Chess 24/7 at 10th & Mass

Game helps former inmates

Sly and Willie will play you whenever you want.

Seven in the morning? Fine. 2 a.m.? Good enough.

Chess is the world to them. They’ve been on the corner of 10th and Massachusetts streets for three months, playing every day.

Sly taught Willie chess in rehab. They worked on their game together at Lansing State Penitentiary.

Their friendship and the game helped them get by then. Now, on the streets of the town where they grew up, it’s helping again.

“Move!” screams Sherman Talbert, whom everyone calls Sly. He slams down his knight and looks across the board. “Move!”

Sly plays the game hard and fast, just as he’s lived, daring his opponent — in this case, a young man in jeans and a white T-shirt — to stop him.

“Chess is life,” Sly says. “That’s what Bobby Fisher taught me.”

When he’s not playing chess, Sly reads about chess master Bobby Fisher.

Sly was arrested in 1986, after a shooting on Memorial Day in Centennial Park, the same place he met Willie more than 20 years earlier.

He did almost 10 years of a 5- to 15-year sentence for aiding and abetting manslaughter in the death of Russel Gensler. Prison is where he learned chess.

“Nobody gave me any respect,” he says of his first games. “I could never play with the good players.”

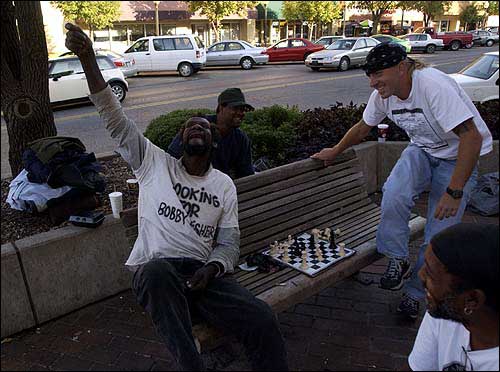

Willie Moore celebrates his win over Mike Gabb, of Lawrence, as Jeffery Clark, top, and Sherman Sly Talbert, bottom right, watch at the southwest corner of 10th and Massachusetts streets. Willie and Sly honed their chess skills while serving time together at Lansing State Prison.

But before long, he was unbeatable. He was a brutal player, he says. That’s the only way to get respect, to win the things you need in prison.

After he got out, he tried the straight life. But it wasn’t long before he was back in rehab, then in Lansing on drug charges.

That’s when Willie Moore came back into his life.

Chess therapy

Willie’s hands are enormous, crumpled and crooked, worn from arthritis and circulation problems. His body bears the marks of years in and out of prison and on the street.

But life changed for Willie when he went back to Lansing in the mid-1990s. His medical problems were at their worst. He couldn’t walk across the gray television room of the prison’s commons without stopping to rest.

“I couldn’t stand seeing him like that,” Sly says.

So Sly took Willie under wing. When Willie needed something — a sandwich, a bag of chips, a cigarette — Sly would bring it.

Lawrence Police officers give Sherman Sly Talbert a warning about blocking the sidewalk with chess boards. Players now must confine their games to a bench at the corner of 10th and Massachusetts streets.

In return, Willie did what he could. He held the good spot in front of the TV while Sly gathered what Willie wanted. He played game after game of chess with him. Sly tried to teach Willie to play aggressively, to always look for the kill.

But “I make a mistake, every time,” Willie says. “Especially when it comes to killing time.”

Sly says Willie can never become as good as he is because Willie’s I.Q. is 70.

Back to the streets

Sometimes, Sly says, the streets can be a dangerous place. Breaking up fights and dealing with drugs have become a daily chore for him.

“Twenty-two hours a day, it’s fine around here. The other two, it’s chaotic,” he says.

Unlike Willie, Sly had a place to go, away from the streets. Until three months ago he worked for Rhino Linings of Lawrence, living with a sister.

But once summer hit, he only wanted two things: To be with Willie and play chess.

“I wasn’t happy,” he says of living with his sister. “It felt like I was still in prison.”

He’s been sleeping on the streets with Willie ever since. But now, the temperature plummets at night. It’s hard for the two to play and sleep once the sun goes down.

And two weeks ago, the Lawrence Police Department served Sly a summons, telling him that playing chess on the sidewalk was in violation of city code.

Sly says that so far, the police have been kind, simply asking them to move back toward the bench on the corner. But he’s afraid that eventually, the games will be over.

There’s a cold wind, so Sly slides into a nearby bar to warm up.

“Willie drinks, that’s his big problem,” Sly says.

With Willie’s poor health, he won’t make it if he doesn’t take care of himself, Sly says. But Sly has a drinking problem, too.

“I’m trying, I’m trying,” he says.

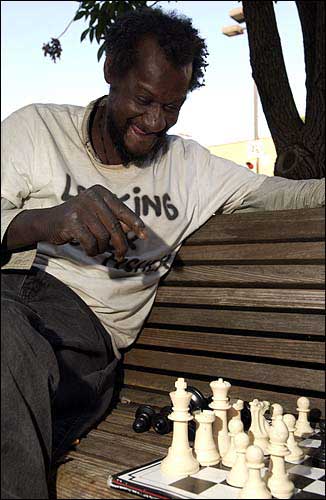

Willie Moore ponders his next move while playing chess at 10th and Massachusetts streets. The group of chess players has been ordered by the Lawrence Police to quit playing games on the ground, limiting the number of games the group can play at once.

Survival issues

Chess has helped Sly survive prison and a cocaine addiction, but it can’t keep him away from alcohol so long as he’s on the streets with Willie.

“I have a life, a home,” he says. “But how can I leave him?

“Chess is better than selling crack,” he says. “It’s better than stealing, than pimping. It’s better than doing prostitution. It’s all we have.”

Within a few weeks, Sly is hoping, he and Willie won’t be on the streets anymore.

Sly recently took Willie to Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services to pick up housing and disability forms.

Sly had to buy a pair of glasses so he could fill out Willie’s forms. Willie can’t read or write.

But SRS isn’t a sure thing. Meanwhile, Sly is looking for other options.

“I just wish I had something,” Sly says. “A van or a car. Something that Willie could sleep in at night.”

Sly gets frustrated and walks off. Willie flashes a toothless smile.

“He’s my best friend,” Willie says. “I love him to death.”