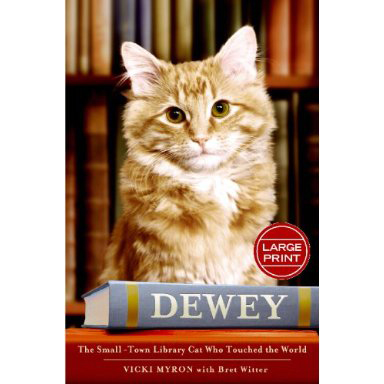

Library life: ‘Dewey’ chronicles experiences of author, cat, town

Vicki Myron, co-author of Dewey,

Des Moines, Iowa ? He was a yellow tabby with twinkling green eyes, who arrived in the overnight drop box of a farmland library one frigid January night. Dewey Readmore Books became the library’s star boarder and an international celebrity.

Now he’s the subject of a best-seller that chronicles the struggles of the library worker who found the trembling kitten, the town that embraced him and Dewey himself.

“Dewey, the Small-Town Library Cat Who Touched the World,” by Vicki Myron and Bret Witter, has 336,000 copies in print and has quickly climbed to the top 10 on The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Publishers Weekly and other lists of best-sellers.

“It has great appeal,” Paul Ingram, buyer at Prairie Lights bookstore in Iowa City, says, comparing it to the hugely popular “Marley & Me,” about the joys and headaches of a difficult Labrador retriever. Ingram says that “Dewey” attracts an odd mix of pet lovers and history buffs thanks to its weaving of the cat’s exploits with the history of a small town and Iowa.

Myron decided to include more in her book than just the story of Dewey because the town, the cat and Myron herself were closely linked. “When we tried to write just a cat book it didn’t work. We had to tell the whole story for it to make sense,” she says during a break from a book tour in Des Moines.

Dewey, named after the Dewey Decimal System used by libraries to catalog books, quickly became well-known in Spencer, a farm town of about 11,000, although no one is sure why the rest of the world cared about him. But they did. Writers and TV crews came from as far away as Japan to the plains of northwest Iowa to see Dewey.

“It’s very hard to put into words,” Myron said. “I always called it Dewey’s magic because there is no other word for it.

“When people met Dewey … they went home and told all their friends and neighbors about it, or kept articles about him or wrote an article. We would get weekly newspaper articles from little towns all around the United States that people had shared his story and it had made the newspaper and those people never forgot,” Myron says.

Old soul

Dewey was discovered in the Spencer library’s overnight drop box in January 1988, a time when Iowa was in the midst of an economic chill that had gripped the nation. Spencer is a town that hasn’t changed much since the 1930s, with a downtown of family-owned stores in connecting two- and three-story brick buildings, a second-run movie theater and The Hen House, which sells decorating items to farmwives.

Myron bonded immediately with Dewey as she lifted the tiny kitten from the book drop that January morning.

“He was so cold and half-starved and very dirty. He didn’t look like much until I picked him up and he started purring immediately and he looked in my eyes with his eyes,” she says. “He had the most gorgeous eyes I had ever seen, and I felt a connection with him right away.”

A petite woman with thick, short brown hair who wears wire-rimmed glasses, Myron was struggling back then to make ends meet – a divorced mother trying to raise a daughter, working full time at the Spencer library and studying to get her master’s degree. She had only been on the job for six months and had wanted to make the library more homey. Dewey would fit right in.

Patrons took to him quickly, and over time visitors increased from 60,000 a year to more than 100,000. Many were suffering from the crippling economy that hit the farming community especially hard, and Myron thinks Dewey lifted their spirits and made them a bit more eager to stop off at the library.

“Dewey didn’t bring jobs to Spencer, but there were a lot of farmers who came in to fill out the first resume of their life. They didn’t know how to use the computer, they were having a tough time and were really down when they came in. Dewey won them over and put a smile on their face,” Myron says.

“He … was something to be proud of when Spencer didn’t have a lot to be proud of.”

She described Dewey as an “old soul.”

“You could see down into his soul through his eyes and he would look at you the same way,” she says. “It was his personality: He was so loving and mellow. He didn’t care who you were.”

Two of Dewey’s best friends were homeless men who would stop by the library.

“They never spoke to us but they would pick up Dewey and talk to him for 20 minutes. I don’t know what they said. It didn’t seem to matter, but it made them feel better,” she says. “He also seemed to know who needed him more than others.”

Saying goodbye

Dewey died on Nov. 29, 2006, at age 19. Since then, the library has received more than 100 offers for a new Dewey, but the library board decided to wait at least two years before deciding whether to get another cat, says Myron, who retired at the end of last year.

She recalls how Dewey’s health began to fail in the year before he died and how, to help him put on weight, she would feed him cheese, scrambled eggs and roast beef sandwiches. “And he loved it!”

On the day Dewey died, Myron was about to leave for a trip to Florida when she got a call from the library staff telling her Dewey wasn’t acting right.

“He was fine when I left, or I thought he was, but when I went back down there I could see he was in pain,” Myron says. An X-ray at a local vet showed he had a large stomach tumor. She stayed with Dewey as he was put to sleep.

“It was heart-wrenching,” Myron remembers. “I called all the staff and they came out to say goodbye, but it was one of the most difficult things I have ever done, but I knew I had to do it because he was suffering and I’d never let him be in pain.”

His ashes were buried in the lawn outside the library. A granite marker was placed at the site.