Renaissance man

Exhibit honors native son whose artwork became the bold signature of a new era in black culture

Study for Aspects

Susan Earle, curator of European and American art at the Spencer Museum, organized Aaron

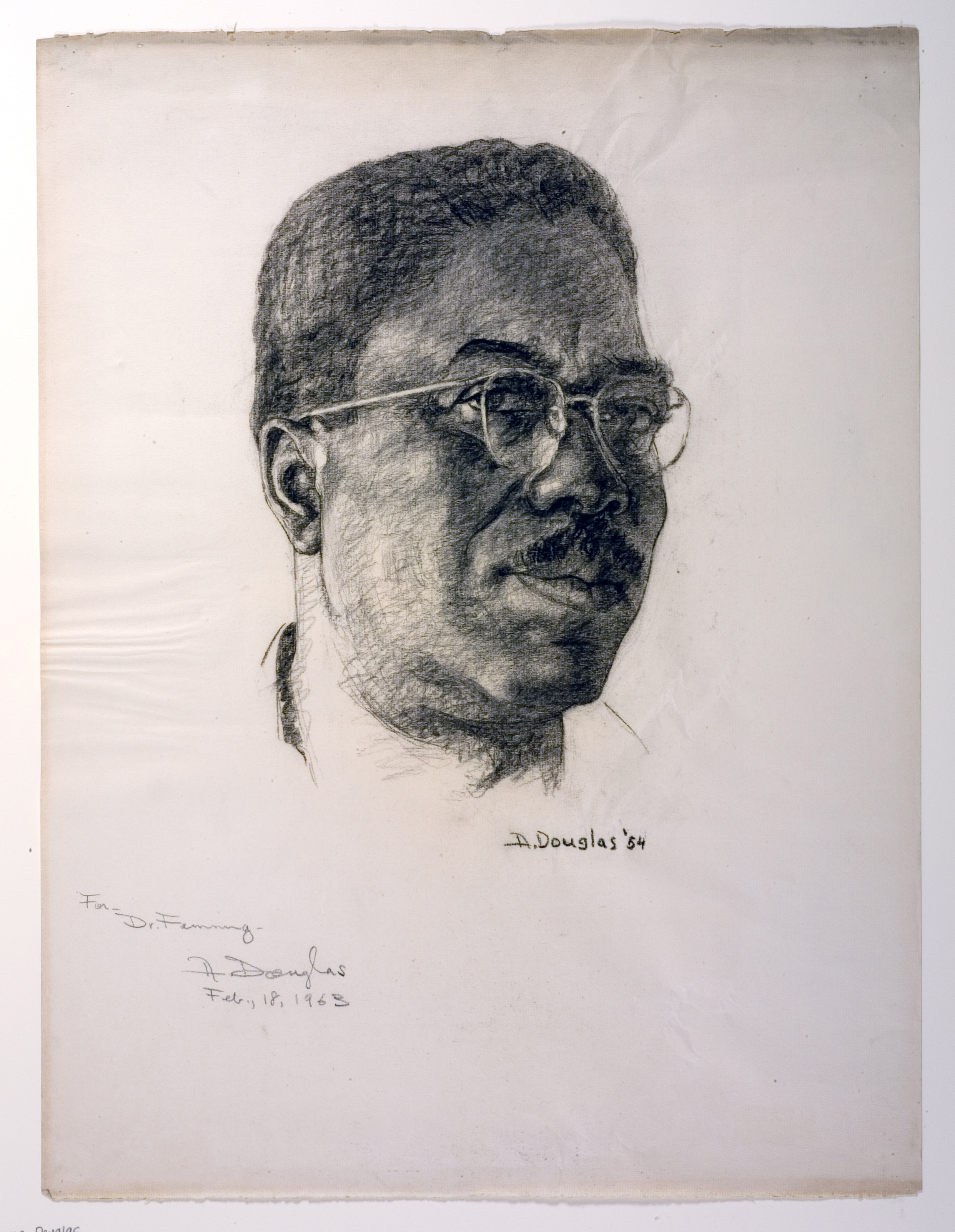

Aaron Douglas self-portrait (1954).

Growing up in Topeka, Cyrene Holt knew that her uncle – “the artist” – was making important work in New York.

“Everyone was really impressed with what he was doing,” Holt says. “But thinking that he was going to be famous or known – I don’t know if that was thought of because of the fact that black people weren’t recognized in that way.”

That’s hard to imagine today, given the place in history that Holt’s uncle carved out for himself.

Aaron Douglas was his name, by the way.

Now he’s considered the foremost artist of the Harlem Renaissance – a pioneer who boldly blended the modernist aesthetic of his day with narratives that celebrated black history and culture in a manner that could only be perceived as political in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s.

The Spencer Museum of Art celebrates the groundbreaking work of the Topeka-born artist this fall with the first nationally touring retrospective of his work. It’s the largest Douglas exhibition to date, with nearly 100 paintings, portable murals and illustrations, gathered from public and private collections across the country.

It’s accompanied by a 272-page book, edited by exhibition curator Susan Earle and brimming with color illustrations. Essays contributed by leading scholars argue for Douglas’ rightful place as a major figure in 20th-century art.

The scale of the exhibition – not to mention the care taken in eight years of planning the show and related programming – seems to reinforce that argument.

“It had its own momentum, outside of any of our vision,” says Saralyn Reece Hardy, museum director. “I think that just grew from the artistic depth of an artist like Douglas, who dared to take his paintbrush beyond the studio.”

Early bloomer

Cyrene Holt, now 67, wouldn’t fully appreciate her uncle’s prominence until she got older. In the 1940s, when she was still a child, Douglas was simply the mild-mannered, soft-spoken relative who visited from time to time.

She didn’t know then that Douglas always had been on a mission.

From his senior year, when he illustrated his second cover for the Topeka High yearbook – the volume in which his classmates deemed him “the best artist in school” – he let it be known that he aspired to make art for a living.

“When you look at those yearbook covers, you see that he has a very strong design sense,” says Stephanie Knappe, exhibition coordinator. “He was taking art classes at Topeka High, but there’s definitely an innate talent there.”

Douglas studied art the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, where he was exposed to progressive journals like The Crisis, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois. On those pages, he saw words and images about African-Americans, by African-Americans, Knappe says, and he began thinking he might have something to contribute to the cultural scene percolating in Harlem.

So after teaching art for a few years at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Mo., Douglas set off for the Big Apple.

“He arrives in New York in the summer of 1925, and it’s a matter of months before he’s asked to contribute illustrations to Alain Locke’s ‘The New Negro.’ He was the only African-American artist to be asked to contribute work to that publication,” Knappe says. “His work is appearing on covers and inside journals like Opportunity and Crisis. He’s collaborating with Langston Hughes.

“His work really becomes in high demand shortly after he gets to New York.”

‘Amazing person’

Kansas University Chancellor Robert Hemenway pitched the idea for a Douglas exhibition in 1999, the centennial of the artist’s birth.

“He felt that Douglas was a really important native son of Kansas and that this would be a logical place for us to initiate a project on this artist and to celebrate his life and work,” says Susan Earle, curator of European and American art at the Spencer.

She’s been working on the project since then, and has done her best to get to know Douglas – whom she never met – by looking at his art, reading his letters and talking to his friends and former students.

“He obviously was extraordinary,” Earle says. “I don’t think you could make the kind of art that he made without being an amazing person.”

People recognized that about Douglas during his lifetime. In 1930, historically black Fisk University commissioned him to paint a mural cycle for Cravath Memorial Library. Later, Douglas founded the school’s art department and churned out generations of students influenced by his style and convictions.

Four years later, he painted perhaps his best-known works – a four-part series of murals titled “Aspects of Negro Life” – at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). Commissioned by the Public Works of Art Project, the giant portable canvases are on view in the Spencer’s Central Court.

Murals that can’t travel because Douglas painted them directly on walls are represented in the exhibition with a short film created by KU theater and film professor Madison Davis Lacy and two recent KU graduates.

“To (shoot) these murals, we had to climb up on scaffolding that we had to cobble out of things that were available to us,” Lacy says. “You can’t believe the amount of light we had to pour into Cravath Hall just to get this imagery to pop out.”

‘Spirit of optimism’

Cheryl Ragar, a KU doctoral student working on a dissertation about Douglas, says the murals he created in the 1930s represent the pinnacle of his public achievement.

“He’s really telling a long history of black America,” she says in Lacy’s film. “And this is important because that really hadn’t been done visually before that.”

She notes that the distinctive silhouetted bodies in his paintings draw from Egyptian iconography.

“In the 1920s is when King Tut’s tomb had been discovered, and so there was a recognition that the people who had created these great civilizations in Egypt were not white-skinned people,” Ragar says.

It wasn’t just Douglas’ immediacy – his use of cubist and art-deco styles – that inspired the exhibition’s title, “Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist.”

“He was very much a modernist in the sense that he believed in progress, despite the toughness of the subject matter and the real-life situations and history that he was addressing,” Earle says. “He does paintings that directly address slavery, lynching, tough global issues.

“But he manages to convey them in a way that often also has a spirit of optimism.”

Recognition from home

Complementing the show, which opens Saturday, will be a national interdisciplinary conference called “Aaron Douglas and the Arts of the Harlem Renaissance.”

Book discussions, a jazz film series, gallery talks, a public mural commission and a performance by the Fisk Jubilee Singers are among the other activities scheduled in conjunction with the exhibition, which is sponsored in part by the World Company.

John Edgar Tidwell, a KU English professor who will lead one of the book discussions, says the collection of events – much like the Langston Hughes symposium in 2002 – marks an important moment for the university and the state.

“Kansas suffers nationally from a very poor image,” he says. “By exploring someone like Aaron Douglas, we get a richer sense of the state itself and what it has done in shaping African-American art and culture.”

It was here – in 1970, nine years before his death – that Douglas was treated to his first retrospective, at the Mulvane Art Museum in Topeka.

Cyrene Holt was there. In fact, it was the last time she saw her uncle.

She has been gratified by the recognition Douglas continues to receive, including a giant recreation of one of his “Aspects of Negro Life” murals on the side of a Topeka building.

She’s especially thrilled about the Spencer show, which will travel to Nashville, New York and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

“To see an exhibit of this magnitude,” she says, “is really impressive.”

The life of Aaron Douglas

May 26, 1899: Aaron Douglas is born in Topeka

Fall 1913Spring 1917: Attends Topeka High School

January 1918Spring 1922: Enrolls in the School of Fine Arts at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and earns his B.F.A.

Fall 1923Spring 1925: Teaches art at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Mo.

Summer 1924: Enrolls in the summer session at Kansas University

Summer 1925: Moves to Harlem in New York City; studies with German emigre artist Winold Reiss; begins contributing work to Opportunity, the magazine published by the National Urban League

Fall 1925: Takes a job in the mailroom of the NAACP’s journal The Crisis at the invitation of W.E.B. Du Bois; contributes illustrations to Alain Locke’s influential “The New Negro: An Interpretation”

1926: Creates covers for Opportunity and The Crisis; marries Alta Sawyer in June; co-founds the short-lived Fire!! A Quarterly Journal Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists

1927: Joins the staff of The Crisis as its art critic; illustrates James Weldon Johnson’s “God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse” and designs dust jackets for the work of such authors as Arthur Huff Fauset, Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen; paints a mural for Club Ebony in Harlem

1928: Receives a fellowship from the Barnes Foundation; serves as art editor for “Harlem: A Forum of Negro Life”

1929: Illustrates Paul Morand’s “Black Magic” and Andre Salmon’s “The Black Venus”; designs dust jackets for the work of Wallace Thurman and Claude McKay

1930: As an artist in residence at Fisk University in Nashville, paints a cycle of murals for the Cravath Memorial Library; creates the photomural “Birth o’ the Blues” for the College Inn Room of the Sherman Hotel in Chicago

19311932: Studies art at the Academie Scandinave in Paris; returns to New York in July 1932 and settles into the prosperous Sugar Hill neighborhood of Harlem

1933: First solo exhibition at Caz Delbo Gallery in New York in May; paints the mural “Evolution of Negro Dance” for the Harlem YMCA

1934: Participates in the annual traveling exhibition sponsored by the Harmon Foundation; commissioned by the PWAP (Public Works of Art Project) to paint a mural program entitled “Aspects of Negro Life” for the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library

1935: Becomes first president of the Harlem Artists Guild

1936: Participates in the first American Artists’ Congress; paints a four-mural cycle for the Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas; honored by a one-person exhibition at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

1937: Receives a Julius Rosenwald Foundation fellowship to travel to historically black colleges in the South

1938: Accepts a position as an assistant professor of art education at Fisk University in Nashville; receives a second Rosenwald fellowship to paint in Haiti, the Dominican Republic and the Virgin Islands

1941-44: Enrolls in Teachers College at Columbia College in New York where he earns an M.A. in 1944

19511952: Receives two Carnegie grants-in-aid through the Improvement of Teaching Project to paint on the East and West coasts

1955: Enrolls in a course on printmaking and enameling at the Brooklyn Museum Art School

1956: Travels to Europe and West Africa with wife Alta and friends Dr. W.W. and Grace Goens during the summer

Dec. 29, 1958: Alta dies unexpectedly at the Wilmington, Del., home of the Goenses

1963: Visits the White House as a guest of President John F. Kennedy for centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation

1965: Restores his mural cycle at Fisk University during the summer

1966: Retires from Fisk University

19691971: Initiates a second campaign to restore his murals at Fisk University; travels back to Topeka for a retrospective exhibition at the Mulvane Art Museum on the campus of Washburn University in the fall of 1970; is honored with a second retrospective in the spring of 1971 at Fisk University

1972: Fisk University designates a section of its new John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library the “Aaron Douglas Wing”

1973: Receives his honorary doctorate from Fisk in May

1974: Is featured in the filmstrip “Profiles of Black Achievement”

1975: Presents his papers to Fisk University’s Franklin Library

Feb. 2, 1979: Dies in Nashville