POWs unchain memories

American prisoners reunite 6 decades later

Kansas City, Mo. ? Brought together again by their uncommon wartime bond, seven retired U.S. Navy sailors and Marines, all in their 80s, were in a hotel outside Kansas City, Mo.

They spent World War II, from start to finish, 1941 to 1945, in Japanese prisoner of war camps.

They were captured when the Japanese invaded Guam on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After three and a half years of beatings, starvation and otherwise gruesome conditions, they were liberated and sent back to the United States on Sept. 10, 1945.

Don Binns, 86, a former Lawrence mayor, city commissioner and Lawrence High School American government teacher, organized the annual reunion of the POWs. They’ve met at a hotel near Kansas City International Airport for the past 15 or 16 years. Nobody remembers exactly how long it’s been.

“Old minds,” somebody said.

A sword story

On a recent rainy Friday afternoon, Binns and some of his comrades were sitting in a tiny hotel room at the Lexington Suites Hotel.

They were telling stories that the intervening decades have made only slightly less painful or frightening.

“I was stripped of all my clothing, taken into a large room and put on my knees with my head down,” Binns said softly. “A Japanese captain pushed the edge of his sword down, against the back of my neck. He told me, in perfect English, that he would behead me if I didn’t tell where we’d hidden our weapons.”

Binns lied, saying there were no weapons.

He figured the UCLA graduate with the sword knew he was lying.

These U.S. military veterans met last week for a reunion in Kansas City, Mo. Now in their 80s, they were captured on Dec. 8, 1941, on Guam and spent the duration of World War II in Japanese prisons. All began their incarcerations at the Zentsuji Prison Camp. From left: Howard Ross, 86, Melbourne, Fla.; Harris Chuck, 86, Vista, Calif.; Donald Binns, 86, Lawrence; Richard Salsbury, 82, National City, Calif., and Robert Epperson, 84, Cottonwood, Calif.

There were no more questions, only silence and the weight of a sword at the base of his skull.

In the quiet room, Binns heard the sword slice through the air as it left his neck and heard it “swoosh” on its way down.

“For a minute I thought he’d actually cut my head off, ” Binns recalled, laughing loudly. “Hell, my life even flashed in front of me.”

The small room filled with laughter.

‘One ironclad rule’

That reminded former Marine Howard Ross, Melbourne, Fla., of his sword story.

“A Japanese general on a white horse threatened to cut my head off because I splashed some water … he even drew his sword,” Ross said frowning, waving his arms over his head.

Retired Marine Harris Chuck, Vista, Calif., interrupted.

“I don’t think they could find a blade sharp enough to cut through that thick skull,” he said, landing a soft right hand to Ross’ shoulder.

At 86, Chuck, an ex-drill instructor and retired sergeant major with 30 years in the corps, looked like he still could be a handful.

While the stories continued at one end of the room, Binns talked about the group.

“We were never this close in camp,” he said. “Life there was tense, tempers flared, and we fought a hell of a lot.” He smiled and waved his finger in the air. “But, we had one ironclad rule: You had to go outside to fight. You start swinging your arms in a small room with 28 people in it, and you’d soon have 28 pairs of arms going at each other.”

Slave labor

The camp Binns was describing was the Zentsuji Prison Camp on the southern tip of Japan. It was the first stop for all of the prisoners from Guam. Some, like Binns and Ross, stayed in Zentsuji for the war’s duration. Others were sent elsewhere.

Each of prisoner was used for slave labor. The harshest camps used prisoners to mine coal, haul iron ore and move steel. Americans in Zentsuji were used to load and unload rail cars using only their backs and arms to move bags of rice, salt and ores. The bags usually weighed in the 100- to 200-pound range.

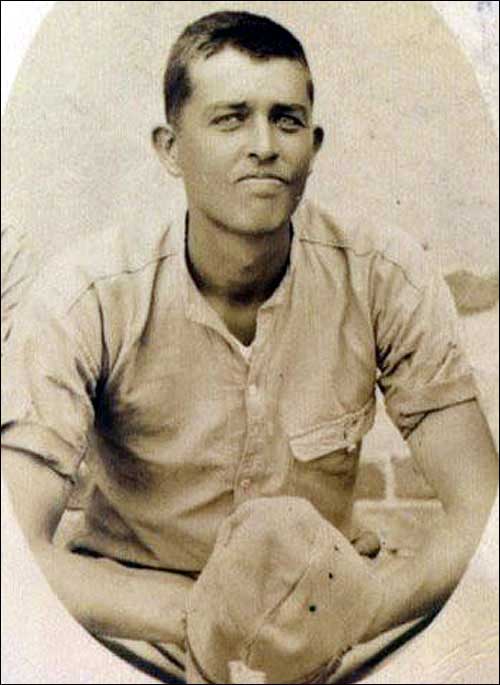

Binns

The prisoners were routinely tortured and beaten, usually at the whim of the guards. The captives’ daily rations consisted of two small bowls of watery soup and a portion of rice or barley, when it was made available. Their diets were supplemented by food they would steal at any opportunity. The penalty for stealing was a severe beating and a week in a tiny, dark cell with no water.

Many in the camps died or were killed.

The camp mortality rate at Zentsuji was 24 percent, lower than the average because prisoners had opportunities to steal food. More than 50 percent of the prisoners died in the coal-mining camp at Kyushu. By comparison, the mortality rate in German POW camps averaged about 2 percent.

“Having a loving wife or family to come home to increased chances of survival,” Binns said. “Many who lost hope did not survive … Others in worse physical shape fought with every ounce of strength and survived.

“Many a night,” he said, “I was awakened by the sickroom attendant to help carry a body to the ovens before reveille so morale wouldn’t sink any lower.”

‘Facing a firing squad’

Binns grew up tough on the outskirts of Kansas City. If he and his brothers and sisters couldn’t find someone to fight, they fought one another. He was 12 when he dropped out of school and hustled odd jobs to help sustain the family. In 1936, at age 17, he joined the Navy, furthering his education in the ports of Saigon, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Manila Bay.

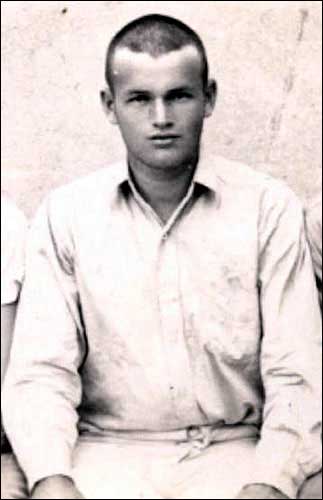

Epperson

His enlistment was up in 1940, and civilian jobs were hard to come by.

He re-enlisted and married his Kansas City sweetheart, Eunice Schmidt. Two weeks later Binns shipped out to Guam, and Eunice moved in with her parents. Fifteen months later Binns was captured by the Japanese.

After his encounter with the sword-wielding UCLA graduate, Binns joined 300 captives being held in a 16th-century Catholic church where they were kept for 30 days. Starvation rations made them weak. Tensions were high, and morale was low.

“Every time we heard the changing of the guard, we thought we’d be facing a firing squad.”

Physical scars

After a rough 1,500-mile ride crammed in the airless hold of a Japanese freighter and living on short rations of weevil-infested rice, the weakened captives arrived at the Zentsuji Prison Camp. It was a converted horse stable whose first occupants were captured New Zealand coast watchers.

Binns said the American officers in camp were given the option of working or staying in camp, living on half-rations.

“I was surprised how many chose to stay in their living quarters,” Binns said. “My opinion of most officers was never high afterwards.”

Ross

Shortly after daybreak, prisoners would be taken by truck to train stations within a 20-mile radius where they would spend the day loading and unloading cargo. Howard Ross pulled up his shirt to show brown scars running up the middle of his back.

“I don’t know if that’s from wearing a dead man’s shirt they gave me with a bullet hole in the back or if it was caused from chemicals leaking out of the bags we carried on our backs,” he said. “Anyway, I’m stuck with it.”

Smuggling food

At sundown the prisoners were searched before returning to camp. They soon discovered the only place that wasn’t searched was their crotch. They fashioned jock strap-like bags to wear around their waists where they would hide cans of fish or handfuls of beans, rice or sugar. The grains and sugar were extracted by poking a hollow piece of bamboo through the bag.

“When you’re starving you don’t care where your food has been,” Binns said, laughing.

There was no heat in the barracks. Rats and bedbugs were near epidemic. Prisoners got one hot bath every two weeks. All of the prisoners shared the same vat of water. Many opted for a cold sponge bath.

Card games and chess were taken seriously.

Sex ceased to be important, and most conversations involved food.

Medical students from the University of Tokyo visited the camp to conduct experiments.

Salsbury

“A group of prisoners were marched into a small room and guards with fixed bayonets formed a circle around us,” Binns recalled. “We were forced to let them insert a hypodermic needle into the center of our nipple, down through the nipple stem.”

They were told it was for dysentery.

When a student was injecting Ross, the needle broke into four sections in his breast.

Ross remembers the students laughing as he screamed in pain. Years later, doctors removed his breast.

Glimmer of hope

April 18, 1942, Zentsuji prisoners watched and waved when Col. James Doolittle’s bombers flew overhead, heading for Tokyo.

But after a few days, hope for liberation faded, and it was two years later before they saw another American plane.

When Binns was captured, his wife received a telegram saying he was missing in action.

In 1943, a ham radio operator picked up a message listing American captives in Zentsuji. He sent a telegram to Eunice Binns in Kansas City saying her husband was alive. Two years after arriving in Japan, Binns got his first letter along with a picture from his wife.

“That letter did more for my morale than anything that I might have imagined,” he said.

Chuck

As the war dragged on, religion joined food as a hot camp topic.

“Bibles, about six of them, were the hottest property in the camp,” Binns said.

July 4, 1945, American incendiary bombs destroyed 90 percent of Takamatsu, located just outside Zentsuji.

Months later Binns and surviving friends were back in the United States.

Lawrence teacher, mayor

Binns, like all the others meeting outside Kansas City, re-enlisted, and each spent at least 20 years in the military.

Binns and his family were in San Diego when he was released from the Navy.

“The old sailors say, ‘just throw the anchor over your shoulder and head inland as far as you can go and drop anchor,'” Binns said.

He dropped his in Lawrence and at age 39 enrolled at Kansas University. He graduated in three years and taught American government at Lawrence High School for 15 years.

His last eight years in the Lawrence school system were spent running the alternative high school.

He served two terms on the City Commission from 1975 to 1983 and spent time as the city’s mayor.

“There are three things I’m most proud of,” Binns said. “Starting the alternative high school, working hard as a commissioner to give the old police station at Eighth and Vermont to the senior citizens and pushing hard to get the Clinton Parkway approved.”

Will this group of Zentsuji survivors meet again next year?

“Hard to say. We used to have nearly 20 show up for these, and this year I think we’ll have seven,” Binns said. “We’re dying off real fast.”

| Don Binns, with help from his daughter, JoAnn Eunice Binns Sherar, wrote an ebook, “A Survivor’s Story,” detailing his life before and during the 3 1/2 years he spent in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. The former Lawrence mayor’s book sells for $9.95 and is available only online at www.ww2-stories.com.World War II veterans and their family members are encouraged to visit the site to share stories about war experiences, visit the photo gallery and visit the chat room. |

Photo gallery

Photo gallery