KU professor: Fixation on ’60s prevails, but today’s racial injustices require new backdrop to understand

The civil rights movement of the 1960s was rife with heroes, villains and drama.

Racism was outright. Blacks were explicitly excluded — often in writing — from facets of society. Those problems were clear and tangible.

It’s no wonder the era has made for compelling books and movies, such as the recently released award-winning film, “Selma.”

It’s also no wonder that the events of the ’60s — which are marking 50-year anniversaries this decade — weigh heavily in civil rights conversations of today. But in a new book, Kansas University associate professor of African and African-American History Clarence Lang argues they weigh too heavily.

Clarence Lang

50 years after the Strong Hall Sit-In

An upcoming event on the Kansas University campus will commemorate a significant civil rights event on the Lawrence campus, the Strong Hall Sit-In of 1965.

The event, which is free and open to the public, is planned for 5:30 p.m. Monday in the Forum at Marvin Hall, 1465 Jayhawk Blvd.

The event will include a panel discussion featuring a number of former KU students who participated in the original sit-in, when hundreds of students — black and white — marched into Strong Hall to peacefully protest racial discrimination and the policies that supported it at KU.

More than 100 students who refused to leave the building at closing time were arrested, and additional protests and conversations ensued that ultimately led to change at KU.

“We have gotten to the point where the ’60s have done more than inform how we think about political, cultural and social challenges today,” Lang said. “It can actually undercut our political imagination and analysis.”

Lang argues in his book, “Black America in the Shadow of the Sixties: Notes on the Civil Rights Movement, Neoliberalism, and Politics,” that today’s civil rights threats take a different form, and as such, today’s civil rights injustices must be weighed against the new backdrop instead of the old.

Lang said his book stemmed from a 2012 blog post about the death of Trayvon Martin, the black teen shot and killed that year by neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman in Sanford, Fla. At the time, Lang said, he was struck by how many people were framing Martin’s death within the narrative of the 1960s.

“People were talking about it as if the circumstances around this death reflected a kind of racism that we had passed,” Lang said. By doing so, “we’re actually misunderstanding the context.”

Between then and the book publication, Lang’s thesis was bolstered by ensuing events, including the acquittal of Zimmerman and, more recently, police shootings in Ferguson, Mo., and other communities.

Unlike the outright racism of 50 years ago, Lang said the new racism — and new context in which such events must be viewed — is a set of social and economic policies that negatively affect black Americans, as well as Americans of all races who are poor.

On their face such policies are neutral, but their effects are inequality, he said. Examples range from mass incarceration to lack of living wages, he said.

Lang said those differences also call for a different kind of activism.

“The issues are not the same as they were in the 1960s; therefore, neither can the response be the same,” he said. “I think all of us engaged in ideas of social justice need to think about how that looks in light of conditions we actually face and not based on a narrative we have dragged with us for 40 years.”

Two local leaders who were involved with the civil rights movement of the 1960s reflected on differences between then and now.

Bill Tuttle, KU professor emeritus of American History, arrived in Lawrence in 1967 and taught KU’s first black history course in 1968, he said. Tuttle said the narrative for his coming of age was the civil rights movement of the ’60s, and while the decade’s message of equal rights is still relevant for some situations today, it can’t explain all.

Now, Tuttle said “entrenched economic issues” and “de facto” racism and segregation lead to a form of racism that’s less cut-and-dried than the legal segregation blacks fought against in the 1960s.

“There’s a multitude of those, and they’re all disturbing,” Tuttle said.

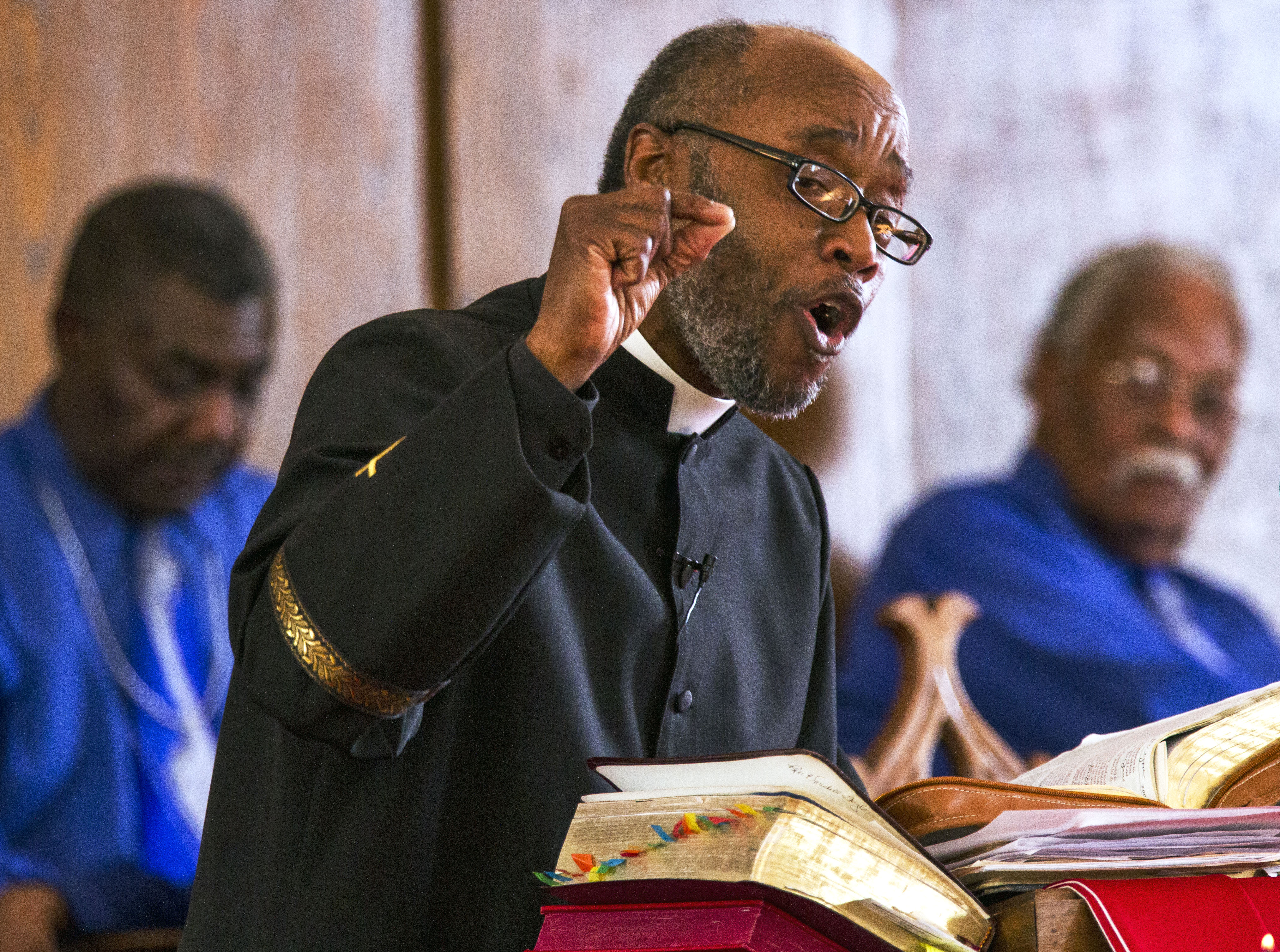

The Rev. Verdell Taylor Jr. delivers a sermon during a worship service at St. Luke AME church, 900 New York St., on Sunday, Feb. 16, 2014.

Verdell Taylor Jr., pastor of St. Luke AME Church, said it’s important for older and younger generations to keep talking.

“We felt the pain. We felt the dog bites and the fire hoses and things like that,” Taylor said. “Our younger people today have not lived that — not that they need to.”

Taylor said dialogue can help today’s young people understand the significance of the past and update momentum achieved by older generations to stay relevant.

“Nobody wants to get stuck in the ’60s,” Taylor said.

“That’s something that will be forever there. But to make it, you have to go beyond that.”