Review: ‘The Great Tennessee Monkey Trial’

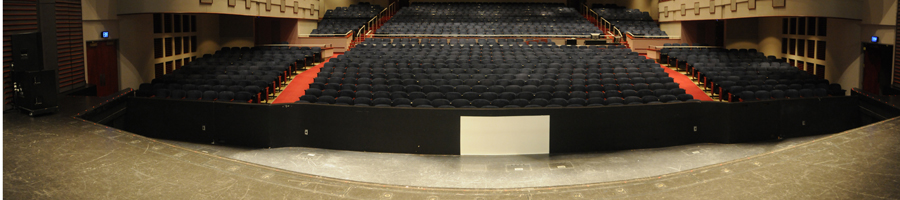

This review of “The Great Tennessee Monkey Trial,” which was presented Wednesday night at the Lied Center, is by Megan Helm, a Lawrence musician and educator.The battle between religion and science raged under the sweltering summer sun in Dayton, Tenn., in July 1925 as Clarence Darrow defended the right of science teacher John Scopes to teach evolution in a public school. Christian hero, politician and orator William Jennings Bryan joined the prosecution, and the scene was set for the Great Tennessee Monkey Trial. LA Theatre Works, a radio theater, presented an adaptation by Peter Goodchild based on the Scopes trial transcripts. The hybrid docudrama features costumed actors reading scripts with minimal blocking, a narrator and a foley artist for sound effects. The production came to the Lied Center Wednesday night.Spiritual music set the Southern scene as the actors assembled before a large dawn colored backdrop. This simple treatment allowed the audience to feel the heat as the lighting intensified and died throughout the days. Two large, old-fashioned tables frame the pulpit-like bench as the prosecution and the defense squared off in a duel between religion and science. In an ingenious plot hatched by local Dayton businessmen to attract commerce to their sleepy Southern town, science teacher John Thomas Scopes was asked to stand trial to challenge the constitutionality of Tennessee’s Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of evolution. The narrator, Shannon Cochran, looked like a modern attorney in her professional black dress. She remained off to the side and provided meaningful back story and connections. Journalist H.L. Mencken, played by James Gleason, appeared from time to time to reflect on the trial like a caustic Greek chorus. His accounts, taken directly from the articles he wrote at the time, paint the picture of a mass media circus and trial gone wild. After less than a week on the assignment, he packed up in exasperation and went back to New York. Ed Asner was brilliant in his interpretation of the prosecutor/preacher William Jennings Bryan. His monologues in the beginning of the trial were overconfident tributes to God and country full of holier-than-thou hellfire and brimstone. After his humiliating examination by Darrow, Bryan becomes confused and unsure of his literal understanding of the Bible. Completely living in the moment, Asner’s portrayal of the disoriented and breathless Bryan was so believable that one might have wondered if Asner, and not William Jennings Bryan, were really OK. John Heard easily assumed the role of Darrow. His humor and ironic wit played well throughout his banter with Bryan. In a situation where Southern traditions and faith took precedence over the law, Heard played Darrow’s exasperation to a tee. Dudley Field Malone, the divorce lawyer for the defense, played by Geoffrey Wade, offered coolness and compassion toward Bryan, and their mutual respect added an element of humanity and warmth to the drama. His compelling speech just before the intermission pleading with the people for quality education was regarded by Bryan as one of the finest he had ever heard. Judge John Raulston was endearingly played by Jerry Hardin, and Rob Nagle was the pious and self-indulgent attorney general, Stewart, who strived to maintain his image of the impeccably gentile Southern gentleman. Two Kansas University students were recruited to fill out the cast. Elizabeth Elliott strolled on as the adorable ex-girlfriend of John Scopes who sets him up for a paparazzi attack, and freshman Jeremy Ims took the stand as a 14-year-old science student. Looking like the innocent kid right out of an Andy Hardy movie, his testimony was full of adolescent charm.Courtroom dramas play well in the radio theater genre. The verbal sparring between prosecution and defense was more interesting than physical action as the actors rose, sat and paced. Heard occasionally didn’t make it to his microphone in time to catch a full line of dialogue, which was disappointing, but the delivery was full of conviction.The on-set foley artist sat back away from the action and provided the essential canned applause necessary to allow the audience to hear how the crowds reacted after each argument presented. Next month, the state of Texas will determine the viability of intelligent design in approved science textbooks. It’s a battle that has been raging since 1925 — both in real life, and on stage.