Acclaimed author behind ‘Death by Lightning’ shares some thoughts on the ‘soap opera’ of human history ahead of Baker visit

photo by: Contributed

Best-selling author Candice Millard is scheduled to speak Sunday, Feb. 22, at Baker University.

If you thought we lived in the Information Age with 24/7 news, the internet, social media and AI, consider the fact that in the 19th century every city of any size had a dozen or more newspapers with multiple daily editions, and people routinely wrote (and retained) loads of letters in addition to keeping diaries.

It’s a fact that has kept best-selling author Candice Millard returning again and again to people born in the 1800s — Winston Churchill, Theodore Roosevelt, James Garfield and the intrepid explorers who searched for the source of the Nile.

“My book on Garfield, I mean it took me an entire month just to go through The New York Times articles about his shooting,” she said, “because they covered it from every single angle.”

Such granular source material, along with a wealth of personal correspondence, is what has allowed Millard to write four critically acclaimed books that read like novels even though they’re 100% nonfiction.

Even the bits of dialogue that lend so much intimacy to the narratives are wholly documented.

“I make nothing up,” Millard, a former journalist and National Geographic editor, says to readers who assume the quotes must be fabricated.

“Never.”

If a conversation occurs between two Roosevelts floating down the Amazon in “The River of Doubt,” say, it’s because someone documented it at the time in a letter or a diary.

Millard notes that if she were writing about a living person (which she has no interest in doing), she might find herself scrolling through Instagram and deciphering text lingo instead of paging through a riveting diary or lively hand-written correspondence.

While Millard’s books are entirely historical, that’s not quite true of a recent cinematic adaption of her 2011 book on Garfield, America’s 20th president and the second of four to be assassinated. Dramatic films just don’t work that way, she notes, but she nevertheless loved Netflix’s hit series “Death by Lightning,” based on her 2011 book “Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President.”

“It’s true to the spirit,” she says of the film starring Michael Shannon as Garfield, Matthew Macfadyen as assassin Charles Guiteau and Nick Offerman as Vice President Chester Alan Arthur. Despite some notable but intentional anachronisms, “It stayed true to who those people were and to what happened at that moment in time.”

“I think they did a beautiful job,” she says. “I think the cast was incredible.”

photo by: Andy Kropa/Invision/AP

Author Candice Millard, left, and series creator Mike Makowsky attend the Netflix premiere of “Death by Lightning” at The Plaza Hotel on Monday, Nov. 3, 2025, in New York.

She had one request of screenwriter Mike Makowsky, which she said he honored: “I said, look, I really care about one thing, and that is Garfield’s character. I want that to come through — who he genuinely was.”

Like most of us, Millard started out not know anything about Garfield besides the fact of his assassination. She stumbled onto him because she was interested in Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone who, incidentally, used one of his “metal-detector” contraptions to help look for the bullet lodged in Garfield’s body.

“Ah, I wonder what Garfield was like,” Millard recalls thinking as she read about Bell. She did some research, “and I was just blown away.”

“You can ask my husband: I was bothering him every two minutes asking him ‘Did you know?'”

Did you know Garfield was an incredible Classicist? An incredible mathematician? That he hid an enslaved person who ran away? That he was instrumental in bringing about Black suffrage? Did you know he was a war hero? That he helped form the Department of Education because learning had been his salvation growing up poor? Did you know that he was a “poor hater” because his fundamental decency prevented him from ever holding a grudge?

She could go on — and no doubt will on Sunday, when she is scheduled to speak at Baker University, her alma mater. At the free public event she’ll discuss her Garfield work, the Netflix show, her other books and take questions from the audience. Ahead of that event, she spoke to the Journal-World this week about a variety of topics, including how she became a writer and the appeal of history.

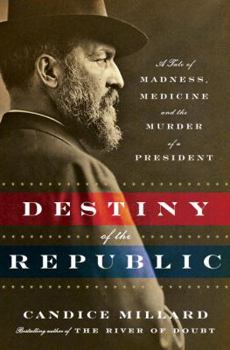

photo by: Contributed

Candice Millard’s “Destiny of the Republic” is the basis for Netflix’s “Death by Lightning.”

‘Something small’

Millard, 58, made her way to the Kansas City area, where she still lives, as a teen when her dad got a job with Sprint and moved the family from Lexington, Ohio.

“You can imagine moving right before your senior of high school,” she says, especially to a large suburban high school like Shawnee Mission Northwest. “I didn’t know anybody.”

But that period of feeling uprooted and solitary is “actually when I started writing.”

A kind of average student before, she decided to start studying and took a class in journalism. A teacher suggested that she write for the school newspaper, and before long she wound up with a journalism scholarship to Baker University.

“I wanted something small again,” she said of the private school in Baldwin City, a town approximately the size of her native Lexington.

After Baker, she went to grad school at Baylor and thought about an academic career teaching literature until, like many an English major, she realized she hated literary criticism.

“I just loved to read,” she says. “So I dumped it all and moved back to Kansas City … and tried to get a job working for a magazine or something.”

The magazine she eventually landed a job with was National Geographic. There, she covered a variety of natural and scientific topics, but ultimately she became a kind of point person for stories involving biography and history.

“What I realized is, I loved human stories,” she says. “It was always a human story that stayed with me.”

Another realization she had is that writing is a “meritocracy.”

“When I was at National Geographic, most of the people I worked with, my friends, went to Harvard and Princeton and Yale. I went to Baker, which — I got a great education there — but nobody had heard of it, right? But it didn’t matter where I went to school. It didn’t matter who my parents were. …What mattered is if I could write.”

‘A gateway drug to history’

The kind of story-telling she became intensely interested in was not birth-to-grave biography but “a moment in somebody’s life that I think is really illuminating about them” – like Garfield’s unlikely election to the presidency and his assassination just a few months later; Churchill’s prison escape during the Boer War; Roosevelt’s mapping expedition on the Amazon River; and the toxic relationship between explorers Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke as they searched for the Nile’s source.

“Basically, history is a soap opera,” Millard says, and a deeply engaging one at that, countering the notion that it’s a collection of dates and names — or even that it’s in the past, really.

“People, forever, have the same feelings that we have, the same experiences that we have, any time in history, they experience envy and hate and astonishing generosity and triumph and tragedy and ambition and betrayal and all those things. And that’s fascinating.”

“There’s so much more there,” she says, “and that’s why I always think of narrative nonfiction as a gateway drug to history.”

Each of Millard’s books has involved several years of deep digging.

“Probably 80% of the process is research,” she says, and that, happily, has involved a lot of travel — to places like the Amazon River Basin, the Nile Valley, South Africa and Tanzania.

Her next book, which she’s in the process of writing now, took her to castle-dotted regions of Belgium and Northern France. Set in the first year of World War I, it’s the true story of women who helped Allied soldiers who were left behind — and in danger of being killed — following battles in German-occupied territories.

The book won’t be published for another year or so, but when it is, Millard hopes it will be a reminder that “history is really, really interesting, and history is us.”

Millard will appear at 3 p.m. Sunday in Rice Auditorium at Baker University in Baldwin City. The event is free and open to the public, but reservations via the Baker website are encouraged.