Vagrants and tree shade: Old ordinance books give insight into mid-1800s city life

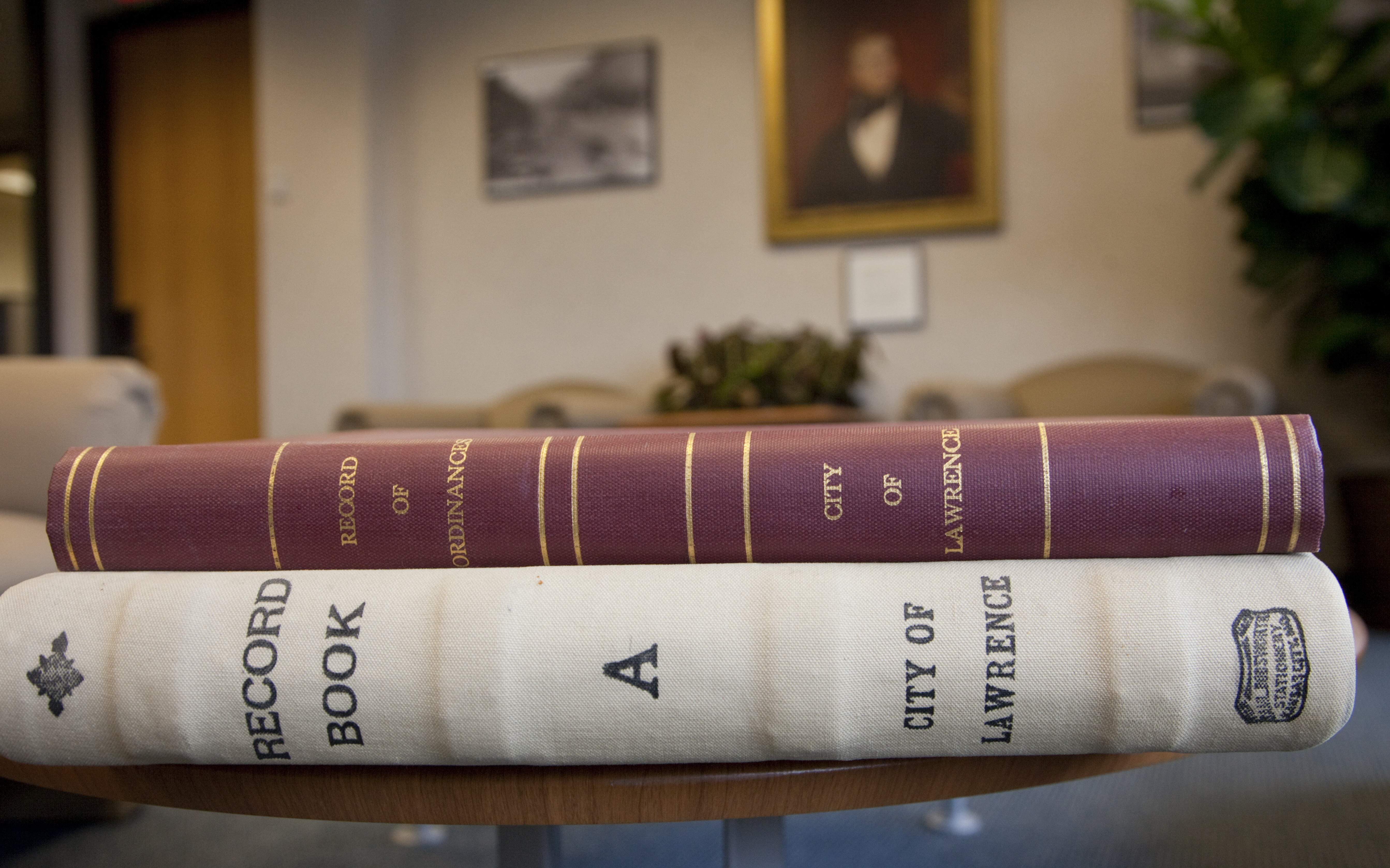

Jonathan Douglass, city clerk, looks through bound copies of old city record and ordinance books, some dating from 1854.

Bound copies of old Lawrence city records contain hand-written notes from City Council meetings and city ordinances dating back to the 1850s.

A hand-written page from a mid-1800s city record book lists several bills presented to the City Council. Included are bills for a burial of a pauper, a 75 cent charge for burying a heifer and the payment of .70 for a Mr. Otis Potter, “for hauling dirt on Massachusetts Street.”

Related feature

On Aug. 12, 1863, shade was a priority in Lawrence.

As the U.S. Civil War raged, evidently so did the heat. It caused Lawrence City Council members to take up their pens and craft City Ordinance No. 114, declaring that city residents were hereby allowed to build a fence five feet beyond any shade tree to provide it protection.

How do we know this? Simple. Lawrence’s official storybook tells us. Inside a locked storage room on the third floor of City Hall there’s a whole corner full of the books. Most of them are a good 18 inches tall and heavy. Inside many of them — the oldest ones — are line after line of handwritten ink.

They’re city ordinances. To make a law in Lawrence, you first have to pass an ordinance. And there is one thing about an ordinance that was true in the Horse and Buggy Age of the 1850s and the Electronic Age of the 21st century. An ordinance, according to state law, has to have a home in a book — a real, honest-to-goodness paper creation.

A database won’t do.

“They still all go into an actual book,” said Jonathan Douglass, Lawrence’s city clerk.

• • •

No, Lawrence City Hall isn’t quite a paperless society. City government does produce a lot less paper than it used to. For decades, the city would produce a paper City Commission agenda packet that, even on a slow week, was normally at least an inch thick. Take that times five commissioners and numerous staff members, and you can begin to hear the trees cry for mercy. Now all that information is online.

But even if City Hall never produced another scrap of paper, just keeping all the files it already has accumulated would be quite a chore. There are personnel files, there are invoices, there are meeting minutes, and surprisingly there are lots and lots of building plans.

Douglass estimates the city has more than 2,000 copies of large, rolled building plans. They’ve been submitted with building permits over the years, and the city believes it’s important to keep them in perpetuity for historical and other reasons, although Douglass is exploring electronically scanning many of them. Thankfully such plans are now required to be submitted electronically.

Building plans, ordinances, meeting minutes, resolutions and some personnel records are on the list of documents that never get thrown away. Many others, though, are allowed to be trashed after a certain numbers of years.

That, however, doesn’t mean they always get thrown away on time. Douglass can attest to that. His office has spent about one day per week from July through the end of this year sorting and destroying old records stored in the city solid waste facility in North Lawrence.

At the end of the project, Douglass sent 1,289 cubic feet of documents — about 880 boxes — to a private company where they’ll be stored for 17.5 cents per cubic foot per month.

He shredded 9,283 pounds of documents.

• • •

Some things never change. Even in the mid-1800s, some of the issues city government dealt with were similar to those of today. Well, sort of.

• Sidewalks. An ordinance in September 1859 might be the first in Lawrence authorizing sidewalks to be built. And just like today, the city was emphatic that it is the property owner’s responsibility to maintain the sidewalks, not the city’s. Actually, they were pretty serious about it. The city marshal was instructed to look for broken sidewalks and notify the adjacent property owner. If the repair wasn’t made within 48 hours, the city would fine you $5. In 1859, that was the equivalent of about $120 today, according to an inflation calculator.

• Speeders. In January 1863, people must been out of their mind. Speeding. Speeding, I say, on bridges. It got to the point that the city had to make a law making it illegal to drive any horse or horse-drawn vehicle “faster than a walk” on any bridge in the city.

• Nuisances. Presumably, loud stereos and Lady Gaga were not something the city fathers had to deal with. Instead, when they wrote an ordinance titled “Nuisances” in 1863, it included 10 sections related to the disposing of dead animals on the ground and animal excrement. Maybe Lady Gaga is not looking so bad after all.

• Vagrants. If there was one thing you didn’t want to be labeled as in 1863, it was a vagrant. The city spelled out in an ordinance that any person “found to be loitering, wandering or loafing about dram shops, saloons, restaurants or any other place by day or night without any visible and lawful means of support shall be deemed a vagrant.” The first offense came with a minimum $1 fine, the second offense a minimum $5 fine and the third offense a minimum $25 fine. In case you’re wondering, that’s equivalent to about $440 per day. Now get back to work.

• Rocks. And then of course there was this: In November 1858, the city declared that all persons shall be prohibited from “hauling or carrying away” any rock from the fort on Capitol Hill. Pesky kids. They never change. Always stealing rocks. And, no, City Hall staffers don’t know where Lawrence’s Capitol Hill is either. Technically, the ordinance is no longer in force, but they would prefer that you kids keep your hands off the rocks.

• • •

When City Manager David Corliss hired Douglass as city clerk, he did not ask a question that surely would have been high on the list of requirements for a 19th-century clerk.

“He didn’t ask me about my penmanship,” Douglass said.

Without good handwriting in the mid-1800s, your days as city clerk likely would have been limited. The handwriting — line by line in black ink, except for occasional red underlines — still draws a lot of attention.

“Look at how beautiful that is,” one City Hall staff member said while looking at an open ordinance book. “Why don’t people write like that anymore? Look at that ink on the downstroke.”

Others were less fascinated.

“That makes my hand hurt thinking about all that writing,” Assistant City Manager Diane Stoddard said.

Regardless, the book still draws a crowd when it is pulled out for examination. These days that is not often. Even the newer books aren’t used much. All new ordinances also are maintained in an electronic database and kept online.

But the books remain, just in case. For Douglass they often bring to mind one thought.

“I don’t know how they did this without computers,” he said.

• • •

Back to the shade trees and fences to protect them. On Aug. 12, 1863, it is not surprising that protection was on the mind of Lawrence residents. But of shade trees?

The last ordinance entered into the book on Aug. 12, 1863, had a subject that seemed more likely. Ordinance No. 115 clarified that the city marshal indeed had the power to arrest anyone for violating a city law. Perhaps residents had an inkling of what was to come.

Just nine days later, on Aug. 21, 1863, the greatest tragedy in the city’s history struck. William Quantrill and his band of raiders burned the city and killed more than 150 residents.

For the next eight months, Lawrence’s official story book fell silent. Not one official law passed in Lawrence during those dark days. Sometimes what’s not written says a lot, too.

Then, on April 30, 1864, some city clerk grabbed his pen and wrote again. The topic of the new law: regulating the sale of intoxicating liquor.

What? It is Lawrence’s storybook after all.