enough revenue to pay off the bonds, general city taxpayers would be on the hook to cover the shortfall.

The city’s potentially comfortable with that idea — the agreement gives the city the opportunity to issue such bonds but doesn’t require it to do so — because the city would be getting the bulk of the TIF proceeds. The TIF district is expected to generate $19.5 million in new taxes over the next 20 years. The city would get about $14.5 million of those TIF funds to pay for city infrastructure projects in the general area of the stadium, including improving the corridor between the stadium and downtown.

Importantly, the city confirmed to me that the TIF bonds are the only bonds the city is contemplating offering under the full-faith-and-credit of the city. The STAR bonds are a much bigger part of that project. I went into great detail in May about how those bonds work. In general, they allow the developers to use any new sales tax revenues generated by the project and the surrounding campus to help pay for infrastructure costs. The STAR bond is powerful because it doesn’t just capture new local sales taxes, but also captures new state sales taxes. As a result, about $40 million of the $60 million the STAR bonds are projected to provide the project would come from dollars that otherwise would go to state government. The remainder would be dollars that normally would go to local government.

But, the key point when it comes to a guarantee is that if the project produces less sales taxes than projected, the City of Lawrence isn’t on the hook for any bonds that were counting on those sales tax proceeds. The city is not agreeing to use its full-faith-and-credit — also known as its taxing authority — to back any STAR bonds, a city spokeswoman told me.