Harvey Houses on the prairie: How a Kansas man pioneered the hospitality industry

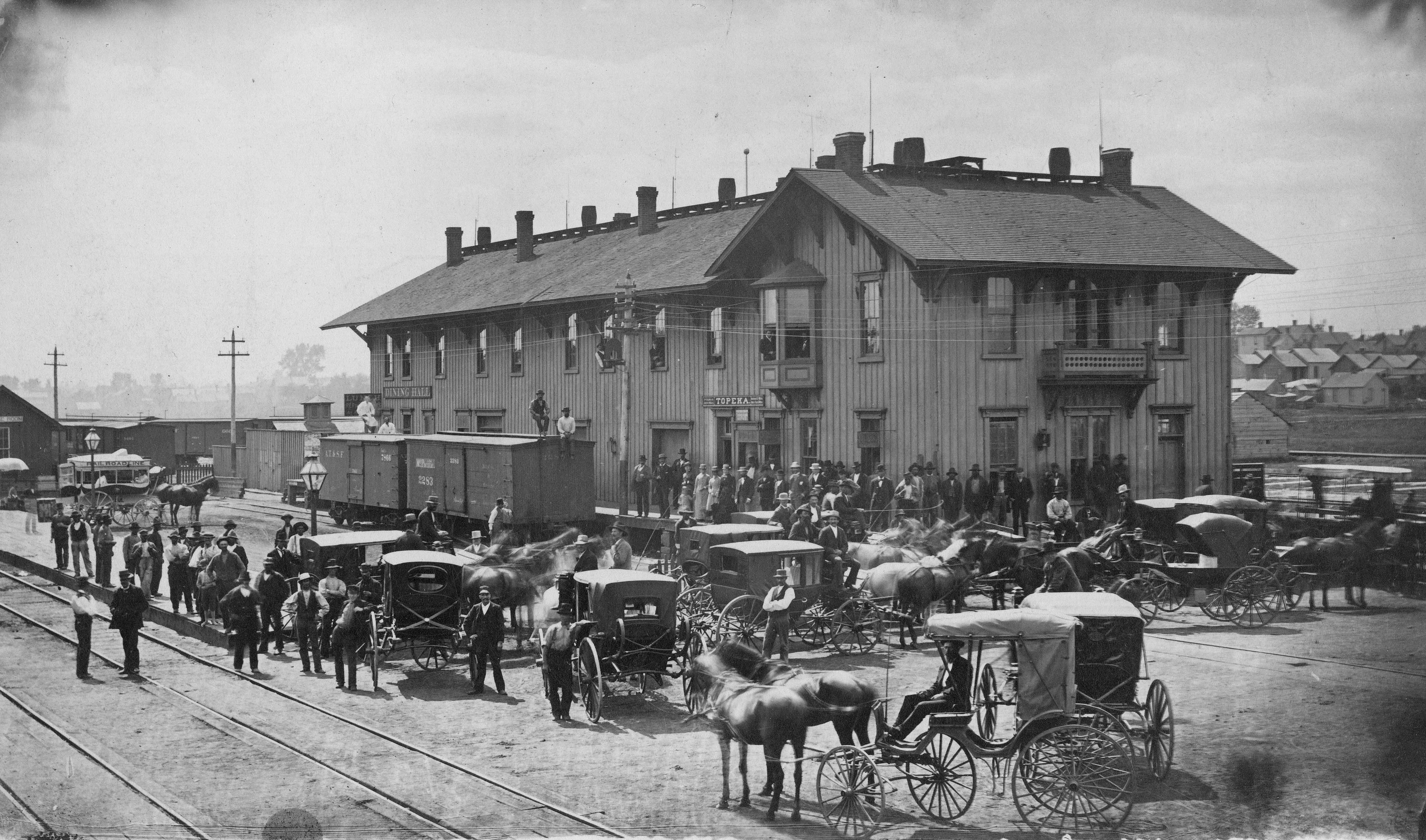

The Topeka Depot of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, where Fred Harvey took over the second-floor lunchroom in early 1876.

Author Stephen Fried.

Little-known fact: Lawrence was at the epicenter of a revolution in global capitalism.

When America was 100 years old, and Kansas was just 15, the economy was, of course, built around agriculture and manufacturing. The service-based economy of today was as inconceivable as credit cards or the Internet.

Then came along Fred Harvey of Leavenworth.

His pioneering vision for customer service would set the stage for the service empires of today such as Hilton, Marriott and all manner of restaurant chains, says Stephen Fried, author of “Appetite for America,” the first-ever biography of Harvey.

Fried’s whistle-stop book tour on the Southwest Chief makes three stops in Kansas City and Topeka, including a talk and book signing at 4 p.m. Friday at the Kansas State Historical Society.

Like his book, Fried’s talks will set Harvey in the context of a little-known yet defining period of American history.

“I think of them as the ‘fly over’ years — between the Civil War and the Depression,” Fried says. “It’s really an amazing chapter of American history that most of us slept through in school.”

Much of Harvey’s legacy was previously scattered around many collections across the country as well as hidden away in Harvey family records. That might explain why a biography of Harvey had never been written, says Lin Fredericksen of the Kansas State Historical Society.

Her Topeka-based archive has quite a bit of material that Fried drew from for his book.

“It was a long process — I believe we corresponded off and on for over a year and a half,” Fredericksen says. “I was very impressed with his depth of knowledge.”

Pioneering vision

In 1875, the finer appointments of civilization were few and far between. You could dine on, say, oysters and fresh vegetables with silverware served by a waiter in New York City or Chicago or Los Angeles, but not likely anywhere on the road in between.

Especially not in Kansas.

“Kansas was the West then — that was the end of America. There was the America that went to Fort Leavenworth, and then there was California,” Fried says.

As a railroad man who traveled constantly, selling and delivering freight around the country, Harvey knew all too well how rough life on the road was.

“One of the things he realized on these trips — because he had a really bad stomach — was that the food and the service on these trains and track-side restaurants was horrible. It was abhorrent. People talked about it all over the country, but they talked about it like something that could never be fixed,” Fried says.

Harvey was in a unique position to do something about it. He parlayed his railroad contacts and his familiarity with sellers of all kinds of goods from around the country into the first Harvey Houses in 1875 — one of which was in Lawrence.

“Since the Lawrence one is closest to Leavenworth, it’s most likely that that’s the one they worked on first,” Fried says. “If Lawrence wanted to claim its Fred Harvey heritage, it certainly could.”

Stunning things in remote places

By the turn of the century, Harvey had fully developed his new business model and was well under way building a hospitality empire.

Railroad towns all along the dusty route from Chicago to California suddenly had first-class hotels and restaurants, 30 of which were in Kansas.

Harvey Houses were stunning things to have in such remote places, Fried says. A typical one “looked like it should be in Chicago or New York City, if it existed at all. It seemed like it was a mirage.”

The Harvey Girls of Syracuse stand for a portrait.

Fine tablecloths, real silverware, crystal, glistening coffee urns and the famous Harvey Girls — the first female work force in America — whose service was impeccable yet swift.

“It was an amazing thing to watch. People talked about just being able watch it — it was like ballet, to watch these waitresses and chefs at work,” Fried says.

“They had to be able to serve a perfect gourmet meal in … the train breaks — only 30 minutes.”

Suddenly small-town America could get fresh vegetables from California, fresh fish from the Great Lakes, oysters from the Pacific — all kinds of goods that the Harvey Houses stocked from refrigerated cars straight off the trains.

“You can’t overestimate what it was like to have a Harvey House restaurant in a town where, before, there might have been a little restaurant that wasn’t able to serve fresh food because they couldn’t get it,” Fried says.

That’s one of Harvey’s legacies celebrated by foodie and widely read journalist William Allen White. On Feb. 14, 1901, he wrote in the Emporia Weekly Gazette:

“Fred Harvey, who is dying, has lived a useful life. He has done more to promulgate good cooking — healthful, substantial, wholesome, digestible cooking — in Kansas than all the cook books ever published … Fred Harvey was a greater man than if he had been elected to something. The Gazette hereafter will pay more attention to men out of politics.”