‘Buffalo Commons’ idea gets second look

Population decline rekindles debate

Seventeen years ago, professors Frank and Deborah Popper touched off a firestorm by suggesting the farm-driven economies of the Great Plains were doomed and the region’s prairies should be given back to the buffalo.

Kansans ridiculed the Poppers’ ideas.

Then-Gov. Mike Hayden, who grew up near Atwood in Rawlins County, led the way. The Poppers’ suggestions, he said, “made about as much sense as suggesting we seal off our declining urban areas and preserve them as a museum of 20th century architecture.”

But in the days since Hayden was governor, Rawlins County has lost population — falling from 3,404 in 1990 to 2,966 in 2000.

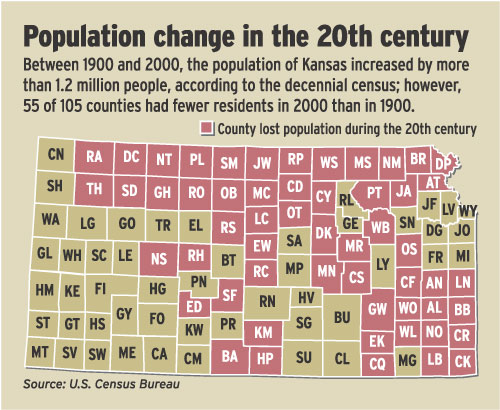

Rawlins County is not unique. Fifty Kansas counties lost population between 1990 and 2000; the losses in 12 of those counties exceeded 10 percent.

Ness and Comanche counties lost 17 percent and 15 percent, respectively.

Most of the 50 counties have been losing people for decades. Washington County, for example, had almost 22,000 people in 1900. Today, it has fewer than 6,500.

Small towns that once had bustling downtowns are lucky to still have a bank, a grocery store and a grain elevator.

Second listen

Buffalo graze on the tall grass of the Maxwell Wildlife Refuge near Canton. A proposal first made in the 1980s to turn large portions of the Kansas prairie back to the buffalo is being examined again as the state's population in rural areas declines.

Nowadays, Hayden says, the Poppers deserve a second listen.

“It’s true, I was one of their sharpest critics,” he said last week. “But I was wrong. Not only was I wrong — in many cases, the out-migration rates have exceeded what the Poppers predicted.”

On Wednesday, Hayden and the Poppers will be in Manhattan for “The Buffalo Commons Revisited: Conversations about the Future of the Great Plains,” a public forum sponsored by the Kansas Center for Rural Initiatives at Kansas State University.

“Back in 1987, the Poppers were considered radicals,” said Carol Gould, the forum’s coordinator and director at the Center for Rural Initiatives. “But a lot of their predictions, I’m afraid, have turned out to be more accurate than what we wanted to believe.”

The Poppers — he’s an urban studies professor at Rutgers University, she teaches geography at the College of Staten Island-City University of New York — say much of their initial message was lost in the translation between New Jersey and the Midwest.

Reality sinking in

“Early on, we were accused of being for some sort of forced, government-led land grab — that we were part of a big, federal land-grab camel that was trying to get its nose under the tent,” said Frank Popper. “I have no idea where that came from.”

The Poppers insist they have nothing against the Great Plains. And most of their adversaries’ tempers, they said, have cooled.

“Things tend to be calmer now,” said Frank Popper. “We haven’t had a difficult meeting in, gosh, it’s been years.”

The facts, he said, are sinking in.

“Modern agriculture needs fewer people, which means it’s getting harder and harder to keep people in the rural areas,” Frank Popper said. “There isn’t a substitute economy to keep them there.”

| “Buffalo Commons Revisited: Conversations about the Future of the Great Plains,” a panel discussion set for Wednesday in Manhattan, will feature professors Frank and Deborah Popper along with Mike Hayden, secretary of the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks.The forum, sponsored by the Kansas Center for Rural Initiatives, is from 2:30 p.m. to 4 p.m. at Kansas State University’s Forum Hall in the student union. The event is free and open to the public. |

And it’s clear, said Deborah Popper, that agriculture is depleting the region’s once-bountiful supply of groundwater and farmers are using ever-increasing amounts of pesticides and herbicides.

It’s no surprise, she said, that Kansas’ rivers are considered some of the nation’s most contaminated.

What’s Plan B?

“What we’re saying is that when the Plan A Economy — that is, agriculture — fails, there needs to be a Plan B Economy,” she said. “And to get to Plan B, there needs to be an ecological re-evaluation. Instead of the Great Plains being seen as a place that’s tied to an economy that no longer works, it should be restored to a place that’s both valuable and beautiful.”

Back in 1987, the Poppers proposed restoring “large chunks” of the region’s tall- and short-grass prairies, creating a vast, fenceless Buffalo Commons.

“The small cities of the Plains,” they wrote, “will be urban outposts scattered across a frontier that would be much bigger than today’s, cement islands in the shortgrass sea of the Commons. It will be the world’s largest historic preservation project, the ultimate national park. Much of the Great Plains will become what America once was.”

Today, the Poppers say a Buffalo Commons is only one of many possibilities.

“A lot of very smart, wonderful people are working on ways to make this happen,” said Frank Popper, referring to an economy that would replace agriculture. “At this point, I don’t know what it is, but I suspect that a generation from now or in the next century, looking back, it will be obvious.”

Gary Chaput, ranch manager at the L.C.L. Buffalo Ranch in Clifton, spreads out range

Stemming the tide

In Rawlins County, officials hope to stem the tide of out-migration by giving away land.

“If you’ll build a house in Atwood, we’ll give you the home site,” said Arlene Bliss, Rawlins County’s director of economic development. “And it’s not just in Atwood, it’s in McDonald and Herndon, too.”

Bliss said she’s had several inquiries, but no takers.

“I think it’s just a matter of time,” she said. “If you live in Denver and you’re getting ready to retire, you can sell your house there for $350,000, build a very nice home here for $125,000 and pocket the difference.”

The cities of Marquette, Minneapolis and Ellsworth, too, are offering free home sites. Washington soon will.

“We’re getting ready to,” said Washington’s 33-year-old mayor, Travis Kier. “We’re not in a position not to — we’ve got to do everything we can do to entice business and bring people to town.”

Washington, population 1,234, is hurting. It lost 57 residents between 1990 and 2000, and its population is one of the state’s oldest.

Aging population

According to the 2000 census, 21 percent of Washington’s population is younger than 18; 27 percent is 65 or older. In Lawrence, by comparison, 21 percent of the population is under 18, but only 7.5 percent is over 65.

“What we’re dealing with here is every time a farmer goes out — retires or whatever — his land gets bought up by those around him,” Kier said. “So instead of a new family moving in, we’ve got fewer people farming more land.

“And then with fewer and fewer farms, and with the farm economy being in a serious depression for a good 15 to 20 years, there’s nothing for the young people to come back for,” he said. “And without young people coming back, your population just gets older and older.”

At the same time, Kier said, Washington’s businesses find themselves competing with Wal-Mart stores in nearby Marysville and Concordia and in Beatrice, Neb. — all less than an hour’s drive away.

“We’ve held on to our downtown, but nobody’s getting rich,” said Kier, who owns grocery stores in Washington, Mankato and Clay Center. “We’re just trading dollars; there’s no new money coming in.”

Efficient?

In the next few weeks, Emery Hart, superintendent at Nes Tre La Go school district in Utica, expects to drive to Topeka to testify before the Legislature on behalf of the state’s small schools.

“A bunch of us take turns going up there,” Hart said. “If we don’t go, we won’t be heard. And if we aren’t heard, who knows what’ll happen?”

When he goes, Hart knows someone will argue that while what’s happening in the state’s small towns is regrettable, it’s also tied to efficiency. And efficiency always wins.

Hart isn’t so sure.

“Let me explain to you this way,” Hart said. “I happen to live in Grinnell, and my wife and I belong to the Methodist Church there. Last week, we had a meeting because the furnace is going out and it’s going to take about $20,000 to replace it.

“Now, since that meeting, I’ve had several Catholics come up to me and say ‘What can I do to help?'” Hart said. “That’s the way it is in a small town — there’s a sense of togetherness you just don’t get in a big city.

“I can’t see how wiping all that out — whether it’s through (school) consolidation or Wal-Mart or whatever — is more efficient,” he said. “There’s got to be a point where we stop and say, ‘Hey, we’ve lost more than we gained.'”