Former Sen. Tom Harkin given 2017 Dole Leadership Prize

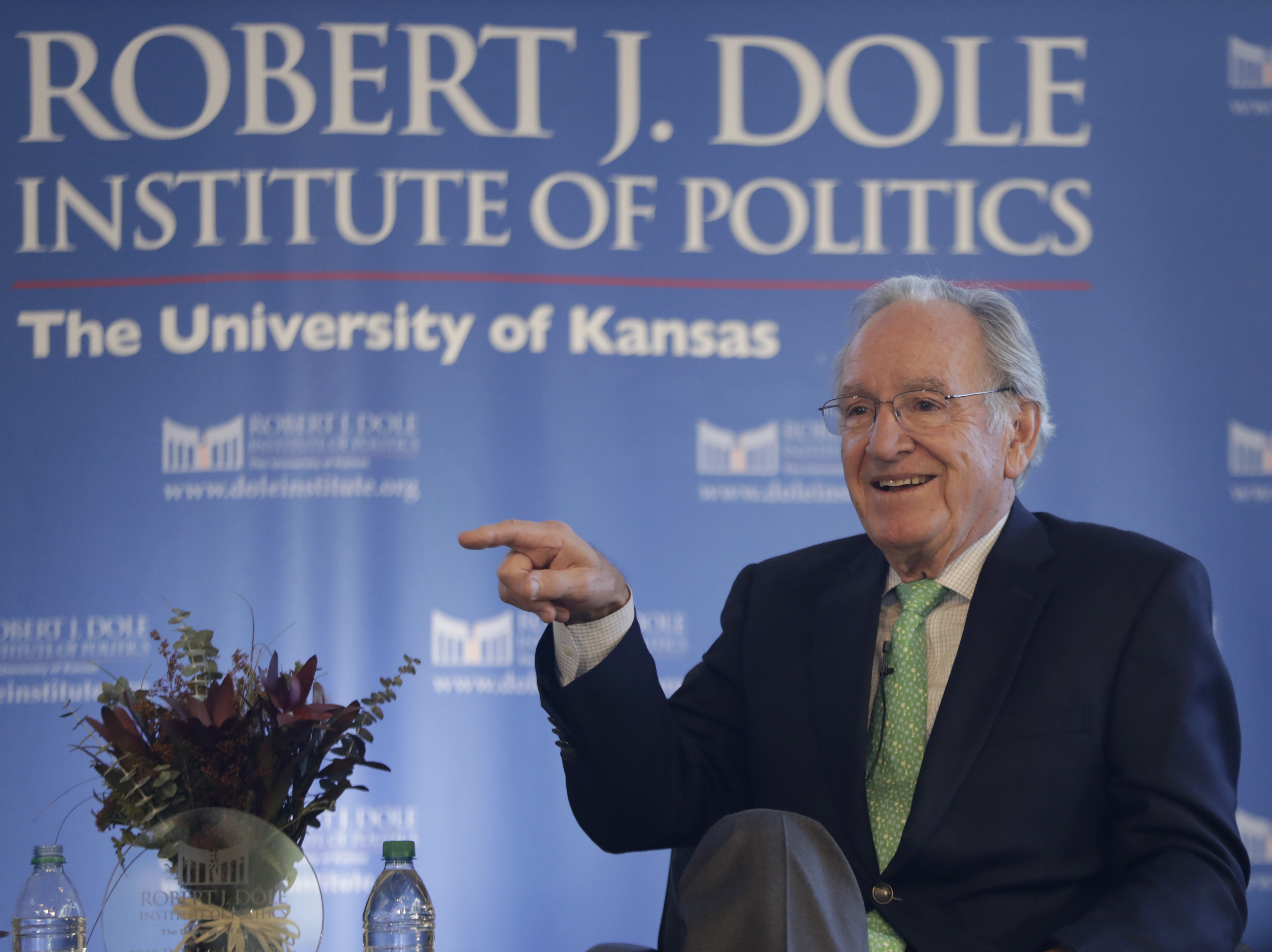

Bill Lacy, director of the Dole Institute of Politics at the University of Kansas, interviews U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin, whom the institute selected for its 2017 Dole Leadership Prize, on Sunday, Oct. 29, 2017. Harkin represented Iowa in the U.S. Congress for more than four decades, including 30 years as a U.S. Senator.

As he was honored Sunday with the 2017 Dole Leadership Prize, former U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin said the kind of relationship he had with former Sen. Bob Dole was sorely missing in the Washington, D.C., of today.

The Iowa Democrat, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1975 to 1985 and the U.S. Senate from 1985 to 2015, told those gathered at the Dole Institute of Politics that he, a liberal Democrat, and the Republican Dole were able to work together for the 11 years they served together in the Senate, despite political differences.

“We were friends,” he said. “We talked to each other. You don’t have to be an enemy because you disagree on policy.”

The Dole Institute presented U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin with the 2017 Dole Leadership Prize Sunday, Oct. 29, 2017 at the Dole Institute of Politics at the University of Kansas. Harkin represented Iowa in the U.S. Congress for more than four decades, including 30 years as a U.S. Senator. As a young senator, Harkin crafted the landmark legislation that would become the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). His long career focused on issues related to health care access and nutrition, farm policy, labor issues and more.

Dole interceded on Harkin’s behalf on the day the latter was sworn into the Senate by directing the chamber’s security to allow a sign language interpreter to remain standing in the gallery so his deaf brother could follow the proceedings, Harkin said.

“That kind of gets at your heart,” he said. “I had a very high opinion of Bob Dole after that.”

That action presaged the two senators’ cooperation in passing the Americans with Disabilities Act, which he introduced, Harkin said. He also gave credit to the actions of disability rights activists, particularly a protest at which about 15 disabled individuals got off their wheelchairs and crawled up the Capitol’s steps. Eight-year-old Jennifer Keelan’s efforts to crawl up the step, and her vow in front of network cameras to ” … take all night if I have to,” forced the House to take action on the bill, he said.

“Nobody could oppose it after that,” Harkin said. “About 30 days later, we got the bill through the House.”

The Dole Institute of Politics selected Harkin for the prize because of his work on the ADA and his efforts to advance bipartisanship and civil discourse.

Harkin also recalled working with Dole on farm credit legislation in response to the 1980s farm crisis. He contrasted his relationship with Dole with the one he had with Sen. Jesse Helms, a North Carolina Republican, who was the chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee during the crisis. In one committee meeting Dole chaired in Helms’ absence, Harkin said he called Dole “the real chairman” in a bid to get his attention.

The Dole Institute presented U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin with the 2017 Dole Leadership Prize Sunday, Oct. 29, 2017 at the Dole Institute of Politics at the University of Kansas. Harkin represented Iowa in the U.S. Congress for more than four decades, including 30 years as a U.S. Senator.

“It was no secret Jesse Helms and I never got along,” he said. “This got back to Jesse, who read me the riot act later on. When I spoke to Bob later, he said, ‘I didn’t think that was going to go over well. I’ll call him.’ He was a natural leader, able to get Democrats and Republicans together.”

He and Dole believed in cooperation for the good of the country and embraced bipartisanship to realize policy goals, Harkin said.

“He was a great legislator, because he was willing to compromise,” Harkin said of Dole. “That’s probably a dirty word today.”

Harkin said a number of things have undermined bipartisanship, starting with the need for senators to constantly chase money for re-election bids. Senators used to have joint meals on Monday in a small Capitol dining room reserved just for them, he said. The meals allowed senators to develop relationships, he said.

“There’s nobody there on Mondays anymore because they are out chasing dollars,” he said. “Tuesday is for party caucuses. Wednesdays and Thursdays are reserved for lunch fundraisers. You don’t have time to form those kinds of relationships anymore.”

Increased party orthodoxy has also undercut bipartisanship, Harkin said. When he arrived in the Senate, there were still conservative southern Democrats and moderate and liberal Republicans like Lowell Weicker, of Connecticut, Mark Hatfield, of Oregon, and John Danforth, of Missouri, Harkin said. Having different views within the party made legislators more open to compromise, he said.

The disappearance of formal political discourse has also contributed to polarization, Harkin said.

“We had debates on the Senate floor,” he said. “One great debate partner I had was Phil Gramm, of Texas. We would have debates where we go back and forth. You never see that happen anymore. Everybody gives a speech and walks off the floor.”