Firm feeds off straw potential

Lawrence's Pinnacle touts plastic product that's friendly to environment

Donna Johnson can drive along almost any rural road in Kansas these days and see tons of untapped potential.

She sees it in wheat straw, the part of the wheat plant left after the grain has been reaped.

Now, just days after the bulk of the state’s wheat harvest has been finished, there is field after field of the straw.

For eight years, Johnson, president of Lawrence-based Pinnacle Technology, has been working on a process to use all that wheat straw in manufacturing plastics. Later this month, the project will receive its biggest boost yet as a South African company will open the world’s first plastic production facility using Pinnacle’s technology.

The deal, Johnson believes, could easily double her company’s revenues and may mark the beginning in a change of how Kansas farmers view the state’s most abundant crop.

That’s because farmers now don’t think much about wheat straw, because there are not many uses for it. It is used primarily for for bedding for livestock or as mulch for garden plants and flowers. Usually, though, farmers have much more straw than they have use for, so they just burn it.

If Johnson has her way, the annual ritual of burning straw would become as uncommon as torching a pile of $20 bills.

“We’ve basically said our economic research shows that wheat straw would be worth $40 to $60 a ton if you delivered it to the gates of the factory,” Johnson said.

A typical wheat field produces about a ton of straw per acre, which means a farmer with a 100-acre wheat field could be looking at a check of from $4,000 to $6,000 for a byproduct he now views as trash.

“I’ve had farmers tell me, forget the straw, they’ll give me the wheat, too, at that price,” Johnson said.

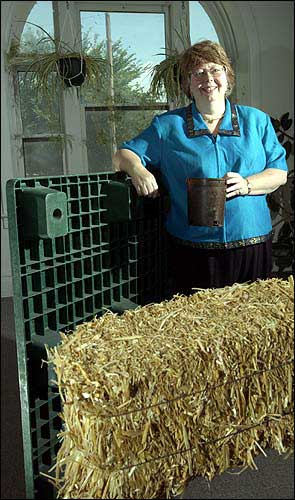

Donna Johnson's company, Pinnacle Technology, 619 E. Eighth St., has developed a means of making plastic using wheat straw. The first manufacturing facility for products made with the material will open later this month in South Africa. Johnson stands next to a shipping pallet and holds a plant pot, both made with 50 percent wheat straw like that visible in the foreground.

How it works

The $321 billion U.S. plastics industry produces many different types of plastics. Some are soft and flexible, while others are stiff and brittle.

The industry for years has been adding fillers, most often agents like calcium and talc, to make plastics that are stronger and more rigid.

Johnson, along with researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Products Laboratory, came up with the idea that wheat straw also could serve as a stiffening agent.

Now, about a decade later, Pinnacle, at 619 E. Eighth St., is able to show people everything from small planters to large shipping pallets made with plastics that are 50 percent wheat straw.

Tests have shown the product to be significantly stronger and stiffer than traditional plastics, but about 20 percent lighter than other plastics made with calcium and talc fillers.

That means wheat straw plastic could appeal to plenty of potential buyers.

For many manufacturers, the lighter weight would reduce shipping costs. The wheat straw plastic also is less abrasive on the companies’ expensive plastic molds, and is manufactured at a lower temperature than traditional plastics, which means plants could operate with lower energy costs.

The wheat straw plastic also requires less petroleum in the manufacturing process, a fact that could become a major selling point, depending on the future price of oil.

“The more expensive traditional plastics become, the more attractive this technology becomes,” Johnson said.

Matthew Naitove, chief editor of Plastics Technology magazine, said the wheat straw project hadn’t begun to receive much attention in the industry. But he said that could change if the company is able to show results from its South Africa project.

The idea of adding natural fibers, particularly wood flour, had received a lot of attention from the plastics industry, Naitove said.

“Natural substances are kind of the buzz in plastics right now because people are trying to be more green, more environmentally friendly,” he said. “I’d say they (Pinnacle) have tapped into an idea that is very hot right now. I think they’ll find a receptive audience.”

Poised for growth

The plastic won’t work for everything, though. For instance, it can’t be made into different colors, but it can be painted. Its natural color is a dirty brown. Neither can it have the high gloss look that is required for many plastic products.

Johnson said the company believes the best potential uses for the plastic are products that don’t have to be overly pretty. Specifically, the company has its sights set on the plastic shipping crate and pallet industry.

“If you think about it, that is a huge market, and we just need a little part of it to be successful,” Johnson said. “That is kind of our game.”

Pinnacle recently signed a licensing agreement with South African-based Spanish Ice Properties. Spanish Ice is the first to receive the rights to use the wheat straw technology. Its plant will produce plastic primarily for a crate and pallet manufacturer.

The plant is expected to be operational later this month and will produce from 150 to 200 tons of plastics per week. Pinnacle, and Agro-Plastics, the subsidiary Johnson created to manage the technology, will receive a royalty payment for every pound of wheat straw plastic sold.

Terms of the deal were not announced, but Johnson said it likely would represent a turning point for the company.

“We stand to do really well from this,” Johnson said. “It could easily double the size of the company as a starting point, and then as we let more licenses go, it could be much bigger than that.”

The privately-owned company doesn’t release its revenue figures. Johnson said the company would begin licensing the technology to other interested manufacturers in the next two to three months.

Johnson said company officials originally were projecting to license about 30 different firms, but now think the number could be higher because of strong international interest.

“Normally when we work on a project we keep looking for the deal killers, either political, or technical or economical deal killers,” Johnson said. “We usually find one along the way, but this is one technology that keeps looking better and better the further we go.”

Rural boost

The company, which has 15 employees, has received about $750,000 in grant money from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and various other federal agencies during the past eight years.

Johnson said the government had been interested in the project because of its potential to help rural economies. That potential is because of anticipation most of the factories that would produce the wheat-straw plastic would be in agricultural areas with an abundance of straw.

The South Africa plant, for instance, is in a town of 5,000 people “in the middle of a wheat field,” Johnson said. She said plants had to be in such locations because shipping straw over a long distance quickly makes the work economically unfeasible.

“Western Kansas ought to be excited about this,” Johnson said. “If you look at Kansas’ small towns, they are dying. It is hard to make money on the farm and kids are leaving home. This has definite potential to help rural areas.”

David Govert, a Kingman wheat farmer who helped found a cooperative of wheat farmers who would provide straw for a variety of projects, said he was excited about the potential jobs Pinnacle’s technology could bring to rural areas, but doubted it would change the economics of wheat farming in the foreseeable future.

That’s because he doubts whether the industry could get large enough to use a significant amount of straw. For example, he said, a plant like the South Africa facility that produces 200 tons of plastics a week, would only need 5,200 acres of wheat straw per year. That’s not much, he said, when you consider there are approximately 2 million acres of wheat just within 100 miles of Govert’s Kingman home.

But he said it was worthwhile for farmers to keep an eye of the future of straw. In addition to the plastics project, people also are working on ways to use straw for use in ethanol and to create a product called “straw board,” which could replace particle board.

“I think it is exciting that we have people doing these projects now,” Govert said. “We just need a lot of them.”