Architecture makes powerful statement

Building's grand designs and subtle symbolism reflect distinguished political career

Steve Abend had a tough order when he was hired to design the Dole Institute of Politics building at Kansas University.

“There were lots of functional criteria — the parts of the building — that were relatively easy to accomplish through design and engineering,” said Abend, president of ASAI Architecture in Kansas City, Mo. “The parts that were more difficult were the intangible qualities. We had to understand what it would take to make a building represent a man, and that’s not often done.”

What KU officials ended up with was an $11 million, 28,000-square-foot building full of symbolism that represents former Sen. Bob Dole’s Kansas roots as well as his Washington, D.C., career.

“I think it’s the most unique building on campus,” said Warren Corman, university architect, “and probably the most unique in Kansas or the Midwest.”

Some of the symbols are obvious — like the 40-foot-high stained-glass American flag at the institute’s entrance. It was paid for with a $200,000 gift by Forrest and Sally Hoglund, KU alumni from Dallas.

Each piece of the 1-ton flag was American-made, said Steven Stepaniak, owner of Stained Glass Overlay in Roseville, Minn. It’s thought to be the largest stained-glass flag in the world.

“With everything we’ve experienced the last two years, this is such a great symbol of our country,” he said. “You can’t help but feel some sense of dedication to the United States. It’s very awe-inspiring.”

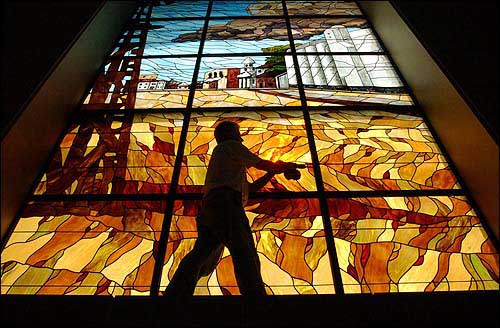

Nearby is a similar window, 22 feet high, depicting Russell, Dole’s hometown. Dole purchased the window to honor his parents.

On the floor between the two windows is an 11-by-19-foot red granite map of the state of Kansas, with Russell, Topeka and Lawrence as bronze insets, signifying important locations in Dole’s Kansas life.

Al Palmer of Stained Glass Overlay of Roseville, Minn., puts the final touches on a stained-glass window depicting Russell, the hometown of former U.S. Sen. Bob Dole, at the Dole Institute of Politics.

Above that is the Memory Wall, with photos of 960 World War II veterans. Dole suggested the wall to honor his late brother, Kenny, and other Kansas veterans.

Hidden symbolism

Some of the other signs might be lost to the casual observer.

Abend notes that the building’s limestone — which was quarried in Kansas — starts rough at the north end of the building and gradually is refined moving toward the south and the institute’s entrance, with its columns and reflecting pool, nicknamed “Polly’s Pond,” after benefactor and Dole friend Polly Bales.

“That reflects that idea of change, from (Dole’s) rural beginnings to the front, which looks a lot like buildings in Washington,” Abend said.

Abend said the circular shapes on the roof alluded to silos found at grain elevators. Inside, the unfinished roof area is reminiscent of that of a barn.

And Richard Norton Smith, the institute’s director, points out something else symbolic about the building’s design.

“You’ll notice there are no straight lines in the entire building — a great metaphor for the political process,” he said.

‘Unconventional’

In many ways, Smith said, the building is a reflection of the purposes it will serve.

In the center is the 3,300-square-foot Hansen Forum, named for the contributing Dane Hansen Foundation in Logan. It houses the institute’s exhibits, but can double as a theater for 250 people or 120 for a dinner.

The Simons Media Center, also on the first floor, is a 120-seat seminar room and broadcast facility that has Lawrence’s first satellite uplink equipment. Staff offices and a reading room for scholars also are on the first floor.

The basement is a 12,000-square-foot warehouse space, strictly climate-controlled, to house papers from Dole and other political leaders.

Smith altered the building plan when he arrived in 2001 to include the auditorium space and satellite uplink. He also eliminated a second room for scholars.

“It’s unconventional,” Smith said of the building. “It’s much more than an academic building. It’s as much a place where political scientists will do scholarly research as a place where people will debate political issues. It’s as much contemporary as commemorative. It’s important the institute be as much a place where fifth-graders come and are inspired in some way to render service as it is a place where a Pulitzer Prize-winning author will extract whatever riches the archive may contain.”

‘Impressive building’

The building’s initial cost was about $11 million, but Abend said KU officials “stripped it down” to about $6 million to present it to state leaders for funding and for private fund raising.

When Smith came on board in December 2001, he added more amenities to the building to bring the cost back to nearly $11 million.

The building was paid for with $3 million in state funds and $8 million in private and federal funds. The largest contributions came from Philip Anschutz, a KU alumnus and benefactor, and the Starr Foundation in New York City.

Abend said he was looking forward to this weekend’s dedication after working on the project since 1998.

“I think by its purpose and programming, it’s going to be an impressive building regardless of its architecture,” he said. “I’m pleased, judging by people’s reaction, the architecture is going to help with the prominence.”