Wyoming museum as wild as the West

CODY, WYO. ? On many Fridays, the lunch conversation between Charles Preston and Bob Pickering drifted from their work as curators at a natural history museum in Denver to ways they’d liven up the joint if they were in charge.

There would be mood lighting and animal sounds. Smells bringing to mind fresh rain or forest fires. Do-touch exhibits helping draw visitors into the wild worlds of bears, birds and wolves. Oh, and games encouraging joyous outbursts from children!

Preston and Pickering got their druthers down to the giggling kids in the new Draper Museum of Natural History in this Yellowstone National Park gateway community.

“There’s no law that says you can’t have fun while learning and I think that’s the challenge, museums have faced in the past,” says Preston, the founding curator.

The challenge: striking a balance between the traditional formula of information overload in hush-hush settings and a more freewheeling approach to presenting facts that Preston likens to theme parks.

And, he admits, it wasn’t easy. The Draper, with its drama, also needed to meld in with the four other Western heritage museums sharing the seven acres of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center. The others are the Buffalo Bill Museum, the Whitney Gallery of Western Art, the Cody Firearms Museum and the Plains Indian Museum.

Technology does play a role in some of the other museums video and sound help tell the stories at the Plains Indian Museum, for example. But, largely, they follow a more traditional route of presenting history with glass cases surrounding antique guns and clothing and small signs explaining to visitors an exhibit’s significance or story.

The vision for the $17 million Draper, which Preston and others built from scratch, was presenting the West’s stories in a new and different way, expanding on what visitors were taking in at the other galleries.

New directions

A trailhead marks the start of the museum, which takes visitors to exhibits of arts and animals, the serious and the slightly silly. An example: a tiny cabin where parents often are seen on hands and knees alongside their children, examining latex versions of bear, deer, elk and moose scat.

“It was always my feeling that a museum should stimulate the senses,” Preston says. “Hopefully it’s sucking you into this environment. And when you feel a part of it, I think you develop an appreciation of it.”

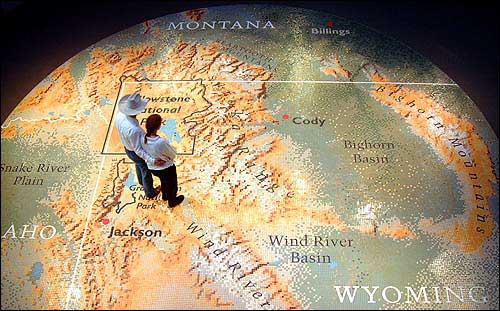

Visitors to the Draper Museum of Natural History in Cody, Wyo., stand on a round tile mosaic showing the greater Yellowstone region. The Draper Museum is widely regarded as one of the premier museums of the American West.

The faint smell of smoke and the crackling sound of kindling fill the air as Janice Waletzko, 54, walks closer to the orange glow and a cluster of televisions showing video of the 1988 wildfires at nearby Yellowstone.

Preston and Pickering consider the museum’s proximity to Yellowstone, about 50 miles to the west, an asset and advantage in telling stories and furthering understanding of the give-and-take between humans and nature.

The region showcases that relationship. Bears, for example, sometimes wander into yards. And this meeting of wild and tame, wilderness and pasture has made the region a lightning rod for controversy.

The museum takes it on. One exhibit, featuring two mounted wolves and sounds of their mournful calls, explains not only their lives but also the controversial reintroduction of the predator to Yellowstone. Solicited visitor comments fill a poster-board exhibit, responding to whether the move was positive. Answers range from “NO!” to “restore balance in nature.”

Wildfire management is another issue.

| Getting there: Cody is about 50 miles east of the eastern gate to Yellowstone National Park, a scenic drive marked by jutting buttes, stark canyons and frequent wildlife sightings.What’s there: Cody is well-known for its Western vibe, from the nightly rodeos that run throughout the summer to the specialty shops lining main street and restaurants offering Western dining. Nearby are Buffalo Bill State Park and the Shoshone National Forest, as well as Yellowstone.For more information:www.bbhc.org/ |

“We’re not here to advocate a specific position or tell you what to think,” Pickering says. “But there has to be some discussion for what it takes for a healthy environment. We believe it’s impossible in this day and age to separate the natural environment from the human culture that lives in it.”

Environmental lessons

Officials hope one day to use the Draper as a kind of “base camp,” preparing students or others for the environments and situations they could encounter in planned nature programs. They also envision seminars for scholars and lay people alike, expanding on the center’s current penchant for public forums on such issues as Western culture and history.

“The environment is part of the history of the West,” Pickering says. “You can’t understand the human stories unless you understand the environment: What drew generations of Indians to this land? Why did Buffalo Bill choose to build a town here instead of somewhere else?”

The historical center provides a cultural weight and another drawing card to the town named for the famed showman, a town well-known for its rodeos and theatrics of late-day gun duels.

“With the Buffalo Bill Historical Center and the Draper, there is enough to do in the area that you can stay a week and not repeat yourself,” says Gene Bryan, executive director of the Cody Country Chamber of Commerce.