Rural population in decline

Future of small farms in doubt

Rural Kansas, once the backbone of the state economy, is going through a series of painful changes, expert panelists told a Kansas University audience Thursday.

“The state of rural communities is tough,” said Tom Gissel, who farms 7,000 acres with his brother near Larned. “We’re aging and we’re depopulating,” losing schools, post offices and other services that hold the communities together.

Gissel was one of six Kansas farmers who spoke Thursday afternoon at “Farmers, Food and Rural Communities in the 21st Century” at the Kansas Union. The forum came on the heels of a U.S. Census Bureau report showing that most of the state’s counties are losing population — and that 30 rural counties lost more than 5 percent of their residents during the first half of this decade.

Karl Brooks, a KU assistant history professor, said the forum was intended to spark thinking about how the state’s farmers could meet the future.

“Kansas has a lot going for it, and not all Kansans subscribe to the gloom-and-doom paradigm,” Brooks said.

But the tone of the presentation was far from optimistic.

“I live in a rural ghetto,” said Pete Farrell, a Greenwood County cattle rancher. “Do you know what a ghetto is? It’s where people are so poor they can’t leave.”

Panelists recited a litany of woes for traditional agriculture: it’s too reliant on distant markets, Americans have little understanding about the source of their food and corporations are muscling aside family farmers.

“I think the big corporations are protected more than they should be, supported more than they should be,” said Laura Fortmeyer, who farms and ranches near Fairview in Brown County.

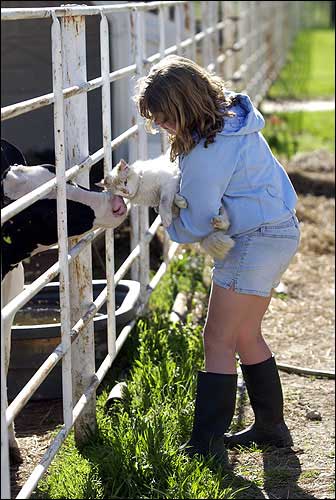

Brittnay George, 9, introduces her her farm cat, Whitey, to a calf Thursday during a break in feeding her bucket and bottle calves. The George family, including Brittnay, her brother Casey, 13, her mother, Laura, and father, Eugene, live south of Lawrence. Together, they run a dairy farm with 110 head of Holstein cattle.

Gissel said farmers also suffered because consumers had no idea how food ended up on their tables.

“I prefer to call them the eater,” he said. “I think there needs to be education for the eaters.”

Nancy Vogelsburg-Busch, a sheep farmer near Home City, agreed.

“Folks should know how their beef is made,” she said, “and who makes it.”

The event was sponsored by the Kansas Farmers Union. Emil Mushrush, the union’s secretary, said he hoped the faculty on hand would take Thursday’s testimony back to the classroom.

“It’s important they understand the farmers’ problems and educate their students in the community,” Mushrush said.

Despite the outlook, panelists said they remained committed to farm life.

“The worst job I have on a farm isn’t that bad,” Gissel said, “because I want to be there.”