A look at the 10 Kansas inmates on death row

Ten inmates in Kansas are currently on death row. Those inmates are, top row from left: Kyle Flack, Frazier Cross, James Kahler, Justin Thurber, Gary Kleypas; bottom row from left: Scott Cheever, Sidney Gleason, John Robinson, Johnathan Carr, Reginald Carr.

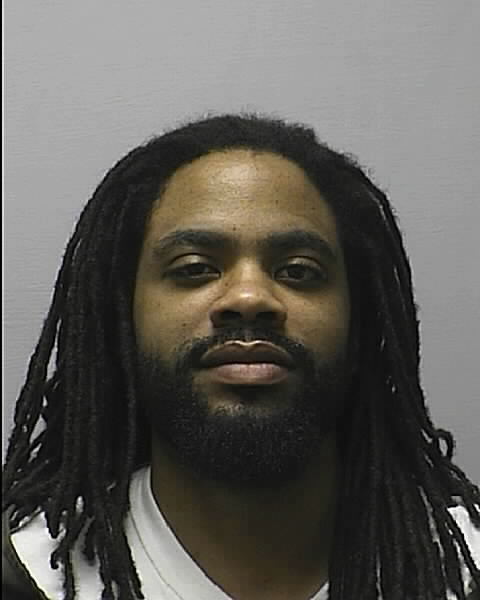

As the U.S. Supreme Court gears up to hear two cases challenging the death penalty, Kansas’ most recent addition to death row, Kyle Trevor Flack, joins the nine other inmates who have been awaiting death by lethal injection, some for more than a decade.

Flack, of Ottawa, was convicted in March of capital murder for shooting to death a toddler and her mother; he was also convicted of first-degree murder in the deaths of two men.

Kansas has not put anyone to death since 1965. That year the state hanged four men, George Ronald York and James Douglas Latham who had been on a cross-country killing spree, and Perry Edward Smith and Richard Eugene Hickock for the infamous Clutter family murders.

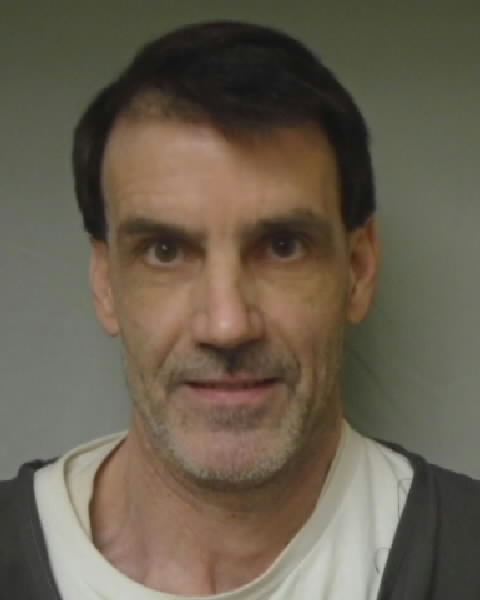

Kyle Trevor Flack

Up until 1965, all capital murderers had been hanged except one, John Coon, who was executed by firing squad in 1853.

In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively instituted a moratorium on Kansas’ death penalty along with that of three dozen other states in Furman v. Georgia. That moratorium was lifted in 1976. And in 1994, Kansas statute re-established the death penalty, this time by lethal injection.

Chances are that Flack, serving his time at the El Dorado state penitentiary, and his fellow death-row inmates will spend many more years in prison as their legal battles continue to wend their way through the courts.

So what is life like on Kansas death row?

First of all, Kansas doesn’t actually have a death row. Inmates sentenced to death are held in “solitary confinement,” which the penal system calls administrative segregation, said Adam Pfannenstiel, spokesman for the Kansas Department of Corrections.

Most of the cells are 83 square feet — about the size of a small bedroom — and have concrete walls and floors, one small window and a solid door so that inmates are unable to look through bars to visit with other inmates.

The bed is a concrete slab or metal, covered with a thin plastic mattress. Metal shelves with a sink and an attached backless stool are located along part of one wall. A metal toilet is adjacent.

Each cell has a telephone, but calls can be expensive, Pfannenstiel said. Currently in Kansas state prisons, collect and prepaid collect calls cost 18 cents per minute, while debit calls cost 17 cents per minute.

The cost of telephone calls is expected to be reduced over the next couple of years. The Federal Communications Commission issued an order in October that would reduce the price to 11 cents a minute for debit and collect prepaid calls.

Inmates may have a list of up to 20 individual phone numbers that they can call. All conversations except with the inmate’s attorney are subject to monitoring.

Cellphones are considered contraband, and only certain digital devices considered learning tools are allowed, Pfannenstiel said.

“They are able to have certain types of property, puzzles, literature, pen and paper,” he said.

Inmates can receive books from the prison library.

Inmates can earn television privileges, but they must pay for their own television and hookups out of their own funds. Cable is available but no premium channels, Pfannenstiel said.

They receive the same food as all inmates, but it is served in their cells.

“Food is brought to them and put through a sally port,” Pfannenstiel said.

Death-row inmates stay in their cells 23 hours a day, except when they have visitors, which is limited to Saturdays, Sundays and special holidays.

Visitors must be on a special list monitored by the Department of Corrections.

During the visit the inmate is placed in what is called a noncontact video-visitation booth, where a telephone-type device is used for talking while a screen displays video of the individuals, Pfannenstiel said. The Kansas Department of Corrections monitors all those discussions.

In some states death-row inmates have been able to marry.

For example, in Texas there is a practice called proxy marriage. The inmate signs an affidavit that allows him to marry without being present at the ceremony, which has raised the specter of benefits and insurance fraud in that state.

But Pfannenstiel said no Kansas death-row inmates have gotten married.

“We haven’t had any wedding ceremony,” he said.

Inmates have one hour outside of the cell each day to shower or to exercise in an outdoor recreation cage made of wire grates that is 10 feet wide, 20 feet long and 10 feet high.

The following is a list of the nine inmates besides Flack who have been sentenced to death:

Jonathan Daniel Carr

Reginald Dexter Carr, Jr.

Reginald Dexter Carr Jr., 38, and brother Jonathan Daniel Carr, 36, were convicted in 2002 for the “Wichita Massacre,” a weeklong spree of random robberies, rapes and murders. During the spree they robbed a man, seriously wounded a cellist and librarian who later died, and then shot five people execution style. Only one survived.

The Carrs were apprehended after a particularly cold-blooded act in which they broke into a house where three women and two men were spending the night. They forced the victims to strip and tied them up. They repeatedly raped the women and forced the five to have sex with one another.

After taking them to ATM machines to empty their bank accounts, the Carrs shot each of the five in the back of the head. But a woman survived after her hair barrette deflected the bullet. After walking more than a mile, naked, in snow, she made it to safety and, based on her information, the Carrs were captured.

John Edward Robinson, Sr.

John Edward Robinson Sr., 72, a serial killer, con man, embezzler and forger who was living in Johnson County, was convicted of two capital murders and one first-degree murder in 2003. He later confessed to killing five others, and detectives say there may be more.

Robinson maintained what appeared to be a normal life. He and his wife had four children. He was a Boy Scoutmaster, a baseball coach and Sunday school teacher. But that started falling apart when he was arrested for embezzling and spent 60 days in jail and said he had joined a sadomasochism cult and had become a slave-master.

Robinson is connected to murders that began possibly as early as 1984. He sought out women who had little money. In one case, he promised a woman with a child a job as a sales associate in Chicago. The woman disappeared, and Robinson gave a child to his brother and sister-in-law, saying the mother had committed suicide.

Police became aware of Robinson over the years as his name cropped up in several missing persons cases.

Robinson was arrested in 2000 on his farm near La Cygne. The police searched the farm and found two bodies in 85-pound drums.

Sidney John Gleason

Sidney John Gleason, 37, was convicted in 2006 in the shooting deaths of a couple. Gleason had learned that the woman who had taken part in a robbery with him in Great Bend was talking to police. He and his cousin Damian Thompson killed the man and shot the woman and kidnapped her. They took her to a secluded area where she was choked, shot and finally killed. Thompson cut a deal with police to testify against Gleason and also revealed where the woman’s body was. Thompson pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and received life in prison.

Scott Cheever

Scott Dever Cheever, 34, was in a house making methamphetamine in Hilltop when Greenwood County Sheriff Matthew Samuels and four other officers, acting on a tip, showed up with warrants for Cheever’s arrest.

Cheever hid in an upstairs room, and when he heard Samuels on the stairs, he leaned out from the room and shot him. When two officers tried to get the wounded sheriff, Cheever shot him again. He also shot at least four officers who were trying to arrest him.

Gary Wayne Kleypas

Gary Wayne Kleypas, 60, became in 1996 the first person to be sentenced to death in Kansas in more than three decades. Kleypas was convicted of killing Carrie Williams, 20, who was a student at Pittsburg State University. Kleypas had already killed by the time he met up with Williams. He had been convicted of the rape and murder of a 78-year-old woman in Missouri and received a life sentence. After serving half of it, Missouri gave him probation and transferred Kleypas to Kansas for supervision, and he was allowed to enroll at Pittsburg State.

Kleypas lived near Williams, and in the early-morning hours in March 1996, he knocked on Williams’ door. When she opened it a crack, he pushed it open and dragged her to the bedroom. After raping her, Kleypas later told police, he decided to kill her so there would not be a witness.

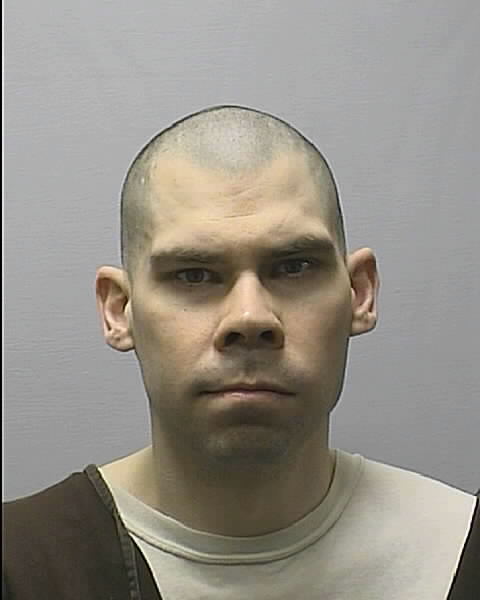

Justin Eugene Thurber

Justin Eugene Thurber, 33, was convicted in 2009 in the violent death of 19-year-old Jodi Sanderholm, who was a member of a dance team at a Cowley Community College in Arkansas City. Thurber kidnapped Sanderholm in January 2007 and took her to a wildlife area, where he tortured, raped and killed her, authorities said.

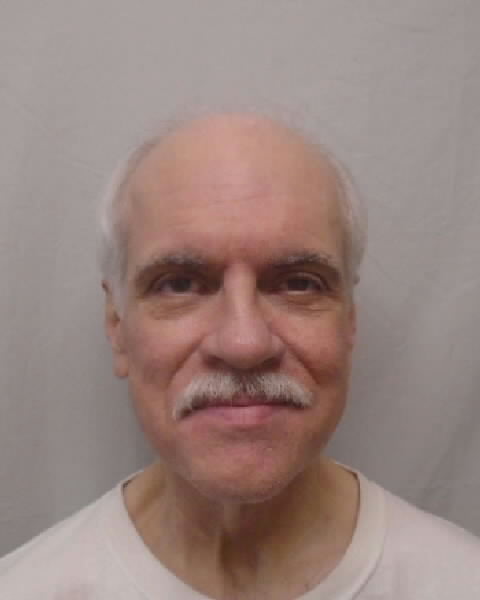

James Kraig Kahler

James Kraig Kahler, 53, was convicted in 2011 of killing his estranged wife, Karen Kahler; two daughters, 18 and 16; and Karen Kahler’s 89-year-old grandmother in Burlingame.

Kahler was upset that his wife had a lesbian lover. On Thanksgiving weekend 2009, he stormed into Karen Kahler’s house and shot her. Karen Kahler was standing next to their son, but Kahler allowed his son to flee. Then he shot the rest of the family. He was convicted of capital murder and four counts of first-degree murder.

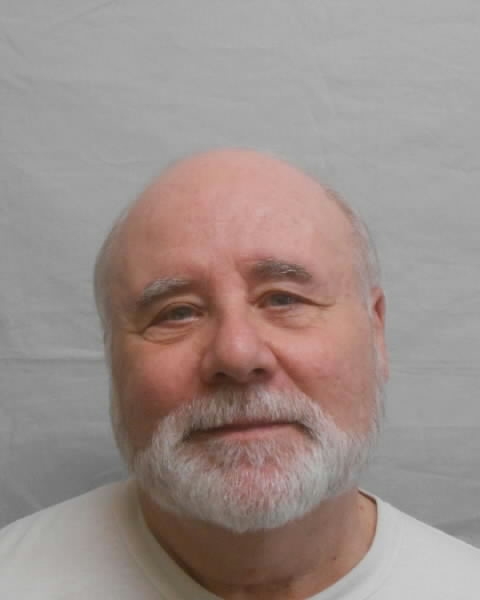

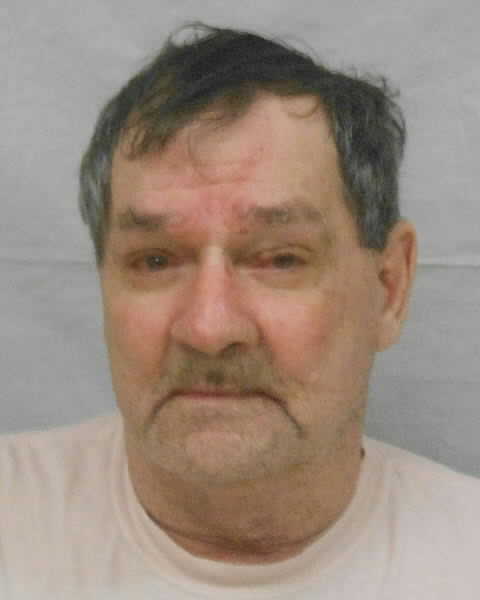

Frazier Glenn Cross, Jr.

Frazier Glenn Cross Jr. (also known as Frazier Glenn Miller), 75, was convicted in 2015 of three murders at the Overland Park Jewish Community Center and Village Shalom, a Jewish retirement community. Cross, a white supremacist, had gone on a rampage in 2014 because he said he wanted to kill Jewish people. None of the people he shot was Jewish.