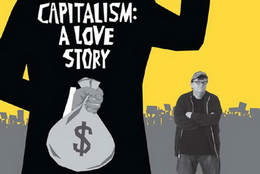

“Capitalism: A Love Story” angers and inspires

The timing is right. The entire world is struggling to find its way out of a recession. Middle America is pissed off and broke. U.S. unemployment is soaring and the economic meltdown continues. So along comes the provocateur filmmaker who has spent the last 20 years raging against the machine, and he’s aiming at a big, big target–the very economic system that his country is based on.

Michael Moore’s new documentary “Capitalism: A Love Story” may be a bit scattershot and it may employ many familiar tricks, but it’s nothing if not a challenging and personal movie from one of the most polarizing figures in politics today.

He calls himself a populist, but sometimes you have to wonder. Why–you may ask–didn’t Moore go for a smaller, less controversial prey? With President Obama being called a “socialist” at every turn and that word being villainized the way it is in the mainstream media right now, why didn’t he use his ample storytelling and heartstring-tugging skills to rally film audiences around a less contentious idea?

He calls himself a populist, but sometimes you have to wonder. Why–you may ask–didn’t Moore go for a smaller, less controversial prey? With President Obama being called a “socialist” at every turn and that word being villainized the way it is in the mainstream media right now, why didn’t he use his ample storytelling and heartstring-tugging skills to rally film audiences around a less contentious idea?

Well, if you think about it, Moore has always shot for the moon. “Bowling for Columbine” was not a documentary about gun control–it questioned the fascination our country has with guns and asks what that leads to. “Fahrenheit 9/11” didn’t only try to bring down a sitting President–it highlighted a culture of fear. “Sicko” didn’t just find flaws in the American health care system–it challenged viewers to re-examine what it means to be a citizen and have your country protect you.

Moore has always gone for the big picture; always tried to re-frame the argument. And to some extent, the buttons he pushes get people to talk. Many of the issues brought up in his movies have gradually seeped into the collective consciousness. Will the thesis of this movie do the same thing? Only time will tell.

His argument this time is simple. Capitalism is broken. Not only does it not work, but it’s immoral, anti-Democratic, and anti-American. From the start, he goes for the throat. He shows an old film of life in ancient Rome and while the dated voice-over talks about the fall of the Roman Empire, he cuts in images of modern America. There he goes alienating people again. His trademark sledgehammer style is certainly off-putting at times, but after watching the rest of the movie, it’s hard not to see the similarities.

His argument this time is simple. Capitalism is broken. Not only does it not work, but it’s immoral, anti-Democratic, and anti-American. From the start, he goes for the throat. He shows an old film of life in ancient Rome and while the dated voice-over talks about the fall of the Roman Empire, he cuts in images of modern America. There he goes alienating people again. His trademark sledgehammer style is certainly off-putting at times, but after watching the rest of the movie, it’s hard not to see the similarities.

The movie plays like a bookend to 1989’s “Roger and Me,” where he documented the decimation of his blue-collar hometown of Flint, Mich. after the closing of a GM plant. Things have only gotten worse since then. Moore is focusing his anger on the growing divide between the rich and the poor in America, as he again follows families that are being evicted from their homes.

He highlights “dead peasant” policies, an ugly life insurance practice that gives employers huge payouts when their workers die, while nothing goes to the family. He uncovers politicians who were given special refinancing deals by the same company that was capitalizing on sub-prime mortgage deals. He traces prominent banking executives who were appointed to Presidential cabinets and traces them back again to the private sector as they maneuver to increase their already obnoxious wealth at the expense of others.

This kind of rampant greed has stampeded out of control for quite some time, Moore says, and he traces its roots back to the Reagan administration’s heady de-regulation days. As big business got in bed with more politicians, the government opened the floodgates on the ways that corporations could make money exponentially and make sure that it was not against the law.

This kind of rampant greed has stampeded out of control for quite some time, Moore says, and he traces its roots back to the Reagan administration’s heady de-regulation days. As big business got in bed with more politicians, the government opened the floodgates on the ways that corporations could make money exponentially and make sure that it was not against the law.

This is a subject Moore is quite passionate about. By tracing his family’s roots back to an embattled worker’s strike in the 1930s and conversing with his father about the work ethic and pride that employees at the GM plant were instilled with back in the 70s, Moore really does spotlight how things have changed since then. He recalls a time when capitalism held the promise that everyone, if they worked hard enough, might someday share in some of the wealth. Juxtaposed with the cynical climate of today and the staggering statistic that the richest one percent of the country makes more than the other 99 percent combined, it’s easy to be nostalgic.

I like that Moore takes historical perspectives to remind everyone that what you think our country is now may not resemble what it was in the past. On a trip to Washington, D.C. this August, I again visited the Lincoln Memorial and it was striking to read the thoughtful, philosophical prose of a President who today seems a hundred times more liberal and progressive than I remembered.

So in the movie when a sickly Franklin Roosevelt appeared in a 1944 address to call for a “second bill of rights,” I was reminded of the courage it takes to stand up for “big picture” ideals that may not be popular at the time. When Jimmy Carter appeared with an altogether harsher tone in a TV address that condemned the greed and materialism that he saw in our society, I thought the same thing.

So in the movie when a sickly Franklin Roosevelt appeared in a 1944 address to call for a “second bill of rights,” I was reminded of the courage it takes to stand up for “big picture” ideals that may not be popular at the time. When Jimmy Carter appeared with an altogether harsher tone in a TV address that condemned the greed and materialism that he saw in our society, I thought the same thing.

I’m still not quite sure what Wallace Shawn (“The Princess Bride”) was doing in the picture as a talking head and I’ve seen enough of Moore’s stunts (such as putting yellow crime scene tape around banks and asking for the bailout money back) on the previews. On the other hand, so much of the information in the movie is so depressing that these moments were fairly welcome just for their lighthearted tone.

Connecting the dots between all this fascinating and frustrating material isn’t easy, and sometimes it seems like a 360-degree turn. Moore is on solid ground, however, towards the end of the film when he spotlights one factory in Chicago that fought back after told they were being fired and subsequently not paid for hours already worked. The single most inspiring moment in the movie comes during these events, and it’s good timing; it’s a call to arms.

Love or hate his tone and his methods, Moore is a gifted filmmaker who isn’t afraid to say exactly what he feels. He loves his country and–in his words–he’s not leaving. If he rubs you the wrong way sometimes, then we are in the same boat. But his idealism and refusal to back down to injustices he perceives are inspiring. But it’s not from him that I derive my greatest hope. For all the awful mistreatment of people in “Capitalism: A Love Story,” it’s hard not to be somewhat optimistic when you see what everyday people are capable of when they rally together.

Love or hate his tone and his methods, Moore is a gifted filmmaker who isn’t afraid to say exactly what he feels. He loves his country and–in his words–he’s not leaving. If he rubs you the wrong way sometimes, then we are in the same boat. But his idealism and refusal to back down to injustices he perceives are inspiring. But it’s not from him that I derive my greatest hope. For all the awful mistreatment of people in “Capitalism: A Love Story,” it’s hard not to be somewhat optimistic when you see what everyday people are capable of when they rally together.

Footnote: FDR’s 1944 speech called for the “right” to “adequate medical care,” “a useful and remunerative job,” “a decent home,” “a good education,” “adequate food and clothing and recreation,” and “the right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad.”

Footnote 2: There is no such thing as objective cinema. Every shot, angle, voice-over, piece of music has a point of view and is subjective. Every documentary you’ve ever seen has a bias.

Footnote 3: Propaganda is not inherently “bad.” It all depends on your perspective. Moore joins a talented propagandist club already populated by WWII-era geniuses like German documenatrian Leni Riefenstahl (“Triumph of the Will”) and beloved American filmmaker Frank Capra (“Why We Fight”).

“Capitalism…” is opening locally in Kansas City. Check fandango.com for showtimes.