Citing historic map, Pinckney Neighborhood resident believes controversial namesake was meant for someone else

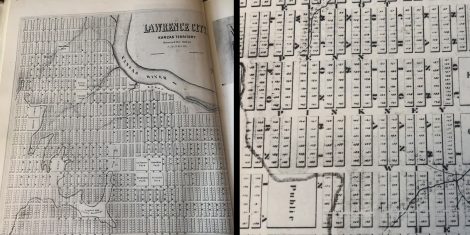

photo by: Dylan Lysen/Lawrence Journal-World

A map published in "Pictorial History of Lawrence," left, shows the original plan for Lawrence, mapped by A.D. Searl, while a close-up of the map, on the right, shows the street previously known as Pinckney Street and is now known as Sixth Street spelled as "Pinkney."

Updated at 10:41 a.m. Monday, Jan. 25

As discussions began last year around a Lawrence neighborhood and elementary school that both use a name that reportedly honors a South Carolina slave owner, a longtime resident knew a bit of history was missing from the conversation.

Tom Krause, who has lived in the Pinckney Neighborhood since 1981, thinks the name may not actually refer to the slavery advocate.

Instead, he thinks the name, which ostensibly honors Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, was actually spelled differently when it was first used for the street that is now known as Sixth Street, suggesting that the settlers of Lawrence meant to honor a different man. That man is William Pinkney, a former U.S. attorney and Maryland statesman who argued against the institution of slavery. That information was provided to the Pinckney Neighborhood Association’s name committee in July by resident David Unekis, according to the association’s meeting minutes.

With this information, Krause told the Journal-World that the Pinckney Neighborhood, which is undergoing a name change, could drop the letter “C” from its name to revert to what he thinks was the original.

“He was a good guy; he was against slavery,” Krause said of William Pinkney. “If you look at the maps and everything, I think the name got co-opted in the name of racial insensitivity.”

Although Krause is correct that there is evidence of a different spelling of the name, it’s almost impossible to tell which one was the original. But two local historians and the Lawrence city clerk think there may not be much controversy. They told the Journal-World recently that the map Krause referred to may have included a simple map-making error.

“My guess for the reason behind that is map-maker’s misspelling,” said Steve Nowak, executive director for the Watkins Museum of History. “Don’t they say the simplest reason is usually the right one?”

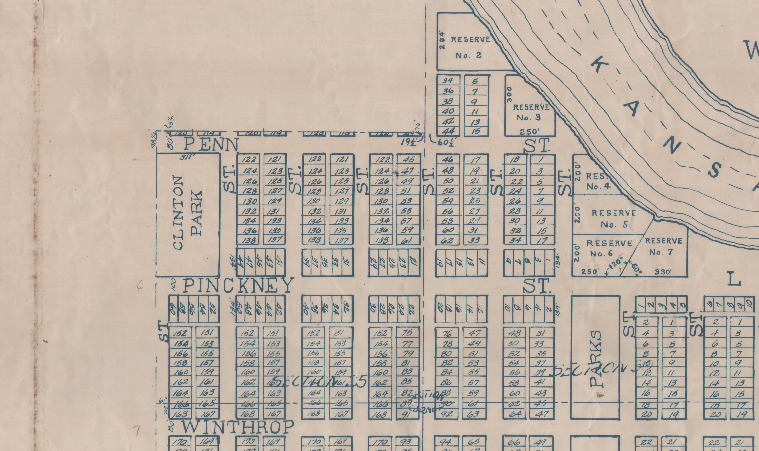

photo by: Dylan Lysen/Lawrence Journal-World

A close-up of a map of Lawrence published in “Pictorial History of Lawrence and Douglas County” shows Pinckney Street, which is now known as Sixth Street, spelled as “Pinkney.”

Pinckney Elementary School and the Pinckney Neighborhood both got their name from the street they are located on. When Lawrence was first settled, the street was known as Pinckney Street, but it was renamed in the early 1900s to Sixth Street.

While the school and the neighborhood both thought the name was meant to honor Charles Cotesworth Pinckney — an American Revolutionary War veteran and signer of the U.S. Constitution, as well as a slave owner and slavery advocate — Krause said an early Lawrence map he found in the book “Pictorial History of Lawrence” shows the street was originally spelled as “Pinkney.” The book notes the 1854 map was the first plan for the city that would become Lawrence, made by a man named A.D. Searl.

Previous coverage

• Jan. 2 — Pinckney Neighborhood working toward changing name that comes from South Carolina slave owner

Nowak said a similar map made by Searl is the earliest map of Lawrence he is aware of, showing the spelling as “Pinkney” as well. That map was made sometime between 1850 and 1880, according to the Kansas Historical Society.

Krause said he thought Searl’s map might be proof that the street was meant to be named for William Pinkney because of his anti-slavery stance. He said his research shows Pinkney in the late 1700s made an impassioned speech about abolishing slavery, which would later be made into a pamphlet and used by abolitionists to support their cause.

According to “Dictionary of American Biography” in the Maryland state archives, Pinkney made this speech to the Maryland General Assembly in 1789. He would later go on to serve as the U.S. attorney general, then in Congress for Maryland, both as a House representative and a senator.

But while serving as a U.S. senator, Pinkney’s history on the slavery issue would become more complicated. Pinkney was instrumental in developing the Missouri Compromise, an 1820 federal law that allowed Missouri to become a state that allowed slavery. His biography notes this is when the pamphlet from his 1789 speech was made, passed around in Congress by Quakers who wanted to challenge Pinkney’s support of Missouri’s statehood, which ultimately made him “the champion of the slave-holding states.”

But Nowak said he did not think the street was meant to honor William Pinkney. He previously told the Journal-World the city’s plan was developed in Boston, where there is a Pinckney Street. He said the chosen spelling by Searl could have easily been a mistake. He noted that another map, published in 1873, shows the street name spelled as “Pinckney.”

“I believe its name has always been spelled with a ‘C,'” Nowak said. “Perhaps the school’s founders didn’t pay close attention to the spelling of the street’s name, or the city changed the spelling around 1870, or we are all victims of a map-maker’s error.”

The Douglas County Register of Deeds Office also has evidence that the street was meant to be spelled with a “C.” Register of Deeds Kent Brown provided the Journal-World with the earliest map his office holds, which also shows the street spelled as “Pinckney.”

photo by: Contributed photo/Douglas County Register of Deeds

The earliest map in the possession of the Douglas County Register of Deeds Office that refers to Pinckney Street shows the street name spelled with a “c.” Register of Deeds Kent Brown said he is not sure when the map was made, but said it includes a note that it is a copy of the original plat of Lawrence, which was believed to have been lost during William Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence in 1863.

Although Brown said he was not sure when the map was made, he said it includes a note that it was created as “a copy” of the original plat of Lawrence. The original was believed to have been lost in William Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence in 1863. Brown said he thought that the map would have been made shortly after the raid, as it would have been a document in high demand for the county, but that he could not be certain.

Additionally, Steve Jansen, who is a former director for the Watkins Museum and served as editor for the book Krause referenced as evidence, also thought the street was meant to be spelled as “Pinckney.” When reached by the Journal-World, Jansen said the street was named for Pinckney and Searl’s spelling was an error.

Spelling errors on old documents are also fairly common, said Sherri Riedemann, Lawrence city clerk. While she did not provide the Journal-World with an official map, she said she would not be surprised if Searl’s spelling was a mistake.

“Many documents, minutes, charters, resolutions, orders, etc., were handwritten in cursive and are very hard to read,” Riedemann said in an email. “The proper spelling was lost in translation quite often.”

Regardless, Krause said he thought changing the neighborhood name to Pinkney could be a compromise for those who don’t believe changing the neighborhood name is necessary. It would also honor someone who once argued against slavery, which would better align with Lawrence’s abolitionist past, he said.

But that name is not something he is dead set on, he said. He thinks the neighborhood would be better off choosing something “noncontroversial.”

The Pinckney Neighborhood Association said it has already received multiple suggestions that reference the neighborhood’s proximity to the Kansas River. Krause said choosing a name referencing the neighborhood’s geographical location might be better than naming it after people who may have complicated histories.

“If we want to change the name, I would be happy if ‘river’ was in there somewhere,” Krause said. “That would be, in my opinion, noncontroversial in the future.”

Editor’a note: This story has been updated to include information provided to the Pinckney Neighborhood Association’s name committee in July by resident David Unekis, according to the association’s meeting minutes.

Contact Dylan Lysen

Have a story idea, news or information to share? Contact reporter Dylan Lysen:

- • dlysen@ljworld.com

- • 785-832-6353

- • Twitter: @DylanLysen

- • Read other stories by Dylan