Ogallala water continues to pour onto farm fields despite decades of dire forecasts

Shutterstock image.

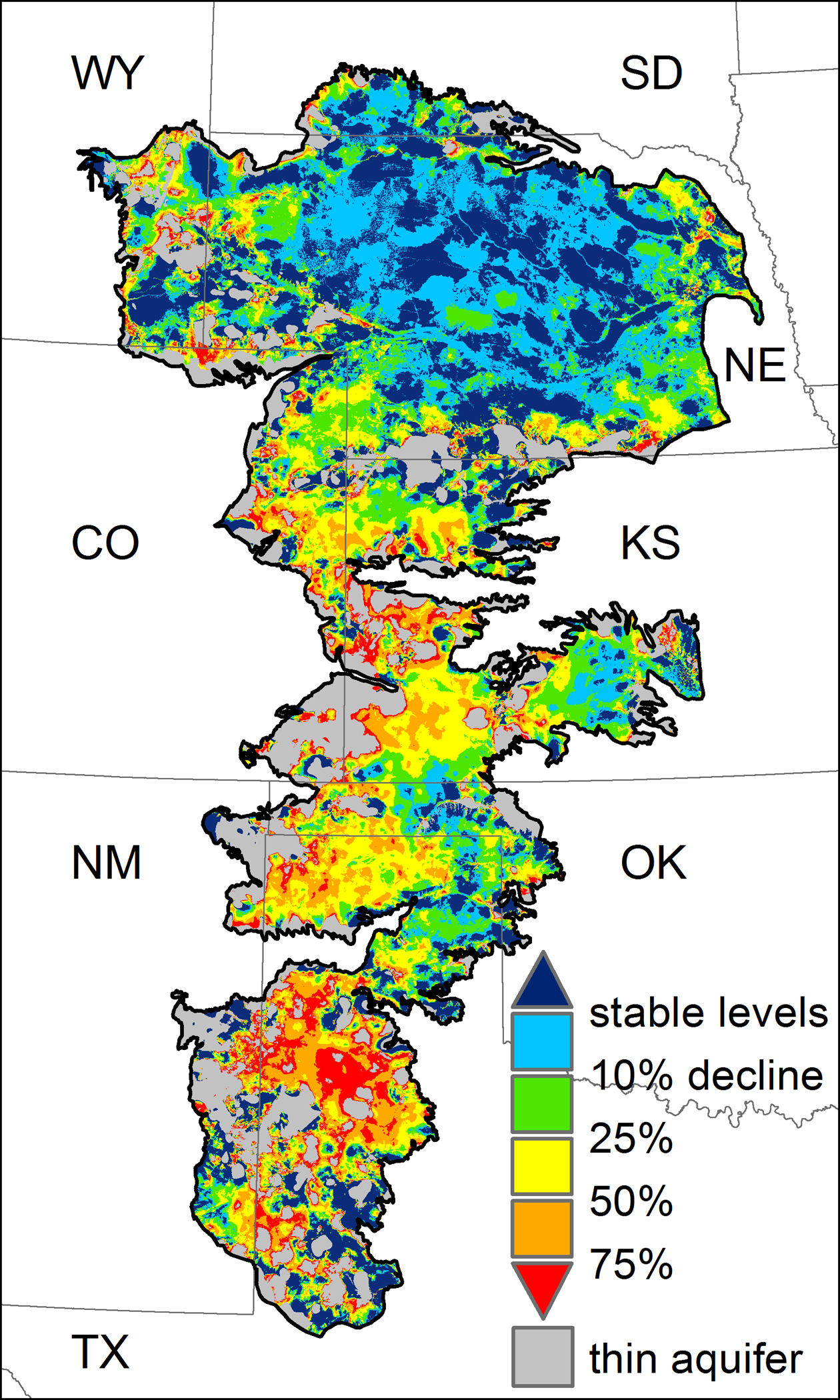

Significant portions of the Ogallala Aquifer, one of the largest bodies of water in the United States, are at risk of drying up if the aquifer continues to be drained at its current rate.

The five Groundwater Management Districts in Kansas are organized and governed by area landowners and large-scale water users to address water-resource issues. GMD's 1, 3, and 4 draw water from the High Plains Aquifer, a network of water-bearing rock formations hundreds of feet below the surface. GMD's 2 and 5 draw water from aquifer systems nearer the surface and which also provides municipal water to Wichita, Hutchinson and surrounding communities.

More than two years ago, Gov. Sam Brownback and the Kansas Legislature thought they had found a way to help save the ever diminishing and endangered Ogallala Aquifer, a massive underground water supply that has helped make Kansas one of the nation’s top agricultural states.

The Legislature, with Brownback’s strong support, allowed farmers to form groups that could require deep reductions in irrigation. The hope was that if enough Western Kansas farmers pared their water use by at least 20 percent, the aquifer’s lifespan could be extended.

Brownback, who grew up on a farm, explained that without Ogallala water, roughly two-thirds of the state’s agricultural and related businesses could be harmed.

“It is essential that we help protect, extend and conserve the life of the Ogallala Aquifer for future generations of Kansans,” he said at the time.

But two years later, only one group of 110 farmers, who own 99 square miles in Sheridan and Thomas counties near Colby, has formed.

“We had expectations of it catching on like wildfire,” said Tracy Streeter, director of the Kansas Water Office. “In Topeka we would have liked to see more flurry over this. It’s going to be a slower process than we thought.”

Since 1945, the state has been sounding the alarm that irrigators have been depleting the Ogallala.

The aquifer, a shallow, underground sea under parts of eight states and spanning 174,000 square miles, is the main source of water in the western third of Kansas. Counties on top of the aquifer account for roughly two-thirds of the state’s agricultural economic value.

Without Ogallala water, significant portions of the region’s agriculture and its related businesses could not be sustained, manufacturing could not continue, recreational opportunities would diminish and towns could vanish, state officials say.

For years Kansas farmers and government officials have wrung their hands and watched water vanish from the massive aquifer.

Task forces and blue-ribbon committees in Topeka and in Western Kansas have spent thousands of hours putting together reports warning that the aquifer was drying up because of over-pumping to irrigate crops. Western Kansas farmers have turned out in droves at public hearings to discuss the looming crisis.

“We have done a great job of admiring the problem,” said Jay Garetson, a farmer in Haskell County who has sued American Warrior, an oil and gas company that owns land adjacent to his, for not conserving water.

The lawsuit has pitted Garetson against one of Kansas’ richest businessmen, Cecil O’Brate, of Garden City, who owns American Warrior, and many farmers in southwestern Kansas.

“All of this was foreseen in 1945,” Garetson said. “The alarm was sounded again in 1972, and we sounded the alarm in 2005. We are going to continue this until all the wells won’t pump anymore. It is sad and frustrating.”

Decades have passed as committees made recommendations, the Legislature passed laws that were not enforced, officials looked the other way while farmers winked and nodded –and Ogallala water poured onto the fields.

The honor system fails

Farmers were never going to cut their use of water without mandates because it could harm them economically in the short term, Garetson said.

“It is counter to human nature,” he said. “Voluntary will never work.”

While laws on the books could be used to force farmers to limit water, officials have been reluctant to take that path, they said, even though they know farmers have overused water.

“It is heavy-handed,” said Lane Letourneau, whose job as project manager for the Kansas Department of Agriculture is to allocate water from the aquifer and to protect private-property rights.

“It is difficult for the state to come in and mandate something,” he said. “This is a big, long process. If we don’t have 100 percent, we could end up in court.”

Indeed, in five years, no farmer has had his water rights revoked because of the Ogallala’s diminishing water levels, the Journal-World found through an open records request.

Today many wells have little water left in them, and the issue of water is a daily discussion as the prospect of lost revenue looms. The issue has pitted farmers who have plenty of water against farmers who do not, farmers who want to conserve against farmers who do not. Some farmers have had death threats over the need to conserve.

Kansas hasn’t been alone in its search to stop farmers from depleting the Ogallala. To its south, Oklahoma is struggling, and in Texas, entire towns are going dry.

But Nebraska to the north took a tougher stance. That state passed laws in the 1970s to limit irrigators’ water allocations and provided other programs such as rotating water permits. Enforcing those laws was extremely difficult and has taken years, but today, instead of water aquifer levels dropping by dozens of feet, the aquifer is being sustained in many places and is actually being recharged in some, Nebraska officials say.

“We are far ahead of everybody else because we have had this in place since the 1970s,” said Dean Edson, executive director of the Nebraska Association of Resources Districts. “We don’t have a one-size-fits-all; we have different situations. But because of our active management we have increased our groundwater levels.”

A crisis is near

In spite of its dropping water levels, the Ogallala Aquifer, discovered in the 1890s, is still the largest underground water source in the U.S. It can be described as an underground egg carton made of silt and sand, with each of the egg “pockets” varying by depth. The depth of pools of water under farms near each other can vary greatly from 30 to 500 feet.

In 1945, with new irrigation technology being developed, the state realized that the water was not infinite. The Legislature passed the Water Appropriations Act, which established “first in time, first in right.” The law required water users to obtain state permits to use water for irrigation and other business-related activities.

The priority system allowed farmers who were already using water to be grandfathered in. They were considered vested with “senior” water rights that could be passed from generation to generation. After 1945, new users were identified as having “junior” rights. Several lawsuits unsuccessfully challenged the constitutionality of the act.

In the 1960s, with the belief that the country’s breadbasket could feed the world, large-scale irrigation was developed with center-pivot irrigation systems that were much more efficient than flood irrigation methods. That allowed farmers to extract water at a much faster rate and to irrigate not just on flat land but on hills, resulting in a tremendous increase in agricultural production.

From 1964 to 1978, farmers also adjusted to being able to grow more water-intensive crops.

The aquifer was experiencing massive drops in water tables by the 1970s. In semi-arid western Kansas, rainfall averages about 16 to 20 inches annually — not enough to grow the vast quantities of crops that were being harvested.

But there was plenty of wasted water, farmers agree today. Some farmers depended on the water so much that they felt like an unexpected rain interfered with their irrigation schedule, Garetson said.

In the 1970s, Kansas and Nebraska governments took a hard look at the water issue through a series of committee meetings that resulted in new rules and laws.

“Kansas, indeed, has major water problems, and a crisis is on the horizon. The declining water supply of the western third of Kansas threatens the agricultural economy of the entire state.” wrote Lt. Gov. Shelby Smith to Gov. Robert Bennett in the 1978 Final Report of the Governor’s Task Force on Water Resources.

From the task force recommendations, the state Legislature passed laws to set up five groundwater management districts that are governed by local boards and exist today. Board members are elected by the community. The districts over the years have identified research and regulatory needs within their boundaries. However, enforcement of water laws was left to the state’s chief engineer.

By 1978, both the Kansas and Nebraska legislatures had created a way to force farmers to reduce water. In Kansas, the state’s chief engineer was given the power to set up an Intensive Groundwater Use Control Area. Statutes allowed the chief engineer to designate a control area when local conditions require it or when local stakeholders request it.

Certain criteria had to be met:

- groundwater levels are declining excessively;

- the rate of groundwater withdrawal exceeds the rate of groundwater recharge;

- unreasonable deterioration of groundwater quality has occurred or may occur;

- waste of water has occurred and could have been prevented.

Since 1978, the chief engineer has set up eight small control areas in western and central Kansas because reservoirs and recreation areas were threatened by declining groundwater and not so much because crops and the Kansas farm economy were endangered.

The chief engineer hit farmers hard in those areas and reduced water applications for crops from 24 inches per acre per year to 6 inches per acre per year over five years in some cases. New water rights or applications were closed in some areas.

But the chief engineer and other state officials have been reluctant to use the law for farmers who are draining the aquifer.

“We think it is a harsh method,” Streeter said. “We would like to see groups of irrigators come together and work out a solution.”

In Nebraska, enforcement started slowly, but today, farmers in the drier parts of the state are allotted anywhere from 6 to 12 inches per acre of groundwater each year for irrigation, averaged over five years.

The Nebraska Legislature created almost two dozen Natural Resource Districts that gave farmers local control but required them to come up with a plan to reduce use of the aquifer. They also started educational campaigns to illustrate to farmers that there are more efficient methods of using the water, said Jaspar Fanning, a farmer and manager of the Upper Republican NRD, who has a doctorate in agriculture economics.

Initially the amount of water the farmer could use was set at 20 inches per acre annually. When the water table continued to drop, it was ratcheted down to 16 inches per acre and then 13 inches. Some farmers today only have access to 6 inches per acre of groundwater a year.

“We used the carrot and stick approach early on,” Fanning said. “Farmers are resilient. It’s not like somebody jerks the plug and shuts out the lights. It is a process that everyone will adopt to the changes that we face.”

An impossible task

Garetson, whose family moved to Haskell County in 1902, may be the most unpopular man in Western Kansas.

He and his family had watched for years as the Ogallala water table fell, and there never seemed to be a solution in sight. Wells were running dry, their children were getting older, and they worried that farming would not be a viable option for them by the time they grew up.

Water overuse had become much like prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s, Garetson said.

“So much winking and nodding about over-drafting of the aquifer that after a time it becomes a racket,” Garetson said.

In 2005 Garetson and his family decided to ask the state to drop the hammer. They filed an impairment complaint against their neighbor for taking too much water and lowering the water levels in the Garetsons’ wells. Garetson’s hope was that it would force the state to enforce conservation through an intensive groundwater use control area, much like it had with recreation areas.

For two years it looked as though a control area would be established.

The state conducted a study, meetings were held and a plan was being drawn up, he said.

“Everybody believed (the state) was reaching for the whistle,” Garetson said.

Then the landowner, a divorced woman with children, approached Garetson and his brother and asked them to drop the complaint, saying she would not be able to feed her children with the state coming after her.

“It is hard not to be sympathetic for any person, let alone a mother with children,” he said.

Garetson and his brother pulled their complaint but asked the state to continue moving forward and enforce the law.

“There were one or two meetings afterward, and they quit having meetings,” he said. “Then the referee went back on lunch break.”

Everything was quiet until 2010, when Garetson’s second cousin bought the land.

The Garetsons had several conversations with him about the water situation, but he “hemmed and hawed and thumbed his nose at us,” Garetson said.

The Garetsons discussed filing another impairment complaint but because the state had known about the situation for years and had done nothing, they decided to file a lawsuit in district court.

After the Garetsons filed suit in 2012, their cousin worked out a deal to sell the land to O’Brate, owner of American Warrior, an oil and gas business company, Garetson said. Even as their cousin was presenting himself as the owner of the land to the district judge, he had already sold the land to O’Brate’s company, Garetson said.

In depositions, the Garetsons learned O’Brate had actually paid their cousin’s legal bills, Garetson said.

“You can’t make this up,” Garetson said. “This thing has become so bizarre.”

O’Brate declined to comment for this story. The Garetson’s cousin did not return phone calls requesting an interview.

In May, a judge issued a temporary injunction supporting the Garetsons. The injunction prevented the company from using the wells for irrigation while the case goes through court. O’Brate has filed an appeal to the injunction in the Kansas Appeals Court.

The Garetson case is known by many in southern Kansas. Many farmers’ passions have flared, concerned that a case of neighbor-on-neighbor could spread.

The ordeal has left Garetson with a bad taste. He said his family has been abused. They’ve been shunned by the community, told to “shut up” and have received death threats.

“What I find appalling, we have statutory authority, and we are refusing to look out for the general public,” he said. “If we don’t enforce these rules, this basketball game is going to turn into a gunfight.”

Cutting water use

In Sheridan and Thomas counties in about 2011, a group of farmers approached David Barfield, Kansas chief engineer.

The farmers had a plan and wanted to reduce water use from the Ogallala by 20 percent to begin saving water for children and grandchildren. They believed by doing that they could add 25 years to the life of the aquifer, said Letourneau with the Kansas agriculture department.

Not all irrigators were on board, so the farmers were asking the state for the hammer — they wanted to file an impairment complaint. But the chief engineer didn’t want to do that, Letourneau said.

If the state opened a case and found that the aquifer levels were declining excessively or the rate of groundwater withdrawal exceeded the rate of groundwater recharge (which it did), then the state likely would have to require a more stringent plan with harsher remedies, Letourneau said.

Meetings were held with the state’s attorney general, and finally it was decided to ask the state Legislature to amend the state’s water laws to allow farmers to voluntarily create a groundwater management plan to reduce water use. Once the plan is agreed upon, the state approves it and it becomes legally binding.

In 2012, Brownback sponsored legislation that allowed farmers to create Local Enhanced Management Areas, LEMAs, groups of farmers and irrigators who implement their own conservation plans. The state approves the plans but the law gives the state an out from dropping the hammer on farmers for depleting the aquifer excessively.

“It is much like an IGUCA (Intensive Groundwater Use Control Area), but the beauty is the locals can establish those measures, and the state doesn’t have to be heavy-handed,” Letourneau said.

The LEMA remains controversial in Sheridan County, and farmers are tired of publicity, Katherine Durham, manager of Groundwater Management District No. 4, said.

Jason Weimer, owner of the Six Toes Feed and Seed Store in Hoxie, also didn’t want to talk about it for fear of losing customers.

“I run a business,” he said. “I’m being straight up honest about it. I don’t want to get into the politics of it.”

On Jan. 1, 2013, Brownback announced the plan for 110 farmers in Sheridan and Thomas counties with great expectations that more farmers would be filing. Two months earlier farmers had been talking about forming a LEMA in Scott County.

The aquifer under Scott County and four neighboring counties that make up Groundwater Management District No. 1 is shallow, and a number of farmers already did not have enough water pressure left to irrigate. In 2012, the water table dropped 2.05 feet on average in one year, according to the Kansas Geological Survey.

“There isn’t an irrigator around here who doesn’t realize we have to do something or there won’t be enough water in five years to pump,” Ron Eaton of Scott City told the farmers and the local newspaper.

Jan King, director of the district, told the farmers if they agreed to a reduction the state would enforce action against those who over-pump according to the news article.

Over the next year and a half, meetings were held, and the farmers talked. They finally agreed to hold a vote on whether to reduce water use by 20 percent. A vote was not necessary, but a vote was important to determine that there was a consensus, said Greg Graff, president of the GMD. They also decided that instead of a simple majority, two-thirds would have to carry it.

People were engaged and wanted to do something,” Graff said. “When you are doing this, you want to do this right, and you want to have a good taste in your mouth.

Farmers argued over who could vote and whether each water permit should represent one vote. They also raised concerns that if they were not watering as much whether USDA’s crop insurance program would cover them.

Finally this spring the vote was held in Wichita, Scott, Lane, Greeley and Wallace counties. It failed to garner two-thirds of the vote but did get a majority.

Now farmers who want to conserve are planning more meetings, possibly redrawing boundaries of LEMAs and considering another vote, possibly next year, Graff said.

“I didn’t feel like it failed,” Graff said. “It passed by a slim measure. It was a beginning.”

More studies, meetings

Last year a Kansas State University study said if everything remains the same, the aquifer will be 70 percent depleted by 2060. But the study said the aquifer could last another 100 years if all farmers were to cut 20 percent of their usage.

Gov. Brownback issued a “call for action” and asked his administration to develop a 50-year vision of the future of water in Kansas.

“Water is a finite resource and without further planning and action we will no longer be able to meet our state’s current needs, let alone growth,” said Brownback, who was state secretary of agriculture in 1992, when the state board of agriculture created a task force to carry out the Kansas Ogallala Study Project.

Brownback’s vision was released in July and is chock-full of goals including reducing water use from the aquifer by 20 percent by 2065. Governor’s summits and community meetings were also suggested. Making Kansas a national leader on water issues was highlighted.

Letourneau, of the agriculture department, and his staff have been traveling Western Kansas to help educate farmers about the need to conserve water and share the draft vision plan. They’ve reached more than 10,000 people, he said.

“Their comments have been everything from 20 percent reduction, to that is too little, to 50 years is too late, to we need to do something right now, and leave us alone we are just fine,” Letourneau said.

The administration is putting together the comments and will present them at a conference scheduled in November.

The governor’s vision plan also discussed the possibility of a new water source for Western Kansas: the Missouri River.

The project would siphon water from the Missouri River from the northeast corner of Kansas in White Cloud and transport the water through a series of lift stations and canals past Perry Lake, through the Flint Hills some 360 miles into western Kansas.

Already Kansas and the U.S. Corps of Engineers have joined to pay $300,000 to fund a study to determine whether an aqueduct is viable. The study is expected to begin next year.

If approved, the project cost is estimated to range from $12.5 billion to $25 billon.

But trying to get a piece of the Missouri River could begin a new water war for Kansas. Other states, including Colorado, also want to grab some Missouri River water.

The aqueduct proposal “is the best and last long-term hope for water supply in the state of Kansas,” David Brenn, president of the Kansas Water Congress, said last year.

Mark Rude, executive director of Groundwater Management District No. 3, the largest district, said farmers in his district who oppose LEMAs have pinned their hopes on the aqueduct.

“This is an issue that is not a small one,” Rude said. “There are a lot of stakeholders — and no silver bullet.”