City’s waste not wasted

Biosolids used to fertilize area crops

A truck from Nutri-Ject of Hudson, Iowa, dumps biosolids on a field farmed by Roger Pine in North Lawrence. Biosolids from the city of Lawrence are put to use on area cropland as fertilizer.

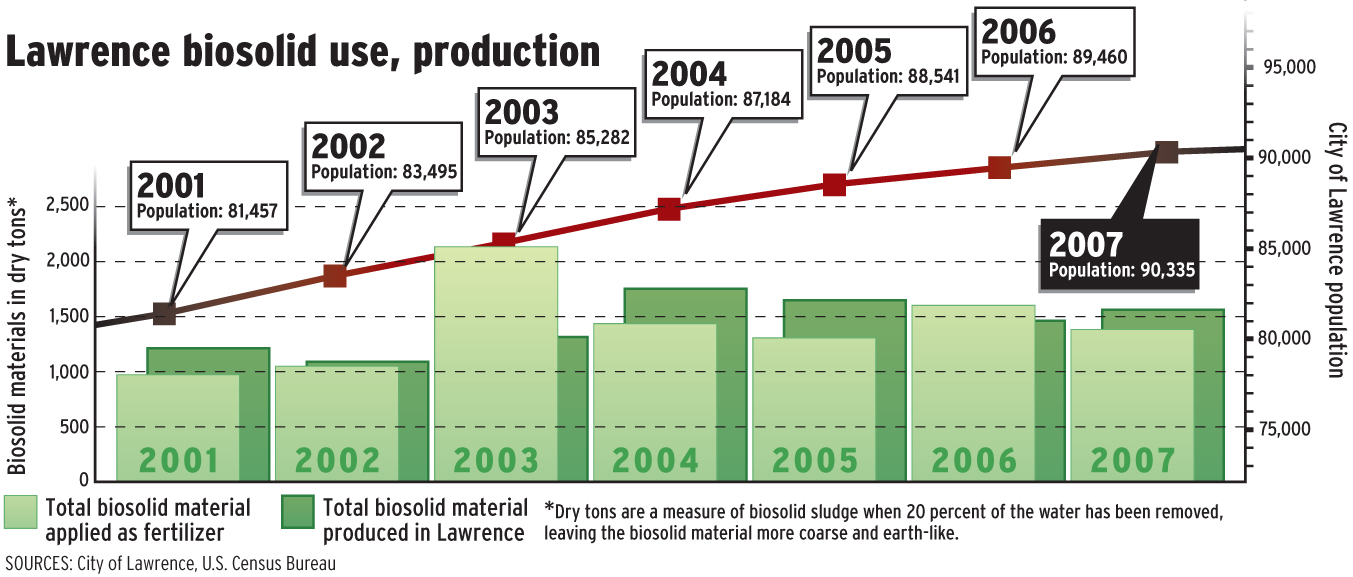

Lawrence biosolid use, production

It might be overstating it to say what is Lawrence’s trash is Roger Pine’s treasure.

But the large piles of biosolids being dumped by the semitrailer load on the farmer’s corn fields last week definitely were appreciated.

The piles – which look like fine, black topsoil – originated from what the homes and businesses of Lawrence flush down the toilet and wash down the drain. Of course, there are about a half-dozen steps that transform the waste collected in sewer pipes to the fertilizer applied on farm fields.

Pine is among the farmers who benefit from Lawrence’s biosolids program. The biosolids (basically refined sewage sludge) boost the nitrogen and phosphorous levels in the ground and add to its organic matter.

For Pine, it is a true win-win proposal that keeps the city from having to unload its waste into landfills.

“Even though it might not smell good, it is something that is good for the ground and helps fertilize the crops,” Pine said.

For more than 50 years, the city has had some form of biosolids available for its residents to use.

In the mid-1970s, the city applied biosolids to the fields it owned around the plant. In the early 1990s, it began working with farmers.

Along with what is applied on cropland, the city has higher-grade biosolids that anyone can use on gardens and lawns.

“It’s basically recycling,” said Jeanette Klamm, the city’s utilities program manager.

Safety concerns

The use of biosolids – and its safety – was called into question early this year when a federal judge ordered the U.S. Department of Agriculture to compensate a Georgia farmer after biosolids from a municipality poisoned his fields.

According to The Associated Press, the land was filled with arsenic, toxic heavy metals and PCBs that exceeded federal health standards by two to 2,500 times. Hundreds of the farmer’s cows died.

Joseph Mendelson, legal director for the Center for Food Safety, called the judge’s decision a landmark ruling.

“I think it is significant that the court makes the finding that land application damages and in fact causes harm to farmland and animals,” he said.

The Center for Food Safety, a Washington, D.C.-based public interest and environmental advocacy group, is against the use of what it calls sewage sludge on cropland. Even treated sludge could contain pathogens, industrial wastes, heavy metals and residue from antibiotics and other drugs, Mendelson said.

“There is no question that proponents of this technology say that it is somehow better to recycle this stuff, but you know we don’t recycle hazardous materials, and we don’t want to create a new environmental problem,” Mendelson said.

For food to be certified as organic, biosolids from municipal sewage plants can’t be used, said Rhonda Janke, associate professor of sustainable cropping systems at Kansas State University.

“A lot of organic standards follow the precautionary principle that it’s better to err on the side of caution, of being too safe, rather than not safe enough,” Janke said.

Besides the organic label, there isn’t any way for U.S. consumers to tell whether food has been grown using biosolids, Janke said.

While Janke doesn’t have a problem with biosolids fertilizing shrubs, trees and lawns, she doesn’t think they belong on crops to be eaten by humans or animals.

“You just never know. It seems like the more research we do, the more we learn how these things really work,” Janke said.

The final product

At the Lawrence Wastewater Treatment Plant, an open-air concrete building holds six months’ worth of the city’s biosolids. It’s everyone’s waste – about 90,000 of us in Lawrence – since November reduced to what would cover roughly 150 football fields.

On an overcast spring day, standing on a catwalk above this stockpile of refined sewage, the smell is not breathtakingly awful. Rather it’s an earthy, musty odor.

About twice a year, these storage units get cleaned out and their contents spread on fields in a 10- to 20-mile radius of Lawrence. They usually end up on soybean, wheat or corn fields. Sometimes – if the biosolids are applied in the summer – hay fields will receive them.

The city produces about 7,000 tons of biosolids a year.

Above average

The operation in Lawrence – a nationally recognized one – is removed from the questionable practices that were occurring in Georgia, said Klamm, of the city’s utilities department. As part of an environmental management system, the city’s testing and treatment goes beyond what the Environmental Protection Agency requires.

Before it ever lands in the field, the biosolids have gone through a multiple-step process including one that has microorganisms eating away at solids, killing off disease-spreading pathogens.

The final product is sent to an outside lab to be tested for 10 metals (zinc, lead and copper are among them). The city has never seen its levels come close to the EPA’s allowable limit. And the city’s industrial sites are required to treat wastes for those toxic metals before they reach the sewage plant.

“Lawrence is very, very residential compared to other cities, and we have an active pretreatment program, so our metals are very low. A lot of times, they are not detected (in the sludge),” Klamm said.

When the biosolids are ready to go on fields, soil samples are taken to make sure the right amount of nutrients are applied.

The Kansas Department of Health and Environment tests the Lawrence facility at least four times a year for heavy metals, pathogens and odor, KDHE spokesman Joe Blubaugh said. It is one of more than a hundred municipalities in the state the puts biosolids on fields.

On top of testing and treating, Klamm said EPA has requirements on what fields can take the biosolids. They can’t be too close to rivers or ponds.

And if farmers plant crops that grow underground (such as carrots or beets), they have to wait one to three years before harvesting. Klamm said Lawrence doesn’t touch the produce crops.

The restrictions for biosolids are far greater than those for farmers who just use the livestock manure as fertilizer, a practice that is largely unregulated, Klamm said.

Nothing goes to waste

Pine doesn’t see any hazard with using the city’s biosolids, and neither do the landlords who own the land he farms. Along with what the city tests, he has had scientists from Kansas State University test the soil for heavy metals.

“If it was a heavy-metal type of product, we wouldn’t be interested,” Pine said.

The majority of Pine’s corn goes toward feeding livestock or making ethanol.

DeAnn Presley, an environmental soil scientist with K-State Research and Extension, said she believes using biosolids on fields is a good way to make sure wastes don’t go to waste.

“Agronomists and engineers alike agree it’s better to apply and get some good out of it than to put it in a landfill and never get any good out of it,” she said.

It’s a program that saves the city money. Storing the biosolids at a landfill would cost around $300,000 a year. Right now, the city is paying the Iowa-based contractor Nutri-Ject $80,000 to $100,000 to haul and spread the biosolids.

The city is in the enviable position, Klamm said, of having farmers more than willing to use its biosolids. They have a list of about eight to 12 who are regularly in the program.

Klamm said research has been done by almost every land-grant university that shows the process is a safe one.

Presley predicts that in the coming decades – after farmers have used biosolids on fields for 30 or more years – municipalities will have to look for new ways to reuse it.

Presley is working to rewrite the extension’s publication on the use of biosolids. The document will be useful for the neighbors of biosolid-using farmers.

“If you first hear biosolids and there is metals in it – that sounds awful, but then again there are metals everywhere in our world,” Presley said. “So (the concern) is at what levels and is it regulated?”