Grassroots guru

Nationally acclaimed baseball expert loves life in Lawrence

An hour from the nearest major-league team wouldn’t appear the ideal environment for a baseball writer, but it suits Bill James perfectly.

Despite recently becoming senior baseball operations adviser to the Boston Red Sox, living and working in the Lawrence area since 1967 has helped James keep his writing unbiased.

That detachment, he said, helped in the 1980s while writing the “Baseball Abstracts” — in-depth looks at teams, players and trends that made him famous.

“What I always try to do is not to immerse myself in the team, including the Red Sox,” James said. “I try to see things in perspective. The physical space from the team is helpful in doing that.”

Three decades in the Lawrence area didn’t keep the 54-year-old writer from getting attached to the town, though.

“This is where I’ve always lived, and it works for me, and I feel more in touch with myself … here than I do anywhere else,” James said.

In Lawrence, James is a famous writer, yet just another resident. It also is a nice setting for him and his wife, Susan, to raise their children — daughter Rachel, 17, and sons Isaac, 15, and Reuben, 10.

Though James’ work has been featured in The New Yorker, Business Week and many other publications since he was hired by the Red Sox in 2002, he still can walk down Mass. Street without a second glance.

“I believe in trying to be as normal as I can,” James said. “I wouldn’t be comfortable in a place where people overreact to celebrity.”

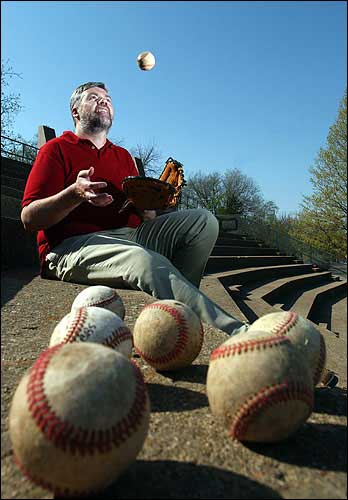

Lawrence resident Bill James, a nationally renowned baseball expert and senior baseball operations adviser to the Boston Red Sox, has kept his fame in a Midwest perspective. He feels comfortable living and working in Lawrence, where he can be both a famous writer and a normal family man.

ESPN.com senior writer Rob Neyer, who was James’ assistant for four years, said Lawrence was the perfect town for his former boss because it gave James freedom.

“The type of work Bill does really requires a lot of solitude,” Neyer said. “He has to be by himself just thinking of what he’s doing. He’s not writing reaction pieces to last night’s game; he’s trying to come up with original material.

“I think it’s probably easier to do that in Lawrence than in New York, where you have two baseball teams and God knows how many TV stations and magazines that want your time, and other writers who want to go out for a beer. I think that being in the Midwest is probably a good thing for Bill.”

Growing up

James was raised in Mayetta, a small town about 20 miles north of Topeka. A Kansas University fan, James remembers straining to hear on his parents’ radio KU’s triple-overtime men’s basketball loss to North Carolina for the 1957 NCAA championship. The game lasted so long, James went to school the next day with a stiff neck.

James graduated from high school in 1967, then moved to KU — an unlikely choice for a Mayetta High grad.

“To begin with, not that many of us went to college,” James said. “Those who did almost always went to Emporia State, and those who were ambitious went to K-State. I’m sure I was one of the first 10 people from Mayetta ever to come to KU, so it was pretty odd. But it just seemed more right to me.”

Majoring in English and economics, James started college in the fall of 1967 and lived in Stephenson Scholarship Hall for his four years on campus. He said he loved his time at Stephenson, though he didn’t necessarily have the same enthusiasm for his studies.

“It was just perfect for me. It gave me a group, which you need in college,” James said of Stephenson. “I wish I had been a more serious student. I wish I wasn’t infamous and didn’t have to talk about the fact that I wasn’t a serious student. Anyway, I wasn’t a very serious student or a terribly good student.”

One distraction — the major-league Kansas City Athletics — was taken away during his first semester at KU when A’s owner Charlie Finley moved the team to Oakland, Calif., at the end of the 1967 season. After the move, James couldn’t remain much of an A’s fan.

“It was pretty hard to root for Charlie Finley when he was right there in front of you,” James said of the owner known for adversarial actions toward A’s players and fans. “He was very off-putting. He had all the annoying habits of (current New York Yankees owner) George Steinbrenner, plus some.

“He had to remind you, about every 10 minutes, that this is his team and not your team. It was hard to root for him when he was right there and when he was halfway across the country it was really impossible.”

After the A’s left Kansas City, James developed a different mindset about baseball — which could explain his evolving methods of player evaluation.

“Whenever I studied anything, rather than applying it to whatever I was supposed to be applying it to, I would think, ‘Well, I can use this to study baseball,'” James said. “So I always wonder if that psychic separation from the game caused me to see the game differently during the time I was being educated. I don’t know. It’s just a theory.”

The writing

James’ works are renowned for objectively analyzing and predicting a player’s value. Of course, there was a time when those works were unlikely to exist.

After four years at KU and one course short of graduating, James joined the Army in 1971. He spent two years stationed in South Korea, during which time he wrote to KU about taking that final class. He was told he actually had met all his graduation requirements, so he returned to Lawrence in 1973 with degrees in English and economics.

“After two years of being in the Army, I just wanted to decompress for a while,” James said. “I came back to Lawrence and got an apartment and just stayed in bed for about a month to get over being in the Army.”

James then started working on an education degree, which he completed in 1975. While taking graduate-level psychology classes that summer, he had a meeting with professor Edward Wike that set him on a new career path.

Bill James' home office is loaded with boxes of statistics, magazines, rosters and other documents that help him conduct his daily sports research.

Wike told James, who always had wanted to be a writer, that the number of young people getting doctorates was far greater than the number of available jobs. Wike said James could work 10 years on his degree and have no guaranteed job.

“I thought, ‘You know, 10 years I could be a writer. What am I doing here?'” James said. “It just struck me. It was a gamble one way or the other, and if it’s a gamble one way or the other, you might as well do what you want to do. So then I went home and started writing articles.”

Starting out

His first article was a submitted piece for Baseball Digest about pitchers who had won 20 games and hit .300 in the same season, but it wasn’t long before he delved into more groundbreaking ideas.

His annual baseball abstracts in the 1980s gave a generation of fans a new way of looking at the sport. He named this new method sabermetrics — “the search for objective knowledge about baseball” — after the Society for American Baseball Research.

Rather than concentrating on a player’s intangibles, such as charisma and the number of winning teams he had played for, sabermetrics focused on what the player did on the field — such as getting on base or striking hitters out.

In 1985 James released his “Historical Baseball Abstract,” which became one of his most important and influential works. For decades, part of baseball’s appeal had been that, unlike other sports, there was no clock. Games moved at their own paces and seemingly could last forever.

In the “Abstract” James altered that viewpoint, espousing the theory that outs were the sport’s only finite component. With just 27 outs in a regulation nine-inning game, he proposed teams should minimize those outs wherever possible. A team shouldn’t purposely give one up with a sacrifice bunt just to gain one run early in a game, contrary to widely practiced strategy.

This theory popularized two statistics that have become synonymous with sabermetrics — on-base percentage (a player’s walks, hits, and hit-by-pitches divided by plate appearances) and slugging percentage (total bases divided by at-bats).

On-base percentage takes into account every a way a player reaches base without giving up one of his team’s all-important outs, and slugging percentage rewards extra-base hits. Each is a more informational measure of a hitter’s worth than the previous standard — batting average (hits divided by at-bats).

On-base percentage (OBP) and slugging percentage (SLG) are popular among fans and even baseball executives — namely Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane and Red Sox general manager Theo Epstein — making James even more famous. In fact, sabermetrics have become mainstream enough that Topps put OPS — the addition of OBP and SLG, a quick-and-dirty metric for determining a player’s value — on the back of its baseball cards for the first time this season.

This is home

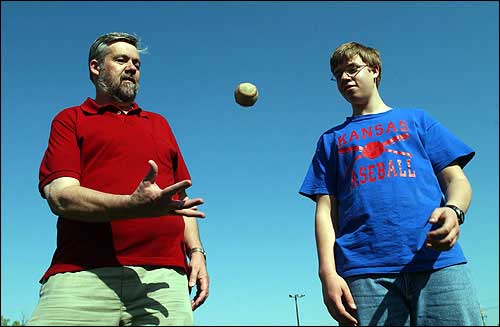

Bill James, left, and his son Isaac, 15, play catch at Hobbs Park. James and wife Susan have three children -- Rachel, 17, Isaac and Reuben, 10.

Even with increased fame and publicity, James has stayed in or near Lawrence. He moved to Winchester in 1982, but moved back to Lawrence in 1991 when his daughter Rachel was ready for kindergarten.

The small-town characteristics of Lawrence have kept James from more lionization.

“I can’t really pursue a television career in a meaningful way unless I leave Lawrence. I could do that, but television isn’t that natural to me anyway,” James said. “There are some things for which living in Lawrence is not ideal, but I’m a writer. I can live anywhere, and this works for me.”

He still makes an occasional TV appearance. James was a subject of Sunflower Broadband Channel 6’s River City Weekly in April 2001, and appeared on Dennis Miller’s show on CNBC earlier this month.

CNBC offered to pick James up in a limousine for the trip to and from the station in Kansas City, but James drove himself.

“You live in L.A., you live in that limo-type world. I couldn’t stand that,” James said. “You live in New York, you live in that intensely competitive environment in which where you rank compared to other writers is tremendously important. I couldn’t stand that.”

Even cities not usually considered entertainment meccas can take celebrity too far for James. While eating in a New Orleans restaurant once, he was taken aback by the fanfare before the arrival of Anne Rice, who lives in The Big Easy.

“New Orleans is a nice town, but I don’t want to live that way,” James said. “I love going to Boston. Boston’s fantastic. I love New York. It’s a great place to go. But this is home.”