Lawrence NAACP pushes for memorial at site where three black men were lynched in 1882

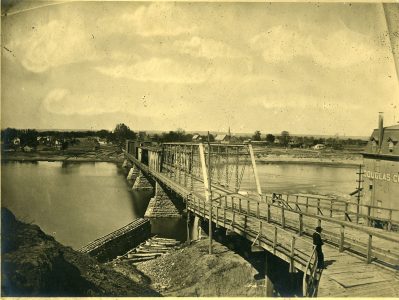

photo by: Watkins Museum of History

The old bridge across the Kansas River near downtown Lawrence is pictured in 1866. The bridge was used to lynch three black men in 1882.

After Pete Vinegar was lynched at the Kansas River bridge near downtown Lawrence, the body of the Lawrence man — believed to be a former slave who left the South with his family — was taken down and buried in the potter’s field.

Vinegar’s interment record contains little more than his name and four words under the cause of death: “Hung by a mob.” Though Vinegar and the two other black men lynched with him in 1882 lie in unmarked graves and the old wooden bridge the lynching mob hanged them from is gone, a local group wants to make sure their deaths are remembered.

The Lawrence chapter of the NAACP is working with the Equal Justice Initiative, which created a national lynching memorial in Montgomery, Ala., to erect a historical marker with information about the lynching. Kerry Altenbernd, chair of the NAACP History Committee working on the effort, said the intent of creating a marker — to paraphrase Martin Luther King Jr. — is to help bend the long arc of the moral universe a little bit more toward justice for the three men who were lynched.

“These men were never given justice,” Altenbernd said. “They didn’t get justice in 1882; they didn’t get justice in the 137 years since then.”

In the summer of 1882, the body of David Bausman, who was white, was pulled from the Kansas River, according to newspaper and other local archives reviewed by the Journal-World. Vinegar, Isaac King and George Robertson, all of whom were black, were arrested in connection with the murder, as was Vinegar’s teenage daughter Margaret “Sis” Vinegar. Vinegar, a widower raising several children, was never charged with a crime. Before a trial could be held, Vinegar, King and Robertson were lynched by a mob of men who broke into the jail in the middle of the night.

The Lawrence NAACP History Committee has been working formally on the historical marker project for the past several months. The goal is to erect a marker on the bank of the Kansas River where the lynching occurred.

Reconciling a lynching

For some, a lynching is hard to fit within the narrative of Lawrence, which was settled by abolitionists and the headquarters of the movement to bring Kansas into the Union as a free state. But those involved with the project say telling this story is important.

Ursula Minor, president of the local NAACP chapter, said a man who recently joined the Lawrence NAACP was surprised when he heard that there had been a lynching in Lawrence. She said that it’s important that the community talk about the uglier chapters of its past.

“People say that could never happen here,” Minor said. “That’s why I think it needs to be talked about, to know that we did have a past, we did have a history.”

That past that Minor refers to was recounted in newspapers and was the subject of multiple editorials, letters to the editor and other correspondence. Those accounts say that at 1 a.m. on June 10, 1882, a mob of men with nooses in hand arrived at the jail, which was located in what is now Robinson Park, and demanded that the sheriff hand over the inmates. When the sheriff refused, the men used sledgehammers and chisels to break into the jail. The mob then cut the locks off the jail cells and pulled the men out. The mob took a vote on whether Margaret should also be hanged, and decided against it.

Newspaper accounts say that hundreds of residents gathered, but that members of the lynching mob surrounded the area so no one could interfere. The mob, some wearing masks and others with their faces blackened with ash, marched the men to the bridge, secured the ropes to the wooden trusses and threw them over. Their bodies hung from the bridge all night and were taken down the next morning.

The Watkins Museum of History has an exhibit on the Jim Crow era in Lawrence that mentions the lynching, and notes that many in Lawrence were appalled at what had taken place. Brittany Keegan, curator and collections manager at Watkins, said the event is indeed part of the collective memory of the town. Keegan, who is also a member of the committee, said that when oral histories were recorded in the 1970s, many of the people interviewed said they had been told when they were young that there had been a lynching at the bridge. However, Keegan said that only goes so far.

“It is something that is known within the community, but I don’t think it’s something that has been discussed,” Keegan said. “Or there hasn’t been an effort to reconcile it with the larger aspects of Lawrence’s history.”

Keegan said the museum has one of the nooses used for the lynching, but it is not on display. She said if the museum were to incorporate it into an exhibit, it would need to be in the proper context and not as a spectacle.

A story left untold

Accounts of Bausman’s murder in historical documents are varied, but they seem to agree that Bausman, who was in his mid-40s, had been having sex with Margaret, who was only about 14, when King and Robertson came upon the scene and allegedly killed him. Several accounts say Margaret yelled at the men not to kill Bausman. Accounts, however, disagree on the motive for the crime.

One account holds that King was in a relationship with Margaret, and that he and Robertson followed Margaret and Bausman after seeing them cross the bridge. When the men found the pair having sex, the account goes, King struck Bausman in the head, and King and Robertson ultimately killed him. The other explanation, and the one more touted by newspapers at the time, was that King, Robertson and Margaret conspired to rob Bausman, and that Margaret had lured him to the secluded spot under the bridge to aid in the robbery. Vinegar was reportedly out of town at the time of the murder, but it is thought he was possibly taken into custody along with King and Robertson because they were arrested at his house.

Though she was not hanged, Margaret did not escape an early death. She was tried for murder, and the jury convicted her. However, her defense attorney, John Waller, argued there was no evidence that she conspired with King and Robertson to rob Bausman. In 1888, Waller was attempting to gain a pardon for Margaret and had secured letters stating that her behavior was good and that she was “reformed.” However, those same letters noted she was ill. Margaret would die from tuberculosis in the state penitentiary at the age of 21, before any pardon was approved.

Altenbernd said Margaret was convicted because of racial prejudice at the time, and that the lynching makes it hard to know the circumstances surrounding the murder because the two men never had a chance to testify. He said what is known for sure is that the men did not get their day in court, and Vinegar hadn’t even been charged at all.

“The truth of something like that may never actually come out,” Altenbernd said. “But it doesn’t matter, really, in the long run because the men didn’t get a chance to go to trial.”

Next steps

photo by: Rochelle Valverde

Part of the old bridge across the Kansas River remains on the riverbank near downtown Lawrence. The old bridge was used to lynch three black men in 1882. Pictured Sept. 26, 2019.

The Equal Justice Initiative has compiled a report of thousands of lynchings committed across the country, including the three in Lawrence. As part of its Community Remembrance Project, the initiative works with communities that wish to install historical markers, producing and shipping the markers at no cost to the community. In order to be part of the program, the community must form a coalition, conduct research about the lynching victims, facilitate a racial justice essay contest for high school students, and plan a dedication and unveiling ceremony. The coalition will work with the initiative to develop the text for the marker.

Minor, who grew up in Lawrence, said that when she was in school, the lynching and other negative events were not talked about and that instead the experience of black residents in Lawrence was presented positively. She said such events need to be reconciled as a community, especially given recent divisiveness and events that have been happening in the U.S. and worldwide.

“We’re going backward, with the things that are still happening today,” Minor said. “I feel like the only way to get people together is to talk about it. With all our projects we want reconciliation, where we have a community conversation and talk about it.”

Minor said the Lawrence NAACP has been working with city staff as it develops potential plans for the marker. She said the first choice for locating the marker is near the riverbank in an area on the west side of City Hall. She said the marker would be within sight of a stone pillar, still standing today, that was once part of the bridge used to hang the three men.

The NAACP is scheduled to give an initial presentation on the project to the Lawrence City Commission on Oct. 15. The commission will not vote until a later meeting whether to approve the location for the marker. Minor said the hope is to have the marker installed in June 2020.