How to build a ‘Monster’

Lawrence native Patty Jenkins turns her indie portrait of a serial killer into an Oscar front-runner

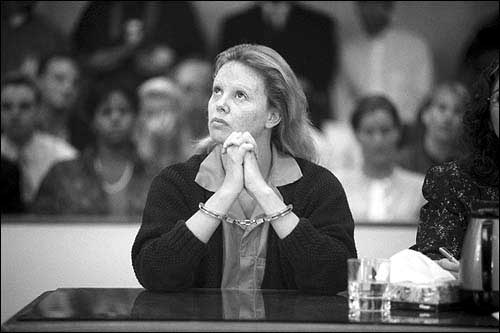

Charlize Theron portrays executed murderer Aileen Wuornos in writer-director Patty Jenkins' Monster.

Although Patty Jenkins never dreamed of becoming a filmmaker, the writer-director spent a good chunk of her youth seeing movies at the SUA theater on the Kansas University campus.

The obscure art-house flicks must have made quite an impression.

“When I got to be a teenager I would go out and smoke cigarettes … and go see ‘Hail Mary,’ that was banned everywhere else in the country,” says Jenkins, who lived in Lawrence from kindergarten through her junior year of high school. “So we saw everything. I think it was an incredible education.”

Now Jenkins’ “Monster” is earning far more buzz than “Hail Mary” ever did.

Her unflinching biopic — which opens today in Kansas City — has appeared on dozens of national top ten lists and proclaimed “the best film of the year” by über-critic Roger Ebert. Star Charlize Theron already has been nominated for a Golden Globe for her startling cinematic transformation into Aileen Wuornos, who was put to death in 2002 for murdering seven men in the late 1980s.

When the Academy Awards nominations are announced at the end of the month, most predict that Theron will be a front-runner for Best Actress.

“Charlize is so good that it overwhelms all conversation about the film,” Jenkins says.

“It never occurred to me that we could be nominated for an Oscar in any way before we made this movie. But I remember thinking when I walked away from the set, ‘If she’s not nominated, I don’t ever want to have anything to do with the Oscars.'”

There has been plenty of publicity about Theron’s physical metamorphosis from statuesque beauty to the mangy, stocky Wuornos. The South African ex-model gained 30 pounds, wore a prosthetic mouthpiece and had various applications on her face to simulate a weathered mottling. Yet, her outward appearance wasn’t nearly as jolting as Theron’s fearsome inner portrayal. She managed to humanize an individual who’d been dubbed “America’s first female serial killer” without excusing any of her behavior.

“It was almost entirely research; then the research dictated the transformation,” Jenkins explains. “We had one conversation at the very beginning of the process, which was not, ‘We’re going to do THESE things.’ It was about a certain thing we DON’T want to do. It was when these beautiful actors played these damaged women, that’s not what damaged people look like. Alcoholics don’t look gorgeous, with beautiful makeup on. People who are poor and living in poor communities, it takes a toll on that human being.”

Finding the real Aileen

As much, in retrospect, as an intimate look at the life of the notorious Wuornos would seem like something audiences and critics might respond to, the picture didn’t come together quite so easily.

“I was aiming very low,” Jenkins says. “I finally said, ‘I’ll just make a Roger Corman-style film. And there’s funding in these dumb serial killer movies, and I’ll make a character study out of it.’ It was almost an experiment. I thought, ‘Who knows if anybody will care to see her story this way? But the money is coming just because it’s a lesbian serial killer film.'”

One night when she was brainstorming on the project, she had an epiphany while watching “The Devil’s Advocate” on cable. The 1997 horror-thriller featured Theron in a supporting role, and Jenkins saw something deeper in the actress that went beyond her surface beauty.

“Charlize is who I wanted from day one when I started writing it,” she says.

Although the director auditioned nearly 50 people for the role, including Kate Winslet, Heather Graham, Kate Beckinsale and Minnie Driver, she eventually recruited her first choice. But not everybody was so inspired by her decision.

“I knew that when I cast Charlize, everyone thought it was a joke,” she recalls. “All the press we got was kind of bad, in so far as them saying, ‘Oh, this is a stunt-casting Oscar bid.'”

Adding to this pressure was Jenkins’ escalating correspondence with the real Wuornos, who’d been sitting on Florida’s death row for a decade.

“I became so engaged with Aileen and her story and so worried about dropping the ball on morally telling it correctly,” she confesses.

“Even my primary focus when I cast Charlize and Christina (Ricci) — of course I was excited that I got these stars. But instead of that being the paramount issue, it was much more, ‘Oh my God, I have to feel really confident that this person is going to live up to this,’ because I was answering to a person who had just been executed.”

Jenkins maintains the real Wuornos behaved very similarly to the way she was portrayed in the feature: alternately warm and hopeful but then capable of turning instantly mistrustful, fearing she would be taken advantage of by the filmmaker.

However, she eventually came to terms with how Jenkins would tell her story.

“The day before Aileen was executed — after Aileen and I had been writing letters to each other for quite some time — she gave her blessing to open up all her personal letters she wrote during the 12-year period spent on death row to Charlize and I,” she says.

Jenkins used these intimate details to craft a tale that was as much a love story between two women and a meditation on broken dreams as it was the examination of an infamous string of murders. In the wake of such recent flicks as “Dahmer” and “Ted Bundy,” it was key that Jenkins found a way to distance her work from the “dumb serial killer movies” genre that helped her to originally secure funding.

“Aileen gave me the opportunity to tell much more of an ‘In Cold Blood’ or ‘Badlands’-style story, because she was not a killer by nature,” she says. “It much more leant itself to, ‘How do you take a normal human being and make them into a killer?'”

And how will the families of Wuornos’ victims react to “Monster?”

“It’s a horribly difficult thing to say, but in all honesty I hope they don’t see the movie,” she responds. “But by not seeing the movie they’ll probably assume it’s a lot more sympathetic (to Aileen) than it is.”

Learning from Lawrence

Jenkins’ upbringing in Lawrence helped hone her love of film. Her first theatrical memory is seeing “A Little Romance” at the now defunct Cinema Twin Theatres (formerly at 31st and Iowa).

As she got older and became increasingly involved in the local hard-core music scene (which she says is the perfect setting for a screenplay she’d like to write some day), the former military brat claims the creative environment of the town exposed her to a lot of artists that she otherwise never would have met.

“While living in Lawrence, I hung out with William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, Marianne Faithfull,” she says. “Then the singer from Flock of Seagulls lived there. Jello Biafra was there for two years. Henry Rollins was there for a while. The amount of people I met and hung out with in Lawrence was beyond anything that I ever did until I lived in Hollywood. There were so many interesting people all the time.”

Aside from a general osmosis of Lawrence culture that helped inspire her, some specific memories from her past found their way into “Monster.” Critics have praised a romantic scene between Wuornos and her 18-year-old lover Selby (Ricci) set at a roller skating rink in the late 1980s. To the strains of Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin'” (the band’s singer Steve Perry actually assisted Jenkins as a musical consultant on the project), the pair share the film’s most hypnotically optimistic moment.

“I grew up skating at that old rink (Fantasyland) that was next to the Cinema Twin,” she says. “That was a hugely informative research point for me. It was important to me to think of something that I associated with romantic dreams of fitting in, and they did, too. I’d play that for everybody and say, ‘Just the way that you once wished you were that couple skating backwards to that Journey song, so did she.'”

That simple sequence became the highlight of the film for Jenkins.

“It’s the best thing I’ve ever written, and when I watch it, it’s the only scene that works every time for me,” she says.

After moving with her mother to Washington D.C. for her senior year of high school, Jenkins attended Cooper Union in New York City for her undergraduate degree. She subsequently headed for Los Angeles to attend the American Film Institute.

(“I live like two blocks from where the Oscar ceremony is held, and we joked when we moved here, ‘Oh great, we can walk.'”)

It was while screening her short film “Velocity Rules” at the AFI’s 2001 festival that she successfully pitched her idea for a Wuornos biopic to a producer.

Although “Monster” is now playing at Olathe’s AMC Studio 30 and the Tivoli in Kansas City, Mo., the movie is slated to open at Lawrence’s Liberty Hall within the next two or three weeks. Jenkins hopes to return to her hometown for the first time in six years to be host of the premiere.

“When I mentioned it to (the movie’s studio) Newmarket, they said, ‘You should go there,'” she says. “Lawrence had so much to do with my filmmaking in EVERY way. It would be an amazingly touching way to come back.”