Violence, racism marked era when police killed black teen

Stephen “Jerry” Dowdell can’t remember who called that night to let him know a Lawrence policeman had shot and killed his brother Rick.

But he remembers going to the alley between New Hampshire and Rhode Island streets, south of Ninth Street, where it happened.

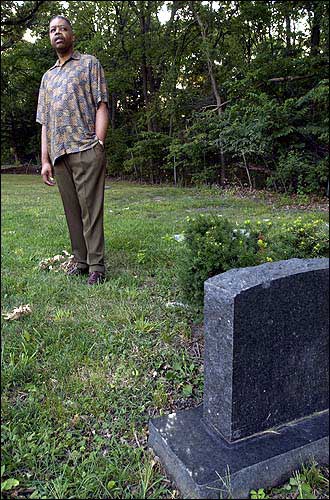

Stephen Dowdell visits the spot where his brother Rick Dowdell was killed by a Lawrence policeman on July 16, 1970. Rick Dowdell was shot by police in the alley, near Ninth and Rhode Island streets, that is behind what is now the Lawrence Arts Center.

“The pool of blood was still there,” he said. “Somebody said they’d taken the body to Lawrence Memorial (Hospital), and I said, ‘That’s where I’m going.'”

Accompanied by several friends all members of the militant Black Student Union Dowdell, then 22, marched into the emergency room.

“They didn’t want us in there,” he said. “The police were there, and some scuffles broke out. But I wasn’t going to let anybody keep me from seeing my brother. I got in.”

“They had him laid out on a table, and they’d covered him up with a sheet, but I pulled it off. He was there, his eyes were sort of half open, and there was a hole above his left eye, right about here,” Dowdell said, placing his index finger above his eyebrow, about an inch from his nose.

The hole, he said, was about the size of a 50-cent piece.

“I stood there staring, then crying, staring, then crying,” he said. “It was a horrible sight; it’s a vision that’s stayed with me all of my life.”

Though it was 32 years today, Dowdell, 54, has never before said much about that night.

Since becoming a born-again Christian and being named a deacon at Ninth Street Baptist Church, 847 Ohio, Dowdell said he had found the strength to let go of the anger he’d carried since that day.

“I want some closure on this,” he said. “I can’t forget what happened, but I can forgive. To forgive is the godly thing to do.”

When the shooting happened in July 1970, Lawrence was reeling. Protests against the Vietnam War were no longer peaceful; black students were arming themselves, and the Kansas Union had been set afire.

Ron Washington, chairman of the Black Students Union at Kansas University, left, addresses a strike rally on campus in this file photo from December 1970, as an unidentified youth displays a sign in memory of Rick Tiger Dowdell. Dowdell was fatally shot while fleeing police on July 16, 1970.

Everyone, it seemed, knew somebody who’d been shot or shot at.

It was in that atmosphere the chain of events leading to Dowdell’s death began.

About 10:15 p.m. July 16, Mildred Johnson, who was white, was shot in the leg while she and her husband were in the backyard of their home across the street from what was then St. Luke’s A.M.E. Church, 900 N.Y.

About that time, police heard two black men had been seen firing a handgun on the church’s front steps, and that the suspects were seen running toward Afro-House, a Black Student Union-run community center two blocks away at 946 R.I.

Minutes later, officers spotted two people a young man and young woman leave Afro-House in a red Volkswagen. After a short car chase, the Volkswagen stopped near Ninth Street and the alley between Rhode Island and New Hampshire streets.

Rick Dowdell reportedly got out of the Volkswagen and began running down the alley, apparently back toward Afro House. Officer William Garrett gave chase.

Seconds later, 19-year-old Rick Dowdell lay dead, shot once in the back of the head.

No eyewitness

A KBI investigation later found that Rick Dowdell’s .357-caliber magnum handgun had been fired once. Garrett fired four shots.

The officer said Rick Dowdell shot first. Though others heard the gunfire, there were no eyewitnesses.

After seeing his brother’s body, Dowdell drove to the police department, then at 745 Vt., the building that now houses Douglas County Senior Services.

Black and white youths gather for a rally in front of Strong Hall at Kansas University in this file photo from December 1970. Some participants carried posters of Rick Dowdell, who was killed that July.

“I got out and just started shooting, both guns I had a .357 magnum and a .38,” he said. “When I ran out of bullets, I threw rocks at the building. I was so angry.

“But nobody ever came out or shot back, so I left.”

Dowdell said that for several weeks after his brother’s death, he and other militants took shots at passing police cars.

“At the time, I didn’t care what happened,” he said. “But now, I thank God that I never hit anyone or killed anyone. I couldn’t live with that on my conscience.

“God was watching out for me.”

Dowdell wasn’t alone in his anger. The shooting death of his brother triggered a rash of firebombings and shootings across Lawrence, and it fueled a July 20 disturbance near Kansas University that ended in the random shooting death of Nick Rice, a white, 18-year-old freshman from Overland Park.

The next morning, Gov. Robert Docking put Lawrence under “a state of crisis and emergency,” banning the sale of ammunition and restricting gasoline sales to those involving motor vehicles.

Reaction to the deaths of Rice and Dowdell differed.

“Rice’s death generated much more sympathy and outrage from the community as a whole than did Dowdell’s,” said Rusty Monhollon, historian and author of “Is this America? The Sixties in Lawrence, Kansas.”

“Nick Rice was seen as sort of an innocent bystander. But there were some who saw Rick Dowdell as a bad seed. They figured if he was carrying a gun, he must have been looking to do something wrong or about to commit a crime.

The casket of Donald Rick Dowdell, 19, is carried from the St. Luke A.M.E. Church, 900 N.Y., in this July 23, 1970, file photo. Dowdell was fatally shot by police after a car chase. The front two pallbearers at left are Dowdell's brothers, Randy and Stephen Dowdell, and the fourth man back on the left side is Duane Vann, former president of the Kansas University Black Students Union.

“But to others, especially those in the black community, the fact that he was armed was an act of self-defense,” Monhollon said. “They sincerely believed the police were a threat to their safety.”

Stephen Dowdell said he almost always carried a gun in those days.

“It was very different back then,” he said. “We looked at the police as the enemy that was out to get us.”

Forced change

Rick “Tiger” Dowdell’s death forever changed Lawrence, forcing a then-quaint college town to confront the racism subtle and overt that had kept its black and white communities mostly separate and unequal for as long anyone could remember.

“What happened that night and for much of that summer served as a wake-up call,” Monhollon said. “People finally started to realize that they had some very serious problems on their hands but that a lot of these problems could be solved with some basic communication.”

In August of that year, the Lawrence Chamber of Commerce created a task force aimed at finding ways to improve relations between the police and the community. At the same time, the Lawrence City Commission brought in the Menninger Foundation to build bridges between the city’s communities.

Later that fall and winter, KU officials opened discussions with black student leaders, eventually agreeing to start the Department of African-American Studies and the Office of Minority Affairs.

“By itself, Rick Dowdell’s death did not change Lawrence,” said Jesse Milan, a KU graduate, the city’s first black schoolteacher and now president of the Kansas State Conference of Branches of the NAACP. He lives in Kansas City, Kan.

“Things were in place to make things happen before Rick Dowdell was killed, and they remained in place after he was killed. It’s not like we were dormant,” said Milan, 74. “But his death became an awakening factor awakening to the fact that nothing good ever comes out of violence. Violence only begets violence.”

Present shows improvement

Alice Fowler, who served eight years on the Lawrence school board, said race relations in Lawrence were better today than they were in 1970.

Stephen Dowdell visits his brother Rick Dowdell's grave in Oak Hill Cemetery. Rick Dowdell was fatally shot while fleeing police on July 16, 1970, while racial tensions were coming to a boil in Lawrence.

“It was crazy back then,” said Fowler, who is black. “People were scared, black and white. They were afraid to go out at night, afraid for the children. People were on top of buildings shooting. I remember hearing bullets hit the trains that ran by my house in north Lawrence.”

She remembers white-owned restaurants snubbing black customers, real estate agents seeing little reason to show black clients homes in all-white west Lawrence, and black graduates of Lawrence High School and KU not being able to find work in the city.

“Lawrence likes to be known for its history and being the Free State, but a free state it wasn’t,” she said.

Fowler said that while efforts to improve the city’s race relations turned a critical corner in the summer of 1970, there was still much to do.

“Strides have been made. There’s more diversity, but I’m afraid Lawrence is not as inclusive as it likes to think it is,” she said, noting there’s still tension between members of the city’s minority group and its police department.

Milan said that as president of the state’s NAACP chapters, he still hears complaints about Lawrence.

“It’s mostly police harassment, employment discrimination, benefits discrimination and housing discrimination,” he said. “Now, it’s true that progress has been made you see black clerks in the stores there, and a black person doesn’t have to sit in a certain section of the movie theater. But when you get into the broader economic issues that come with being able to get ahead, that’s where the differences remain.”

‘Still bothers me’

Gale Pinegar joined the Lawrence Police Department in 1967. He, too, remembers the night Rick Dowdell was shot.

“I’m the one who found Rick,” he said. “It was a very unfortunate thing to have happen. It shook a lot of us up. All of us were scared.”

Dowdell’s death, he said, was not a waste.

“I don’t how to put this into words, but after Rick was killed there was almost a sense of relief I don’t know if that’s the right word that, finally, people would realize the seriousness of the situation we had here. I mean, up to then people didn’t think something of this magnitude could happen in Lawrence.

“I say it was a relief, but it was unfortunate these things couldn’t have been worked out without somebody getting killed,” Pinegar said. “It still bothers me.”

Pinegar, 60, left the department in 1973. He’s now a car salesman at Laird Noller Automotive.

Now that forgiveness has brought him peace, Dowdell isn’t sure what to do next.

“I want people to know some of the things that went on in Lawrence back then, and why some of those things happened,” he said. “And then I’d like to reach out to youth to let them know that no matter how many mistakes you make, there’s God. You should stay close to God.

“The other thing is that I want to know in my heart that Rick did not die in vain.”