Boy bands battle back for fans, respect

There are those who say the golden era of boy bands is over, swept away by a flood of lawsuits, solo ambitions and changing teen tastes.

“You’ll never see trading cards and cute boys in matchy-matchy outfits doing fancy choreography again,” says Zena Burns, music editor for Teen People. “It’s morphed into boys who play their own instruments in bands like Good Charlotte and Simple Plan.”

But if the boy band is extinct, somebody forgot to tell the boys.

“Penny & Me,” the first single from a forthcoming CD by ’90s sibling sensations Hanson, just debuted in the No. 2 position on the Billboard Hot 100. Former New Kids on the Block singer Jordan Knight has a new set of NKOTB material, including remixes of ’80s hits such as “Step by Step” and “Cover Girl.” And another New Kids alum, heartthrob Joey McIntyre, is set to release his album “8:09” on April 27.

The management of Menudo, the group that launched Ricky Martin, recently announced that it would audition 10- to 14-year-olds this summer in New York for a revival of the Latino boy band with the revolving-door policy. When a member got too tall, or his voice changed, or he turned 16 — whichever came first — he was summarily replaced.

After a four-year layoff and endless litigation, the Backstreet Boys are back in the studio. And despite the solo careers of J.C. Chasez and Justin Timberlake — and occasional film roles by Joey Fatone and space boy Lance Bass’ work on “Hollywood Squares” — the ‘N Sync guys say they’ll begin writing songs for a new CD this summer.

The hurdle all these groups face is that it’s exceedingly difficult for pop performers who had teen appeal to reconnect with their audiences.

“The typical Backstreet Boys fan was 12 years old in 2000. Now they’re 16,” notes Tom Vickers, a music consultant and former Capitol and Mercury Records executive. “Are they going to have the same reaction? ‘Oh, Brian (Littrell) is so cute!’ No. Now they’re into the Strokes or the White Stripes.”

Rudimentary formula

The hope, of course, is that maturing fans will see that their old faves have matured, too.

The Hansons will release their new disc, “Underneath,” April 20 on their own 3CG Records. “We played an acoustic show a few days ago, getting ready for the full tour this summer,” says lead singer and middle brother, Taylor, now 21, married, and the father of a 16-month-old son.

“It’s been four years since our last album and seven since our first one, and the fans are different than they were. … They’re in college and getting on with their lives. But they’re still singing along and waving their hands.”

The Henry Ford of boy bands is Lou Pearlman, a former air charter owner and cousin of Art Garfunkel. A remarkable fleet of groups — Backstreet Boys, ‘N Sync, LFO, Take 5, C Note, O-Town, Natural and others — have rolled off his Orlando, Fla., assembly line.

The formula is rudimentary, Pearlman says: “You need someone with dark hair, someone with light hair, someone with medium hair. You need at least three strong lead singers. And they have to be young and clean-cut, parent-friendly.”

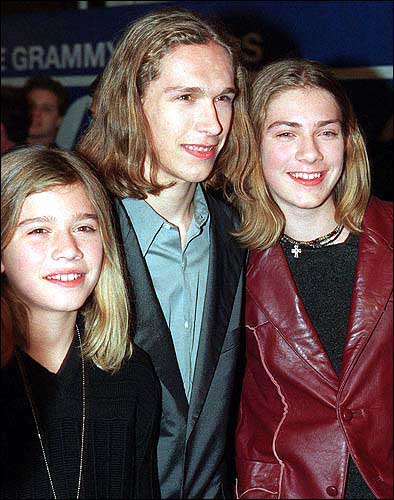

The brothers of Hanson, from left, Zac, Isaac and Taylor, are preparing to release a new CD. They're shown in a February 1998 photo.

On top of that, Burns adds, “you have the really cute one, the one who’s not so cute, the shy one, and the goofy one.”

If the makeup of these bands is predictable, so is their shelf life. “It’s a five-year run, on average,” Pearlman says. “The bands get to the point where they have a lot of money and they become more independent. Or else there’s a falling out and someone wants to go solo.”

All about the Benjamins

Eventually with boy bands, it seems money is a bone of contention. Backstreet Boys and ‘N Sync sued Pearlman, and members of O-Town, the band Pearlman created on the ABC reality series “Making the Band,” now say the contracts they signed were not in their best interest.

But even if they got ripped off, most former band members look back on their time with a degree of gratitude.

“The guy who created Menudo, Edgardo Diaz, promised us a lot of things that didn’t happen,” says Roy Rosello, who was in the Ricky Martin edition of Menudo in the group’s mid-’80s heyday. “All the money we were supposed to make we didn’t get, but the experience was worth it.”

“The business side was cutthroat, but I got to travel the world,” says Ryan Goodell, a former member of Take 5, a Pearlman group. “I loved going on stage and having girls holding up pictures of you.”

It took effort for the boys to keep their heads on straight: “A few minutes ago nobody cared, and now millions are screaming for you,” Taylor Hanson says. “To keep your sanity, you have to believe it’s not really you they’re screaming for.”

It was equally hard for some to re-enter civilian life. Goodell, 23, is an undergrad at UCLA and hopes one day to practice entertainment law.

“You get used to people catering to you,” he says. “Then suddenly I was just another application number to get into UCLA.”

Yes, things may be ugly in the shallow end of the pop music pool — the work is grueling, the chance of success slim, the management usually rapacious. But there’s never a lack of talented boys clamoring to dive in.

That’s why it may be premature to trumpet the end of the boy-band era.

“I’ll tell you exactly when it’ll be over,” Pearlman says. “When God stops making little girls. Until then, we’ll keep going.”