Safe and warm

Philip Roth enters the Library of America

Warren, Conn. ? Philip Roth, the author of “Portnoy’s Complaint,” “American Pastoral” and many other novels, has lived more than 30 years in the Connecticut countryside in an 18th-century farmhouse, where the late summer air is deep and calm, disturbed only by crickets and the occasional passing car.

At times, he could have used a house that screens out more than bugs. Over the past half century, he has been accused of anti-Semitism and obscenity; found himself relentlessly, and unfavorably, compared to the characters in his books; survived heart surgery and a nervous breakdown; endured two contentious marriages, the latter to actress Claire Bloom.

But his mood is light today and the news of late has been welcome: Roth is the youngest living author to be given solo billing in the Library of America, which issues hardcover collections of the country’s most acclaimed writers. The first two volumes, covering his work through the early 1970s, are out this fall.

“He is a great artist,” says critic Harold Bloom. “He may be the finest artist among American writers since William Faulkner and Henry James. There’s the endless variety of modes he works in. His style, his stance, his point of view.”

In the best sense, the Library of America project is like witnessing one’s own memorial. The library’s books are traditionally dedicated to dead writers or to those no longer active, such as Eudora Welty and Roth’s close friend, Saul Bellow, who died last spring.

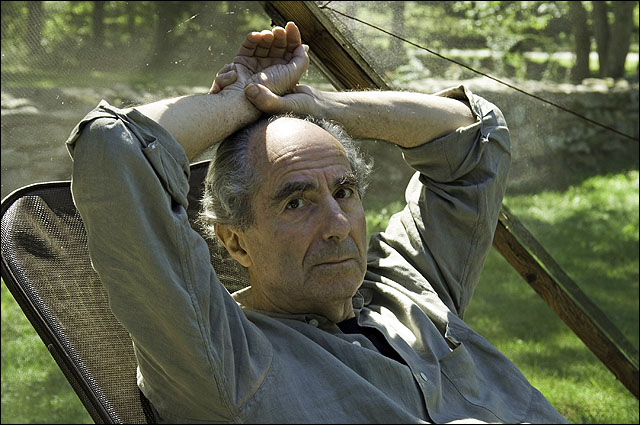

Novelist Philip Roth, 72, sits inside a screened tent at his home in Warren, Conn. Roth's complete works will be published by the Library of America, with the first two volumes out this fall.

Now, with Roth a lively 72, tall and straight-backed with dark, daring eyes, his work has been slipped inside shiny black jackets, stacked on shelves along with the works of Bellow, Mark Twain and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

“It’s an admission of the books into perpetuity,” Roth says.

Roth was born in 1933 in Newark, N.J., a time and place he has remembered lovingly in “The Facts,” “American Pastoral” and other works. The son of an insurance salesman, Roth has described his childhood as “intensely secure and protected.” He was, he later wrote, a “good, responsible boy,” but also “strong-minded and independent.”

His debut book, published in 1959, was “Goodbye, Columbus,” a novella and five short stories. It brought the writer a National Book Award and some extra-literary criticism.

The title piece was a love (and lust) story about a working-class Jew and the wealthy girl he romances. The aunt of the main character, Neil Klugman, is a meddling worrywart, and the affluent relatives of Neil’s girlfriend are satirized as shallow materialists. Some Jews saw Roth as a traitor, subjecting his brethren to ridicule before the gentile world.

“It seemed pretty reckless and vicious,” Roth says, adding that the book was also praised by such Jewish authors and critics as Bellow, Irving Howe and Alfred Kazin. “I was just trying to depict the way it was, the way it sounded, what they talked about. This was just what I observed or imagined.”

Roth calls his early books “apprentice” works and likens the process to a shoemaker learning his craft. The terse, but humorous “Goodbye, Columbus” was followed by “Letting Go,” a long novel about marriage and academic life. Five years later, in 1967, he released the most uncharacteristic work of his career, “When She Was Good,” an earnest story set in the Midwest. In 1969 came “Portnoy’s Complaint.”

The novel satirized the dull expectations laid upon “nice Jewish boys” and immortalized the most ribald manifestations of sexual obsession, forever changing the way readers thought of liver and cored apples.

He is less controversial now, perhaps less famous. But over the past decade, he has been honored with the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. Last year’s “The Plot Against America” was his most popular novel in a long time, and its story, the anti-Semitic presidency of Charles Lindbergh, was proof that his imagination was active as ever.