A sansei story

Despite pending retirement, third-generation Japanese-American who built art career around identity has more teaching to do

Roger Shimomura was 6 or 7 years old when his family drove 200 miles from Seattle to Cannon Beach, Ore., only to be turned away by a resort owner who refused to rent to Japanese people.

They’d made reservations weeks in advance and had been looking forward to a relaxing vacation at a cabin by the sea.

Shimomura remembers his parents talking in hushed voices outside their 1946 Chevrolet about what to do.

Eventually the owner changed his mind and offered them the cabin furthest from the office. It hadn’t been used in years and was a mess. The Shimomuras drove to the nearest grocery store, bought armloads of cleaning supplies and spent the rest of the day scrubbing. The cabin gleamed when they were done.

After two days, they tidied up and returned to Seattle.

That was nearly 60 years ago. But time hasn’t washed Shimomura’s first brush with racism from his memory.

And these days, the third-generation Japanese-American (or sansei) doesn’t keep quiet about such injustices.

Shimomura, a painter, performance artist and distinguished professor of art at Kansas University, has gained an international reputation with paintings that are beautiful in a deceptive sort of way. With a look influenced by American comic books and Japanese woodblock prints, Shimomura’s works lure you in with gumball colors, crisp lines, flat tones and often-recognizable imagery of Americana and traditional Japan. Then they slap you when you realize what you’re looking at: blunt interpretations of racism, documentations of life inside Japanese internment camps, subtle political statements about identity.

The desired result is not necessarily shame but enlightenment, says Shimomura, who next week will retire from teaching after 35 years at KU.

Artist Roger Shimomura is set to retire next week after 35 years of teaching at Kansas University.

“Raising the sensitivity level and the awareness level — if you can do that, you’ve done something. It’s not meant to be any kind of manual for understanding all those things because, first of all, I’m not claiming to be an expert. Number two: I’m not claiming to understand what all the issues are that should be included by any means,” he says.

“But what I AM interested in doing is saying, ‘Hey, there’s something here that we all need to pay attention to and be sensitive to,’ just so that maybe you’ll stop and think before you say that next stupid thing.”

Ironically, it took a Kansas farmer who uttered just such a stupid thing to focus Shimomura on creating the kind of identity-driven art that has become his hallmark.

‘Gee-shee girls and kimonahs’

Shimomura attended an auction outside Lawrence in 1972. He’d been standing next to a farmer for a long time and, during a break in the bidding, the farmer addressed him.

“Excuse me, but I’ve been overhearing you speak the language and I was wondering how you came to speak it so well. Where are you from?” he inquired.

“Seattle,” Shimomura said.

“That’s not what I mean. Where are your parents from?” the farmer countered.

“Well, my mother was born in Idaho, and my father was born in Seattle,” Shimomura said. Of course he knew what the farmer was after.

Finally, the farmer said, “Are you Indian?”

“No. I’m Japanese-American,” Shimomura replied. “I teach at KU.”

Roger Shimomura visits with gallery-goers during the opening of his exhibition, Stereotypes

That did it. The farmer broke into some kind of World War II, GI slang and explained that he and “the little lady” collected pictures of “them gee-shee girls wearing them kimonahs.”

“Do you do pictures like that?” he asked Shimomura.

Exasperated, Shimomura said, “Yes,” and left it at that.

On the way home, he found a book at the Kansas Union based on Japanese woodblock prints. He combined a slew of iconic Japanese images into one painting and called it, sarcastically, “Oriental Masterpiece.”

When he showed the work in Seattle with six other paintings, it garnered all the attention. Essentially what people said, Shimomura recalls, was, “It’s good to see you doing work that looks like you.”

“And I really felt as I was doing this painting that I was working with something that was quite foreign because I had never had these kinds of things with me when I grew up,” he says.

Fascinated by the reaction, however, Shimomura spun the first painting into a series of 45 or 50 “Oriental Masterpieces.”

History revealed

Shimomura, 64, was born in Seattle in 1939. His family’s world was upended on Feb. 19, 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in retaliation for the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor three months earlier. The Shimomuras joined more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans forced to give up most of their worldly possessions and move to internment camps scattered across the West.

Shimomura, who was 2 at the time, spent the next two years with his parents and grandparents behind a barbed wire fence at Camp Minidoka in Idaho.

“There are very, very few things that my parents ever talked about regarding the camps,” Shimomura says. “For 40 years, they kept me totally in the dark. They said nothing.”

A party to celebrate artist Roger Shimomura’s 35-year contribution to Kansas University will be at 8 p.m. May 14 at Liberty Hall, 642 Mass. The event — which will feature cake and champagne, six live performances by former students, and a DJ — is free and open to the public. There will be a cash bar.

The next day, Shimomura will have a retirement dinner at his home, 1424 Wagon Wheel Road. A donation of $1,000 to the newly formed Shimomura Faculty Research Fund gets the donor and a guest into the dinner, a black and white lithograph by Shimomura and their name on a plaque in KU’s Art and Design Building.

Reservations for the dinner must be received by noon Monday and can be made by calling Shimomura at 842-8166 or Judy McCrea at 864-2952.

All contributions are welcome. Make checks payable to KUEA, Shimomura Faculty Research Fund, Kansas University Endowment, attn: Anne E. Johnson, P.O. Box 928, Lawrence 66044.

The fund has been established with an initial gift of $25,000 from Shimomura. It’s the first fund dedicated to faculty research development in studio art at KU.

But the reparations movement got under way about the time Shimomura obtained 56 years worth of diaries kept by his grandmother, Toku Shimomura, and his parents finally started answering his questions.

Shimomura based several series of paintings on the ordeal both as he remembers it and the way his grandmother recorded it.

Warhol and white lies

Shimomura developed his artistic sensibilities during the 1960s, when West Coast funk artists like Robert Arneson were giving the finger to tradition with their irreverent artworks. After a year of military service in Korea and a few unhappy years as a commercial designer, Shimomura swapped coasts and walked straight into the pop art movement at Syracuse University.

He fell under the spell of Andy Warhol. He made silkscreens of repeated images on canvas. He even did a multimedia presentation as part of his graduate work in which he fabricated an interview with Warhol, lied about having discovered a film by Warhol at a New York library and made up a bunch of other facts. It turned out to be his earliest stab at performance art.

“I found that in some ways it really didn’t matter whether it was the truth or not,” Shimomura says. “The fact was that everyone really enjoyed the performance, so that gave a certain amount of credence to the performance in my eyes, and I think that sort of got me thinking about it later on.”

The intricately choreographed fib must have impressed someone at Kansas University because when Shimomura graduated in 1969, he had a job waiting in Lawrence.

Early years

He didn’t plan on staying long, but the political energy on campus redeemed Shimomura’s preconceived notions of Lawrence.

“I remember being overcome with that sense as I stood across the street from the Union, watching it in flames,” he recalls of the 1970 Kansas Union blaze. “And I have to say that there was a certain kind of rush of excitement then that this was going to be far more interesting than I’d anticipated.”

The chaotic spirit of the era infected Shimomura and the five other young faculty members who joined the art department in 1969.

Jerry Lubensky, KU art professor, remembers a class project in which Shimomura, ever the prankster, assigned students to carve pumpkins and deliver them to the chancellor’s office.

Roger Shimomura jokes with students before his performance art class last fall at Kansas University. Shimomura is known for his dry sense of humor, but he also has a reputation as a brutally honest, though respected, teacher who has reduced students to tears.

And something about a happening — “kids running around naked and people wrapped in tape” — in the auditorium of Strong Hall, where the art department was housed in those days. The administration was there then, too. Peter Thompson, art department chair at the time, got a call at home that Saturday morning from an alarmed administrator.

“And all the young faculty were involved in this,” Lubensky says.

Tough guy

Shimomura’s known among students for his biting honesty. Some of them have horror stories of brutal critiques that reduced them to tears. Yet they respect Shimomura’s opinion.

“He is tough, forthright and has no inhibition whatsoever to smear your weaknesses in your face while others cringe,” says Mark Florance, a graphic artist who graduated from KU in May 2001. Shimomura chaired his thesis committee.

“He did not scare me or intimidate me because I knew he was someone who had something valuable to offer me. He almost always hit the nail on the head when he cut down what or how I was approaching my art.”

Shimomura’s influence has proven to be long-lasting.

Roger Shimomura adds color to a new painting that incorporates Dr. Suess characters into a collage of figures conforming to racial stereotypes of Asian-Americans. He worked at his home studio last week.

“Roger’s ghost is in my studio every time I work — coaxing me to be honest, to find my core, to do the work that is MINE,” says Marvel Maring, the fine arts librarian at the University of Nebraska-Omaha who met Shimomura in 1980 as a freshman art student at KU.

Shimomura started KU’s performance art program in 1985, the same year he began experimenting with the form himself. His course has become part of a new area of study at KU called expanded media, which also includes classes on installation art, mixed media and computer and book arts.

Through the years, as Shimomura’s art career has taken off, his commitment to students hasn’t faltered, they say, despite the fact that he’s often away from the classroom.

“In three years of meetings during my MFA work, Roger Shimomura never canceled or rescheduled a meeting. He really has the student’s welfare as a top priority,” says Julie Green, assistant professor of art at Oregon State University.

“Between 1996 and 2000, I requested 100 letters of recommendation for various teaching positions. Roger kindly provided all of those letters. Furthermore, he sent the letters off the same day he received the request.”

A magnetic enigma

Punctuality is, indeed, one of Shimomura’s trademarks. He’s organized, efficient.

Roger Shimomura works in his home office, which is packed with books, binders full of slides of his artwork, family photographs and collectibles. Shimomura spends hours at his computer and can often be found surfing eBay, a Web site that feeds his former auction-going habit.

He keeps his home office orderly. At his fingertips are three-ring binders full of slides of his work organized by series. Above those are binder spines labeled with yellow paper signs: “Jap Hunting Licenses,” “Patriotics,” “Racist Memorabilia” — sullen collections that fuel artwork.

Shimomura has a “soft, nostalgic, sentimental, romantic side that nobody sees,” says his wife, Janet Davidson-Hues.

But even Shimomura’s closest friends say he’s hard to know, that he’s something of an enigma. Yet he’s a magnet.

“I think that he assumes the role of the inscrutable Asian, that he likes to play that role. And I think he realizes that sometimes his presence is intimidating,” Lubensky says.

“If there’s anything that Roger is, he’s somebody that people tend to gravitate toward, even if he seems to be inscrutable. He has some kind of personality that people, even if they’re not attracted to it, they’re still attracted to it.”

Carol Holstead, a KU journalism professor who has known Shimomura for about five years, says, “I don’t think it’s easy to be Roger.”

“First of all, look at the muse that fuels his art. His focus is often his anger or his outrage at the way he and other Japanese-Americans are treated, his outrage at discrimination,” she says.

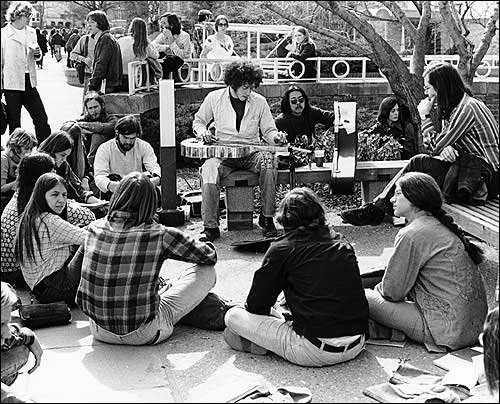

Roger Shimomura, the bespectacled man crouched to the right of the guitar player, hangs out with Kansas University students on campus. The photo was taken in 1970, one year after Shimomura joined the KU art faculty.

“You live with that muse. That, to me, wouldn’t be the happiest place to inhabit.”

More work to do

Undoubtably, anger and frustration drive much of Shimomura’s work

His most recent exhibition, “Stereotypes and Admonitions,” presents a startling spectrum of paintings based upon instances of racial insensitivity against him or other Asian-Americans. Many of the works cleverly impose on the “victims” the very stereotypes — yellow skin, buck teeth, demon qualities — that Shimomura wants to destroy.

A painting about the Cannon Beach incident is part of the series. So is “Passe,” a piece about an art historian who said Shimomura’s idea for a mural that explored whether America would be better thought of as a “melting pot” or a “tossed salad” was “sooo passe.”

Shimomura’s response to that criticism was the same as his reaction when New York Times art critic Holland Cotter wrote a 1999 essay about multiculturalism having worn out its welcome.

“What I do is not based on the kinds of ideas and principles that abstract expressionism or color-field painting or impressionism or any of the ‘isms’ in art were based upon,” Shimomura says.

“Being part of the ‘other’ is really what motivated me, ultimately, to do what I did. It had nothing to do with what I learned in art school about what was in, out or whatever.”

And those who would accuse Shimomura of thriving on the kind of racism that has, in a perverse way, made him a successful artist just don’t get it, he says.

“I genuinely understand the kind of pain that it causes. And I think when you start seeing your offspring have offspring, you wish anything that they do not have to experience what it feels like to be marginalized because of the way that you look,” he says.

“You just hope to God they don’t ever have to experience that. There’s nothing wonderful or cute or professionally rewarding or anything about that.”