Noble struggle: Graphic novelist Clowes mines life for art

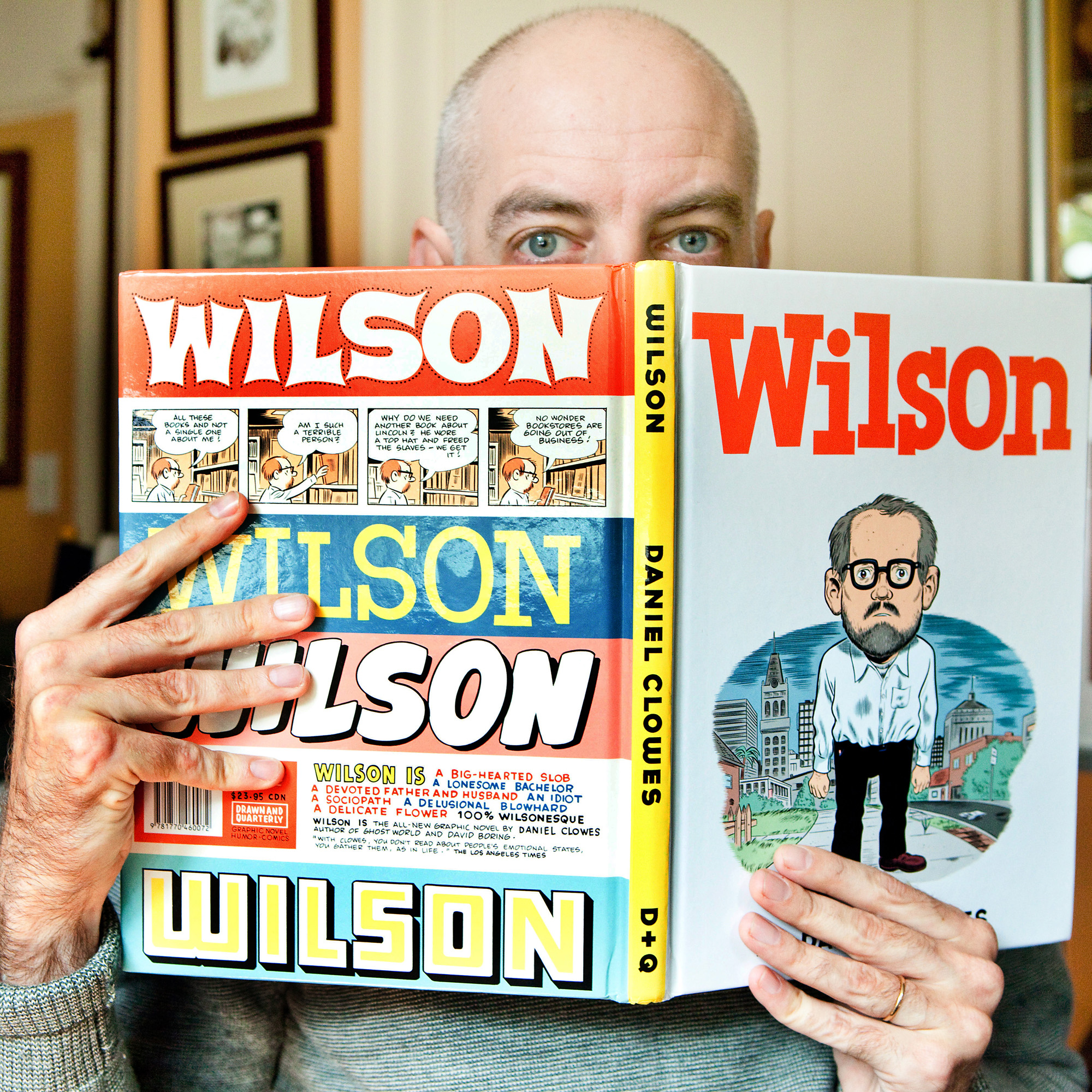

Daniel Clowes, at his home in Oakland, Calif., shows off his latest graphic novel, “Wilson.” It features a character who hangs around the coffee shops on Oakland’s Grand Avenue, verbally sucker punching strangers with whom he instigates one-sided conversations.

Oakland, Calif. ? In the mind of cartoonist Daniel Clowes, the modern egoist is a balding, middle-aged schlub named Wilson.

Lonely and self-loathing, Wilson, the subject and title of Clowes’ latest graphic novel, hangs around the coffee shops on Oakland’s Grand Avenue, verbally sucker punching strangers with whom he instigates one-sided conversations. He is rude, neurotic and opinionated.

Yet you can’t help but like the guy because he is also honest, funny and desperate to better his circumstances.

“Wilson” (Drawn and Quarterly, $21.95) is the latest in a cartooning career built around antagonistic protagonists who operate on a somewhat higher level of consciousness — and pay the price. Among such memorable Clowes characters are “David Boring,” the passionless, self-alienating antihero, and Enid Coleslaw, the angst-ridden, morbid teen in “Ghost World,” the seminal graphic novel that became a cult film and earned Clowes an Oscar nomination for best adapted screenplay.

“I find malcontents to be amusing,” Clowes says on a recent morning in his Oakland backyard. He lives on a tree-lined block with his wife, Erika, 6-year-old son, Charles, and emotionally needy beagle, Ella. “I have a lot of friends who are cranky complainers, and I guess I have a high tolerance for that.”

Given the cartoonist’s predilection for dark characters, you’d expect him to be the biggest grouch of all. Sorry to disappoint. The picture of poise and Midwestern manners (he was born and raised in Chicago), Clowes, 49, is beyond nice. Tall and slender with light blue eyes, he is warm and inquisitive, and he remembers the names of fans who wrote him 20 years ago. He keeps their letters in a box above his desk.

Clowes, an illustrator for The New Yorker, is traditional in other ways, too. At a time when print is down and young cartoonists are turning to the Web, Clowes still draws everything by hand — “I’ll never type in a URL to look at comics,” he says — and he was so shaken when Cody’s Books closed in Berkeley, Calif., that he relates it to how a Catholic would feel if the only church in town shut its doors.

“That (book store) was the focal point of my life,” Clowes says.

Like many of his characters, Clowes spends his time in local spots. He wrote and drew “Mister Wonderful,” The New York Times comic strip, at Posh Bagel on Piedmont Avenue. Most of “Wilson” came to life at Jennie’s Cafe on Grand Avenue.

After his father’s death, Wilson realizes how alone he is in the world. So he forces a reunion between himself, his ex-wife and the teenage daughter he never knew he had. The three don’t exactly hit it off, but you can’t help but root for Wilson. Here is a cynical loner who counts his dog as his only friend. Yet he desperately wants to find human connection. Even if he has to manufacture it.

“Wilson has a noble struggle,” Clowes says. “He is trying to get something bigger out of his life. He’s expecting other people to live up to his vision of how things should be, and they don’t.”

Inside the character

Clowes and Wilson share more than a zip code. It was in a suburban Chicago hospital that Clowes came up with Wilson two years ago. His father was dying of lung cancer, and, like Wilson, Clowes was by his dad’s side. To pass the time, Clowes doodled dozens of comic strips — mostly stick figures and dialogue balloons — until Wilson popped into his head.

“By the end of the week, I felt like I knew this character,” says Clowes, who calls Wilson an exaggerated version of himself. “You’re always looking for a character who can take you on an adventure rather than forcing them to go somewhere. He was like a real guy. I feel like I’ve seen him walk by while sitting at the cafes on Grand Avenue. He might be an ex hipster. Maybe he dropped out of Cal.”

The graphic novel is arranged in single-page strips with punch lines (usually delivered by Wilson at someone else’s expense). Clowes drew Wilson in multiple styles that play off each other: Sometimes he’s a realistic man with back hair and a beer gut. Other times he’s squat and cartoonish with dots for eyes.

“I wanted each strip to have its own presence and integrity and subtle, tonal shifts,” he explains. “They are like one-page jokes, but the punch line is almost tragic. Sometimes it’s not a punch line. It’s almost the opposite of one.”

Break from isolation

Clowes attended the Pratt Institute in New York and graduated in 1984. He began his career as an underground cartoonist with the detective comic book “Lloyd Llewellyn.” In 1989, he created his seminal series “Eightball,” which cemented his role as a leader in the comics world. He is the only cartoonist to have won the Eisner, Ignatz and Harvey awards, top honors in the world of comics, as well as the Oscar nomination.

Clowes moved from Brooklyn to Berkeley in 1992, settling in Oakland in 2000. He found a new fan base in 2001 when he and director Terry Zwigoff adapted “Ghost World” into a movie starring Thora Birch and Scarlett Johansson. In 2006, Clowes and Zwigoff collaborated on “Art School Confidential,” also based on a Clowes comic and starring John Malkovich and Jim Broadbent. His next project, “Megalomania,” is an animated teen film directed by Michel Gondry. Actors Seth Rogen and Steve Buscemi will supply the voices.

Even though Clowes is hardly the Hollywood type, he enjoys collaborative screenwriting as a break from his own solitary work. Not that Clowes minds working alone. But the best advice he ever got about cartooning came from artist and illustrator Robert Crumb, who told him to take an occasional hiatus from cartooning.

“He told me that (in cartooning) you hit 50 and realize you’re talking to yourself and you’re nuts,” Clowes says. “So he said to find something else and get away from cartooning for a while. That way when you come back to it you can really appreciate it.”