Review finds Lawrence police voided city tickets without proper approvals

About 90 municipal court citations were voided by Lawrence police officers without the proper approval from supervisors, and more than 100 other tickets were canceled without going through the required procedures, a review by the Journal-World has found.

The Journal-World several months ago began reviewing how the Lawrence Police Department and Municipal Court void and dismiss tickets ranging from speeding and parking violations to battery and public urination. The review began after former Lawrence police officer Mike Monroe in August of last year lost his final appeal in a court case alleging that the city had improperly fired him for his role in a 2012 ticket-fixing scandal. That scandal involved at least one Lawrence police officer fixing traffic tickets in exchange for valuable Kansas University athletics tickets.

About these articles

In May 2011, the city began an investigation into allegations that Lawrence police officers had improperly dismissed traffic tickets for Kansas University athletic officials, who also were facing charges related to allegations of stealing more than $1 million worth of athletic tickets from KU.

Ultimately two Lawrence police officers — Matt Sarna and Michael Monroe — lost their jobs over the matter.

Monroe filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against the city. As we have reported, Monroe lost that suit against the city in August. During parts of that lawsuit, portions of the court file were closed to the public. Some court records were unsealed in 2014.

Following the dismissal of the lawsuit in August, the Journal-World assigned two reporters to begin looking in detail at the entire court file and other documents related to the case, which numbered thousands of pages. That review took multiple months. The timing of the assignment was determined, in part, by the fact that the lawsuit was no longer pending, which we hoped would make it easier for the city to respond to questions. The city routinely declines to answer questions about matters that are under litigation.

These articles explain what our reporters — Karen Dillon and Conrad Swanson — found during the course of their review.

Read the related story:Several years worth of forms detailing how police officers dismiss tickets can’t be produced by City Hall

Documents related to that court case raised questions about the frequency with which police officers were dismissing tickets and the reasons why tickets would sometimes be voided. Voiding a ticket means canceling it before it reaches the court system; dismissing it means canceling it after it has entered the court system.

As part of the review, the Journal-World discovered 88 tickets that were voided before a supervisor gave approval for the voids. The review of 927 void and dismissal forms filed by Lawrence police officers between August 2012 and 2016 found many lacked required signatures from officers or prosecutors, or were vague about the reasons why a ticket was being canceled.

An example of a dismissal form.

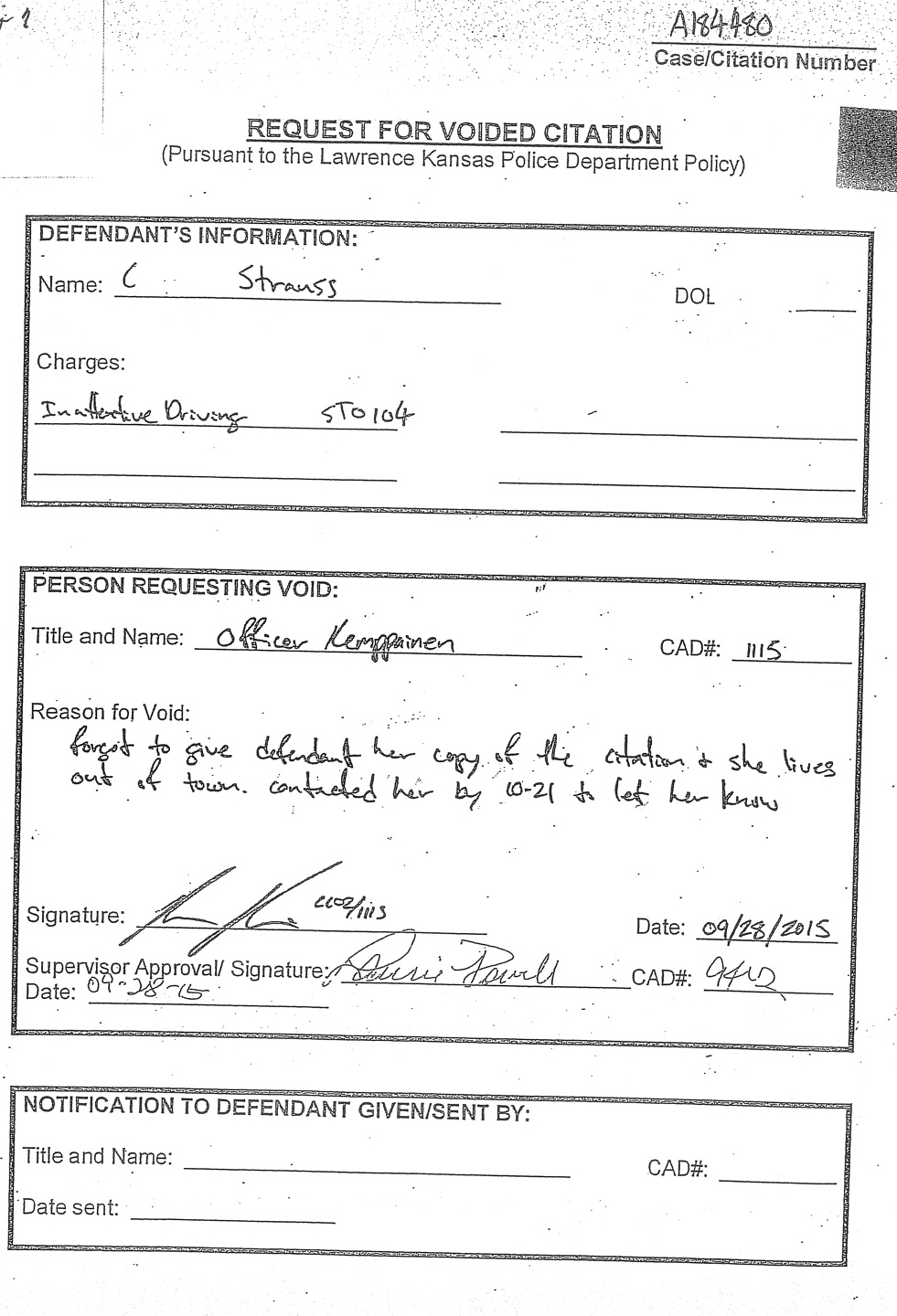

An example of a void form.

As a result of questions raised by the Journal-World, the city began a review of its current policies and has implemented several changes, including an annual audit of tickets voided.

The city also is contemplating further changes to its policies, which may include provisions that require court prosecutors to approve the voiding of tickets rather than police supervisors. Such a change would more closely align the Lawrence Police Department’s ticket-voiding policies with other area police departments such as those in Topeka and Olathe.

“We probably need to do a better job, do some deconfliction between the (police department’s) Office of Professional Accountability and municipal court,” said Lawrence Police Capt. Adam Heffley, who oversees the police department’s technical services division. “And come together and say ‘this is what I have,’ ‘this is what I have’ and go through one by one to ensure that we are getting the checks and balances that we are all looking for.”

The findings

City officials contend the forms do not show that police officers were voiding tickets based on favoritism or other factors that are prohibited by the city’s policies.

“The error(s) were those related to workflow and processing of the forms, and not related to officers unjustly requesting certain citations be voided or dismissed,” Heffley said of the 88 forms in question.

The circumstances surrounding the 88 forms are noteworthy. The 88 tickets were voided despite the fact that request forms were misplaced in a lockbox — for years in some cases — and did not receive a required supervisory signature.

Heffley said he discovered the error after the Journal-World’s request for the documents, and then signed off on the forms, although the tickets already had been voided, in some cases three years earlier. Heffley said he researched whether the reasons for the voids and dismissals were in line with city policy, and found in each instance that they were.

Lawrence Police Capt. Adam Heffley

The city did not initially disclose the fact that 88 forms were not signed by a supervisor. It was only upon further inspection by Journal-World reporters that it was noticed that many forms were signed Feb. 8, 2016, which was four days after the Journal-World had made a Kansas Open Records request for the documents.

It is unusual for a government to alter records in such a manner before turning them over as part of an official open records request. Generally, open records requests are interpreted to be a request for records as they exist on the date of the request.

City officials also heavily redacted the names of people whose tickets were voided or dismissed. The city removed either the full or partial name of each defendant listed on the forms. Because of those redactions, it is difficult to know precisely for whom officers were voiding tickets. Thirty-five percent of all forms had the defendant’s names fully redacted.

City Attorney Toni Wheeler said the names were redacted to protect the privacy of those cited. The redactions, though, inhibited a meaningful review of whether the city’s policy — meant to prohibit favoritism — is working as it should. For example, it is difficult to determine whether any citations were dismissed for city employees, elected officials or others who may have a prominent role within the community.

Diane Stoddard

Assistant City Manager Diane Stoddard provided no further information about the identities of those whose tickets were dismissed, but said the city is confident officers are not violating the city’s favoritism policy.

The Journal-World’s review also found other questionable requests. They include:

• A police officer asked that a ticket he issued to the wife of a Kansas Highway Patrol trooper be dismissed. The citation was for speeding in a school zone, 38 mph in a 20 mph zone.

“Defendant is the wife of a KHP trooper and I have no problem having the citation voided,” the officer wrote on his request.

The request to void was approved by his sergeant but a notation at the top of the form written two days later said the request was declined and returned to the officer. The request denial bears no signature or initials, and Stoddard would provide no further explanation.

Ten days after the officer’s request was denied, Lawrence Municipal Court records show that former City Prosecutor Jerry Little dismissed the citation entirely and without explanation.

When asked to explain why the ticket was ultimately dismissed, Stoddard said the city “has no records in this instance that set forth the reason the former city prosecutor dismissed the citation.”

Little did not return multiple calls seeking comment for this story.

Lawrence Police Chief Tarik Khatib

• Another officer voided a speeding ticket for a Douglas County emergency communications dispatcher. The request was approved by Police Chief Tarik Khatib in an effort to “maintain a good working relationship” between the two organizations, said Stoddard in an email. Khatib declined multiple times to be interviewed for this story or to answer any questions related to ticket voids, dismissals or the department’s policies. Stoddard said that void perhaps required additional “introspection.”

• Several tickets were voided when the officer requesting a void approved his or her own request by signing as a supervisor. The department’s policy states that any officer requesting a void must get the approval of a supervisor.

When asked why officers were able to sign their own approvals, Heffley said in an email that “many of the forms signed only by one supervisor were parking citations. While the process wasn’t carried out exactly, the reasons for the requests were justified.”

“I don’t believe that is inappropriate,” he said in an email.

Since the issue was brought to light, Heffley said in an interview that the department has clarified expectations for the requests.

“We talked to supervisors and made sure they understood the expectation, and that clarified some things about supervisor approval,” he said. “Doesn’t just mean if you’re a supervisor you can sign off. You probably should have a second layer of eyes on it, somebody else to look at that.”

When initially asked about several concerns regarding the city’s ticket voiding practices, Stoddard said in an emailed statement that the city’s policy “reflects the City’s demand for transparent and ethical operations.”

“The review of the forms shows this policy is effective and working appropriately,” she added.

Stoddard did say some of the forms raised concerns, but ultimately the city found them to be in line with the city’s policy.

How it works

The review found that 136 of 159 dismissal forms did not bear the required signature of a prosecutor. When asked why those signatures were missing, Stoddard said the officers in each instance used the wrong form to submit their requests.

When a police officer seeks to cancel a ticket, the officer fills out one of two forms. A void form is used when the ticket has not yet been sent to municipal court for processing. A void form requires only the approval of a police department supervisor. A dismissal form is used if the ticket already has been sent to municipal court for processing. It requires approval from a city prosecutor.

Stoddard said a city review determined that the 136 dismissal forms actually should have been filed as void forms, which do not require a prosecutor’s signature. She explained that the void and dismissal forms look very similar and can easily be confused.

Given that the forms look similar, the Journal-World asked how many times the remaining 768 void forms were used when a dismissal form should have been used. That potentially could be a more serious error because it could open the door for some tickets to have been dismissed without a prosecutor’s signature.

Stoddard said that for the city to answer that question, the Journal-World would need to pay a $100 fee.

“In order to answer this question that you pose, we estimate around 2 hours of staff time, or approximately $100 to fulfill the request,” Stoddard said in an email.

The Journal-World did not pay the fee. The newspaper routinely pays for reasonable costs related to copying and retrieval of records as part of an open records request. The Journal-World, in this instance, was not seeking any new records, but rather had asked the city a question. The Journal-World is prohibited by ethical standards from paying a source to answer questions for an article.

As part of the Journal-World review, the city did provide information about why tickets had been voided or dismissed. There are several legitimate reasons citations may be voided or dismissed. Through their own analysis, city officials examined the 927 forms to determine the reasons for the requests. They found:

• Officer error accounted for 252 requests.

If an officer misspells a name or an address on a ticket, the police department’s current computers do not allow the officer to correct the errors, Heffley said. As such, the tickets must be voided and a new ticket must be issued.

Other examples in this category include officers forgetting to issue tickets, citing the wrong person or handing defendants the wrong version of a ticket.

• Equipment malfunction accounted for 222 requests.

Technical difficulties with computers that are used to issue tickets may cause a citation to be inaccurate or incomplete, and therefore it would need to be voided, Heffley said. The computers are quite sensitive to temperature, and the issues may be exacerbated by colder temperatures.

• A total of 156 tickets were referred to the Douglas County District Attorney’s Office.

This often happens when officers issue citations, but upon further investigation learn a more serious crime has occurred and the matter needs to be referred to the district attorney to make a charging decision, Heffley said. District Court does not handle municipal tickets. In those cases, the municipal ticket is canceled, and charges are filed through District Court.

• Duplicate tickets accounted for 104 requests.

Once a ticket has been issued, officers may notice the person was already cited for the violation, Heffley said. This happens most often when officers don’t see a car was already issued a parking ticket until after they finish writing their own citation.

• A total of 97 requests were submitted because officers noted the violations were corrected during the stop.

This may happen if a driver was cited for driving without insurance, but after a ticket was issued the driver located his or her proof of insurance, Heffley said.

The rest of the forms are broken down into a variety of other reasons, all of which, the city said, are acceptable under its current policy.

The policy, which is available online, offers seven examples of “just cause” where officers are allowed to void or request the dismissal of a citation. That list includes voiding citations when they are not legally or factually warranted, when they would compromise an ongoing investigation, when ticket completion is abandoned because of another service call.

The final circumstance is a single sentence listed in the policy that could include almost anything, except favoritism: “Other articulable rationale in the interest of good public service and not based on favoritism,” the policy says.

The city said 14 requests since 2012 were submitted in the “interest of justice.”

“In the interest of justice relates to the department’s mission of providing good and fair public service to the community,” Stoddard said.

Other cities differ

Other police departments, including Topeka’s and Olathe’s, allow only city prosecutors to cancel tickets. With the exception of a few instances — typically with regard to equipment malfunctions — officers are entirely prohibited from voiding tickets themselves.

Lawrence officials said they likely will have discussions about whether such a policy change would be appropriate for Lawrence. But city officials also said they thought the number of tickets voided or dismissed was relatively small. The city said in an emailed response to questions that since 2012 more than 100,000 tickets have been issued and called the 927 tickets that were voided or dismissed statistically “insignificant.”

“We don’t see how this is problematic. Perception may be one thing but the reality is completely something else,” the response said.

Other cities have dealt with questions about how tickets are voided or dismissed. A 2015 internal audit of the city of Henderson, Nev., exposed issues with the city’s ticket voiding policies, including that nearly 100 tickets were improperly voided by police officers there.

Since the results of Henderson’s internal audit were released, the city has changed its ticket voiding policies to ensure more checks and balances are in place.

Jason McIlrath, Topeka assistant city attorney, said city prosecutors are responsible for dismissing or amending down any tickets. He said tickets are not voided. Instead, an agreed order is issued by the prosecutor’s office.

“I have not seen an instance where we just voided out a traffic ticket unless there is something incredibly incorrect,” McIlrath said.

For example, if an officer writes down the wrong Vehicle Identification Number, the prosecutor would still be responsible for dismissing the charge, he said.

“Other than that, there is not a circumstance where we would void out a ticket,” he said.

Sgt. Bryan P. Hill of the Olathe Police Department said police there can void tickets but only in certain circumstances such as defective equipment.

“It is not a common occurrence,” Hill said.

Jeffrey Ian Ross, a professor with the school of criminal justice at the University of Baltimore, said allowing police to void tickets gives an appearance of favoritism and can lead to unethical behavior and corruption.

“Tickets should be voided because there is evidence … that there was some error in judgment on the part of the officer or equipment malfunction,” Ross said.

Changing policies

Prior to 2005, it is not clear that the Lawrence Police Department had any written policy regarding when or why police officers could void a ticket.

Chief Khatib, who has been on the Lawrence police force for over 20 years, said in a 2014 deposition that fixing tickets as favors was done by the department before 2005.

“I would agree to prior to the 2005 policy change, yes, officers had fixed tickets for friends and family,” Khatib said in a 2014 deposition. “And I think I’ve said that that environment then was more relaxed.”

The city created a policy in 2005, but it is not clear how much changed after the policy was put in place. The Journal-World sought copies of dismissal forms from 2005 to 2012, but the city was unable to produce those forms. See our related article on that matter.

A review of documents related to former officer Monroe’s wrongful termination lawsuit — which was dismissed in August 2015 — tells of officers voiding tickets for friends, family members, KU employees and others even after the 2005 policy was put in place.

Former Lawrence Police Chief Ron Olin

The 2005 policy seemed to come about based on concerns that some city employees who weren’t in law enforcement were voiding tickets. The 2005 policy stipulated that only the issuing police officer or a prosecuting attorney had the power to void a ticket, former Police Chief Ron Olin told the Journal-World. Around that time, a city employee “who was not one of the two originating sources” voided a ticket, he said.

Citing the issue as a personnel matter, Olin would not say who the employee was.

Around the same time, former City Manager Mike Wildgen said he was encouraging city employees to void some parking tickets issued by police on KU football game days to help improve relationships with out-of-town visitors.

“Some of the people, they were coming from out of town and getting $60, $80, $100 tickets for parking there,” he said. “On real big game days people were parking right up to the corners. But people would write nasty letters to us, ‘we’re never coming back to Lawrence and you are mean to us.’ And that type of thing. I don’t doubt that I probably encouraged some tickets to be voided.”

The 2005 policy was replaced in 2012 as the department was weathering a ticket scandal alongside KU. One sergeant — who ultimately lost his job — was accused of voiding six traffic tickets for a KU employee. That August the department implemented a new policy requiring officers to fill out void forms and requiring those forms to be maintained by the city for at least seven years.

Other instances

Of the 927 requests submitted, Stoddard — who served as the Journal-World’s primary city contact, in part because much of the reporting for this article was done prior to the arrival of City Manager Tom Markus — said the city found that only in one instance “may there be introspection needed.” That one instance was the ticket voided for a local dispatcher, which was ultimately approved by Chief Khatib.

But Stoddard said this one instance was not enough to determine that there was a systemic problem with how tickets are voided.

Upon further analysis, the Journal-World found several other requests that are noteworthy. They include:

• Former City Commissioner David Schauner was cited for speeding in January 2013.

David Schauner

On the form explaining his reasons for voiding the ticket, the issuing officer said “during the traffic stop, the court copy was given to the driver by mistake. I became aware of my mistake and found the driver several hours later. In the interest of good public service, I told the driver I would request to void his citation.”

Schauner said in an interview that he recalls the incident well. He said he was “stunned” when the officer arrived at his home later in the day.

“He shows up at my door about 30 minutes later and said ‘do you still have that ticket?'” said Schauner, who was not on the commission at the time.

Schauner said he told the officer he did have the ticket and that he had never before received a ticket in Lawrence.

“He said ‘well you still don’t have one,'” Schauner said.

Schauner said he doesn’t believe favoritism played a part in the officer’s decision to void a ticket, but he could not explain the officer’s motivations.

“I didn’t ask for one (an explanation) and he didn’t offer one,” he said. “I’m not looking this gift horse in the mouth.”

• One police captain voided one ticket for operating under the influence and speeding. The request’s approval is signed by a sergeant rather than the captain’s supervisor.

When asked whether the city’s policy allows for proper checks and balances and whether a subordinate officer would be reluctant to deny a request from a higher-ranking officer, Stoddard said the instance does fall within city policy.

“All forms must be approved by a supervisor — not ‘the’ supervisor — of the requesting party. One of the reasons our police sergeants and captains were promoted to a position of supervisor authority was because the Chief of Police believed they possessed superior judgement, independent thinking, and a desire to follow protocol to the letter,” she said in a statement. “These qualities help guard against reluctance to deny a request.”

The charges related to the dismissed ticket ultimately were refiled with a new ticket.

• One officer in January 2013 requested to void a citation for a vehicle parked with an expired tag.

The officer’s rationale on the request form was vague and the only reason he offered for the request was “citation not issued.”

• Another captain requested to void a parking ticket issued to a Secret Service agent who was surveying a particular site in Lawrence for an upcoming visit from the president of Colombia. The captain asked to void the ticket because the agent was “on official business.” Chief Khatib approved the request.

• An officer this January requested to void a ticket he issued for running a red light.

“Forgot to issue citation, unable to locate subject,” the officer wrote. The request was approved.

When asked about the Journal-World’s findings, Stoddard said, “Patterns and practices at any police department change and improve over time. What was culturally acceptable at one time may not be later acceptable. Prior to 2005, the practice of voiding or dismissing tickets may have been more common for some officers.

“However, it was never acceptable to do so with any frequency or to do so for those that an officer had received anything from in return.”