Tuskegee Airmen celebrate 60th anniversary of training

CHARLESTON, S.C. ? In the era of Jim Crow — when the Army brass didn’t think blacks were capable of flying — a group of minority pilots changed the way the military looked at race.

The Tuskegee Airmen, their ranks thinning as the World War II fighter pilots age, reunited Friday for a breakfast in Columbia, the first of several gatherings planned for the weekend.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the creation in 1944 of the advanced combat training program for the black airmen at a small Army Air Force base in Walterboro, S.C.

The program had started three years earlier in Tuskegee, Ala. In all, almost 1,000 pilots would be trained, 450 deployed overseas and 150 would lose their lives in training or combat.

The pilots deployed to North Africa and Europe flew support missions including strafing enemy ammunition dumps, rail lines and highways. Later, the airmen flew escort for bombers.

Including ground support personnel, there were about 14,000 Tuskegee Airmen, said 85-year-old Hiram E. Little Sr., a retired school teacher from Atlanta.

To the military, the program at first was simply “an experiment to prove the Negro could not fly and fight,” said Herbert Carter, of Tuskegee, who went on to a 25-year career in the military.

“We were just determined that all we wanted was an opportunity,” he says.

But even after the pilots of the first squadron were trained, the Army delayed deploying the unit for months.

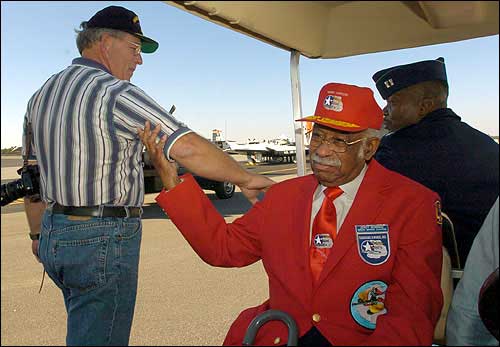

Karl Miller, left, of Manning, S.C., thanks Tuskegee Airman Leroy Bowman for his service to the United States, at the Celebrate Freedom Air & Ground Show at Woodward Airport in Camden, S.C. This year marks the 60th anniversary of the creation of the Tuskegee Airmen, an advanced combat training program for the black airmen at a small Army Air Force base in Walterboro, S.C.

“No commander from Burma to England wanted this all-black squadron,” said Carter, 85. “They said it would create problems. They were firmly convinced no white personnel would take orders from black officers. The Negro press and other organizations and sympathizers brought pressure on the War Department to do something about this unit.”

The airmen then proved they could handle anything asked of them.

None of the bombers escorted by Tuskegee Airmen fighters were lost during World War II, although 66 of the fighter pilots lost their lives and 33 other fighter pilots were shot down and taken prisoner, Carter said.

At war’s end, the airmen returned to a nation where little had changed.

“We were not so naive as to think America was going to change that much,” he said. “When we returned after V-E Day, things were as biased and racist as they were before World War II.”

It wasn’t until the late 1970s that the airmen began to receive recognition for what they had done.