Mother: Foster care killed son

State to investigate death of 19-month-old in Lawrence

The attorney for the distraught mother of a 19-month-old boy who died five days after he was taken into state custody said the child would still be alive had he been left with his mother.

“This is a case where the system went too far,” said Scott Wasserman, a Lenexa lawyer. “Dominic Matz should not have been in foster care. He was fine when he was in his mother’s care. He died because he was in foster care.”

State officials said Tuesday they were investigating the death Sunday of Dominic James Matz, who died only days after being placed in a Lawrence foster home.

“We’re looking into the circumstances surrounding this (death),” said Sandra Hazlett, director of children and family services at the Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services.

“This is unfortunate, and we express our condolences to the family,” Hazlett said. “Other than that, I can’t say anything. Our hands are tied by confidentiality requirements.”

Asked if she suspected wrongdoing by either a social worker or a foster parent, Hazlett replied: “No.”

But Wasserman, who is representing Dominic’s mother, Tanya Jones of Paola, disagreed.

“She’s at the wake right now. She’s upset. She’s standing by the casket,” Wasserman said, speaking on a cell phone from outside the Wilson & Son Funeral Home in Paola. “I asked if she wanted to say anything, and her comment was, ‘No one should ever have to go through this again.'”

The boy’s funeral is today.

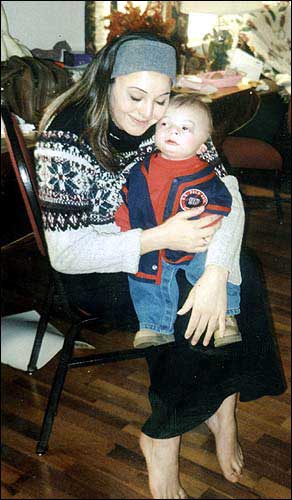

Tanya Jones and her son, Dominic James Matz, who died Sunday in foster care.

Records attribute Dominic’s death to “lungs filled with fluid,” Wasserman said, a condition his mother had been trained to prevent.

“It’s our contention that had the person who was caring for Dominic been properly trained, this wouldn’t have happened,” Wasserman said. “His mother did, in fact, have that training and was taking care of her son when he was taken away from her.”

Birth defects

Wasserman said Dominic had been diagnosed with CHARGE Syndrome, a condition tied to a set of birth defects known to delay physical and intellectual development.

The boy was admitted Jan. 7 to Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., after his mother became concerned he was having trouble breathing. At the time, Dominic weighed 13 pounds, 10 ounces.

“That’s not usual for a CHARGE Syndrome baby,” Wasserman said. “Lack of weight gain is one of the symptoms.”

Wasserman said Dominic was removed from his mother’s care on the eve of his Feb. 10 discharge from the hospital. He died five days later.

“This was not a case of abuse or neglect, it was a failure-to-thrive case — a case in which mom was accused of not taking care of him,” Wasserman said. “And we’re saying that’s not the case, that low weight is a symptom of CHARGE Syndrome babies and that Dominic was being taken care of.

“CHARGE Syndrome babies can survive and grow up to be happy and healthy,” Wasserman said. “Until Dominic went into foster care, he was a happy, loving child.”

After deliberations began whether to put the boy in foster care, Wasserman said, Jones was not allowed to see her son.

“She never got to say goodbye,” he said. “She never got to see him alive again.”

The boy was put in a Lawrence foster home supervised by The Farm, one of the state’s five foster-care contractors.

State to investigate

Under state law, SRS is not allowed to oversee investigations of deaths of children in its care. Instead, those investigations are handled by the state’s Child Death Review Board, a division within the Kansas Attorney General’s Office.

Results of these investigations are considered confidential unless the office decides to file criminal charges.

“We’ll be conducting an investigation of our own,” Wasserman said. “Our next course of action will depend on what we learn.”

It’s not known when the Child Death Review Board will complete its investigation.

Opening records

Lawmakers last year introduced legislation aimed at opening records of children who die while in state custody to public review. That followed the death of Brian Edgar, a 9-year-old boy who suffocated after his adoptive parents bound him head to toe with duct tape and stuffed a sock in his mouth.

The legislation stalled after key legislators disagreed on whether foster-care and adoption cases would be treated alike.

Edgar had been in foster care before he was adopted.

“I can’t say how far it’ll get, but we’re looking at a bill now that’ll let the Child Death Review Board still do the investigations but in a way that would be more open to the public,” said Rep. Brenda Landwehr, R-Wichita.

Landwehr is chairwoman of the subcommittee that oversees the SRS budget in the House.

| Dominic James Matz died of CHARGE Syndrome, a set of birth defects. “CHARGE” comes from the first letter in some common features.C = Coloboma and cranial nerves: A coloboma is a cleft or failure to close the eyeball that can result in vision loss. Cranial nerves take the form of facial palsy and swallowing problems.H = Heart: About 80 percent of children with CHARGE Syndrome are born with a heart defect, some of which can be life-threatening.A = Atresia of the choanae, which are the passages from the back of the nose to the throat, which make it possible to breathe through the nose: These passages may be blocked or narrowed but can often be corrected with surgery.R = Retardation of growth and development: Most children with the syndrome will be developmentally delayed, and some will be mentally retarded.G = Genital and urinary abnormalities: Many boys with CHARGE Syndrome have a small penis and/or undescended testes. Girls may have small labia. Boys or girls with CHARGE Syndrome may require hormone therapy to achieve puberty. Boys and girls may have kidney or urinary tract abnormalities, especially reflux.E = Ear abnormalities and hearing loss: Most children have unusual external ears, which may also be soft due to floppy cartilage.Other: Children with CHARGE Syndrome may have other birth defects, including cleft lip and palate or poor immune response. Many have weak upper body strength.Source: www.chargesyndrome.org |