Walking ahead: Postal carrier overcomes polio, accident to deliver mail

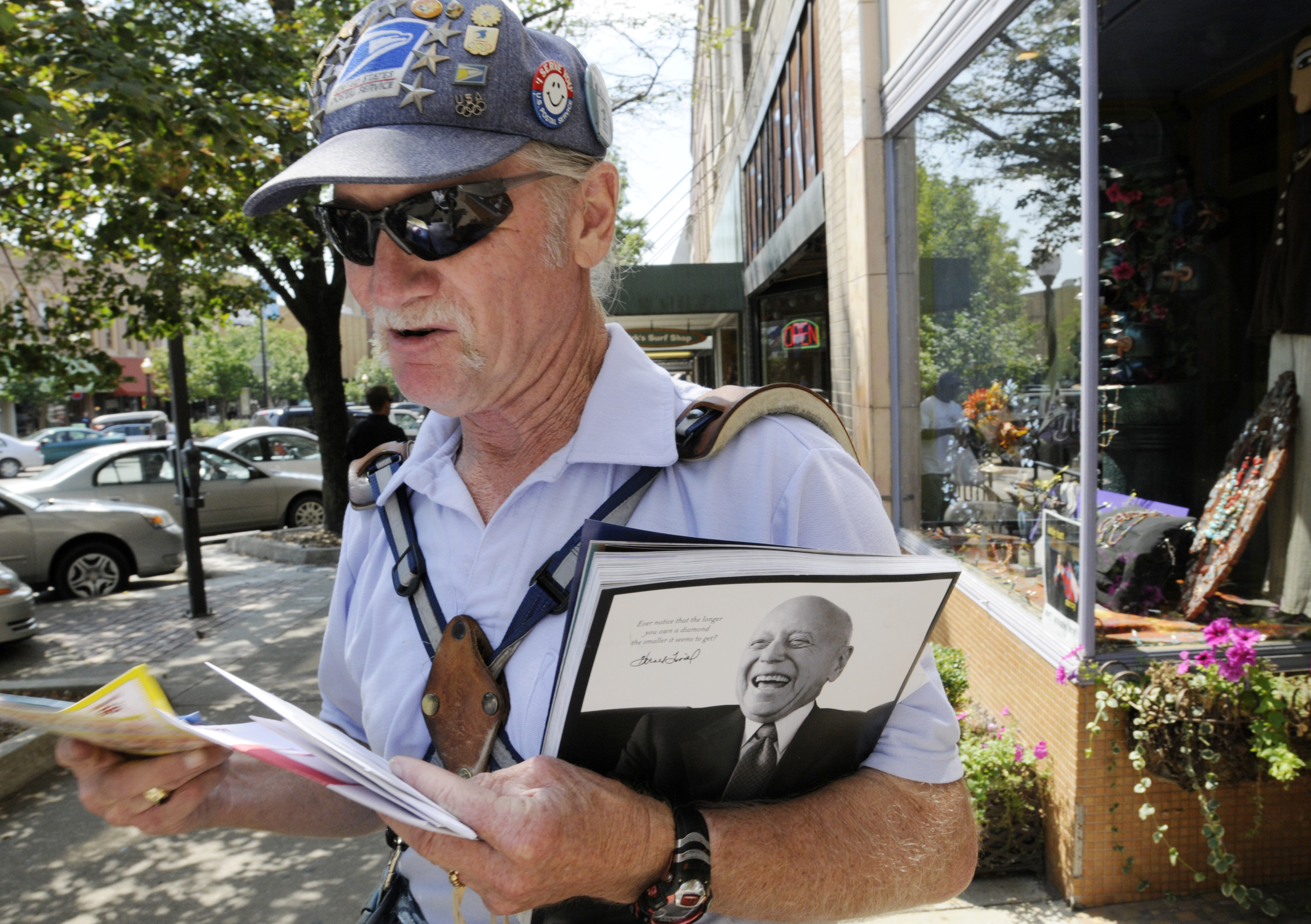

Jerry Totten completes a mail delivery at Mark's Jewelers, 817 Mass. Totten is Lawrence's only full-time, walking mail carrier, and his route includes most of downtown.

Jerry Totten makes his mail deliveries Tuesday, to addresses along Massachusetts Street. His route is Massachusetts and New Hampshire streets from the 600 to 1100 blocks.

Jerry Totten, 51, is a survivor. He’s defied death on two occasions and is Lawrence’s only remaining full-time, walking mail carrier. He admits he’s lucky to be walking at all.

Totten contracted polio when he was 2 years old. “I don’t remember it personally,” he says. “My parents told me about it. They thought I wouldn’t survive. I was in the hospital a long time.”

He defied the odds but it took him two years to learn to walk again.

He left his family’s farm in Jewell County in 1969 to study journalism at Kansas University and worked part-time at the post office. He graduated in 1972 and turned down a newspaper job when he discovered journalists earned half as much as postal workers.

“I loved Lawrence, especially the downtown, (and) needed good money and benefits, so I accepted a full-time post office job,” he says.

“Later I considered pursuing journalism again, but in 1978 the postal carriers’ union negotiated a contract ensuring postal workers wouldn’t ever be laid off. It was great job security and I loved my co-workers so I stayed.”

He became vehicle maintenance operator but yearned to be outside in the fresh air. When the downtown walker retired in 2002, Totten got his dream job delivering mail along Massachusetts and New Hampshire streets between Sixth and 11th streets. He says it’s been the best six years of his life, in spite of the fact that it includes his second brush with death.

On Feb. 1, 2007, a car plowed into Totten on the crosswalk at New Hampshire and Seventh streets. He sustained severe head injuries, bled profusely and was airlifted to the Kansas University Hospital.

“I don’t remember anything about it. Other people told me what happened. I couldn’t have transfusions because of the brain swelling,” he says matter-of-factly. “When I woke up four days later I got three units of blood.”

He disliked being in intensive care.

“I felt caged,” he says. “I was tied to wires and machines. I got them taken off so I could get to the bathroom by myself.”

Then he asked to walk around.

“Medical staff said I couldn’t walk around in intensive care,” he says. “So I asked to be moved to another room, but there weren’t any available because of massive reconstruction.”

By the seventh day he’d had enough.

He asked his wife, Joda, assistant to the associate dean at the KU School of Engineering, to bring his clothes (the one’s he’d been wearing had been cut off after the accident).

“She was a little upset and shocked,” he says. “The doctors told her I needed 24-hour care and she wasn’t ready for that. Joda was still coming to terms with my injuries, but I was ready to move on.”

The doctors succumbed to his demands for release, made arrangements for therapy at Lawrence Memorial Hospital, and made a check-up appointment for March 7.

He told them he couldn’t keep the appointment because he’d be back at work by then; they gave him an earlier one.

Had the head injury affected his judgment?

“No. I was just determined to recover and didn’t want to dwell on my injuries,” he says.

At his February 28 appointment, the doctors were astonished by his progress and his determination to start work just four weeks after he’d knocked on death’s door.

“They gave in but said I couldn’t drive until I’d passed another test,” he says. “I promised to be a good boy and let others drive me to work. I passed my test a week later.”

Totten is deaf in one ear and still has short-term memory challenges as a result of the accident.

“I’ve learned to adjust,” he says. “I write myself notes all the time.”

He returned to walking his route with some trepidation, but he was determined to conquer his fear. He carries an air-horn with him.

“Some drivers don’t pay attention to lights at crossings,” he says. “My honking horn soon makes them take notice.”

He received a great outpouring of community support after his accident and people still tell him he’s an inspiration.

He smiles and says, “I’m just glad I’m still able to keep doing the job I love.”