Leader of Kansas public defender office resigns in face of budget cuts, constitutional crisis

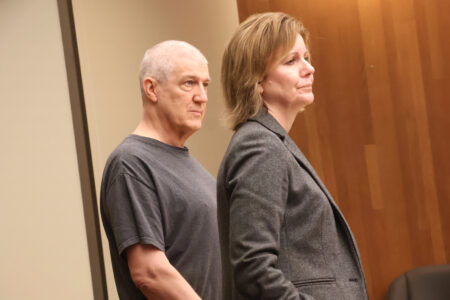

photo by: Sherman Smith/Kansas Reflector

Heather Cessna, former executive director of the Kansas State Board of Indigents’ Defense Services, appears at a June 26, 2025, recording of the Kansas Reflector podcast.

TOPEKA — Heather Cessna is resigning as executive director of the state public defender’s office after years of warning apathetic legislators about the constitutional crisis they created by persistently underfunding her agency.

Cessna said the Legislature’s refusal to adequately support public defense work will result in criminal cases being dismissed because there are no attorneys available to represent impoverished defendants.

“It is not a question of if it will happen,” Cessna said on the Kansas Reflector podcast. “It is a question of when and where. And I can tell you we are on the verge of that every single day in every jurisdiction.”

Friday was Cessna’s last day at the Board of Indigents’ Defense Services, the public defense agency she has led since October 2019. She is preparing to join the faculty at Washburn University School of Law.

Cessna has appeared annually before the Legislature to warn lawmakers of the inherent constitutional crisis they created by underfunding public defense for 30 years — while prosecutors have enjoyed unchecked power to file more and more criminal cases, she said.

Lawmakers have refused to add sufficient resources to Cessna’s budget. This year, they responded to her call to action by cutting her budget by 1.5%.

The U.S. Constitution guarantees defendants the right to legal counsel and a speedy trial, and 84% of adult felony cases in Kansas require appointed counsel.

Cessna’s agency employees 300 workers, including defense attorneys, mitigation specialists, investigators and legal assistants. Her office also provides administrative oversight for the 350 private attorneys who are willing to be appointed to cases. Combined, they are expected to handle 30,000 criminal cases per year, Cessna said.

“One of the most frustrating parts of the legislative session this year was sitting through some of our budget hearings, where individuals who I’ve had this conversation with over and over again, who we’ve filed testimony in front of, we filed reports in front of, we’ve been very clear at every step along the way that we are in a constitutional crisis right now,” Cessna said. “And the fact that we’re holding it together with duct tape and bubble gum doesn’t mean that it’s less of a constitutional crisis.

“And yet, there were conversations during our budget hearings about how, ‘Well BIDS is not in a constitutional crisis right now. So how is the impact of this budget decision gonna put them in a constitutional crisis next year?’ And it was about all I could do to keep from coming unglued during that conversation, because I don’t know how much more clearer I could be about it.”

Her cries for help were underscored earlier this year when the Deason Criminal Justice Reform Center at Southern Methodist University in Texas released a 23-page report on the public defense crisis in Kansas. The report highlighted the “dire shortage” of public defenders, work stress caused by high caseloads, and the likelihood that the crisis is about to worsen.

The report found that public defenders in Kansas handled an average of 170 cases per year. If they worked 40 hours per week for all 52 weeks of the year, they would spend an average of 12 hours on each case.

“As a result, people accused of crimes in Kansas face tough choices,” the report concluded. “Will they languish in jail, waiting for their attorney to have time to defend them? Will they consider pleading guilty despite possible defenses, risking incarceration, fines, and a loss of rights, just to put the criminal court process behind them?”

Cessna put it this way: “It has turned into a system where we tend to triage cases instead of actually representing people.”

She said the standard to provide minimally competent counsel for a low-level felony case is 33 hours per attorney. The minimal standard for a first-degree murder case would be 240 hours, she said.

“So 12 hours is absolutely a crisis, and that’s one of the reasons why we have repeatedly gone over and asked for additional staffing from the Legislature,” Cessna said. “Because the truth of the matter is we’ve got too many cases coming in to these jurisdictions, they’re being charged, and we don’t have the number of staff that we need to be able to support those caseloads.”

She said lawmakers have been unwilling to support public defense in part because “our clients are not the most popular people, and it is not usually a popular topic to add money into criminal defense.”

“Now, I will counter that by saying that the vast majority of our clients are presumed innocent, and that’s an important thing to remember when we’re talking about public defense,” Cessna said. “These are people who have not been convicted of a crime.”