Big O says statistics ‘cheapened’

Assists easier to attain nowadays, Hall of Fame guard Robertson maintains

Basketball’s most glamorous statistic is the triple double, numerical evidence that for one game, a player dominated every phase of play scoring, rebounding and assists.

The first two categories are hard to argue with. The third one often comes with a wink.

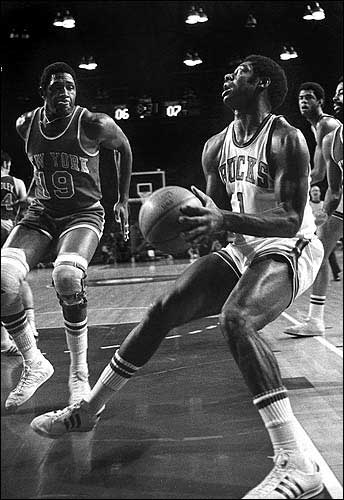

oscar robertson (1) drives to the basket against New York Knicks' Earl Monroe in this Nov. 23, 1973 file photo in Milwaukee.

There was a time when there were certain requirements for a simple pass to graduate to the exalted status of an assist. Now, the definition has been broadened a bit.

Oscar Robertson, who knows something about the subject, would suggest it’s been broadened a lot.

“The way assists are counted now, they’ve cheapened them,” Robertson said. “When I played, an assist had to be on a shot going to the basket, without a dribble. Not now.”

Forty years ago, Robertson averaged a triple double for the NBA season 30.8 points, 12.5 rebounds and 11.4 assists per game. It remains one of the most remarkable feats in basketball history, almost certain never to be duplicated.

“It was just a stat,” Robertson said. “Nobody made a big deal about it then.

“Now, with people watching so many games, it’s become a big deal.”

Jason Kidd led the NBA in triple doubles this season with eight. The whole league had 29. Compare that to Robertson’s 41 in 1961-62 a triple double every other game on the way to 181 for his career. The only other player with more than 100 was Magic Johnson, who had 138.

That’s how much better the Big O was than anybody else.

From Robertson’s point of view, his individual numbers were nothing more than that numbers. “All I wanted to do was play and win,” he said.

That was an exceedingly difficult task for the Cincinnati Royals until Robertson arrived in 1960. The team was struggling, out of the playoffs for three straight years, still burdened by the loss of Maurice Stokes, who was stricken by encephalitis in 1958.

Robertson became the centerpiece of its reconstruction.

“I didn’t understand the ins and outs of the pro game when I got there,” he said. “But I knew one thing. If you put good players together, it makes you win. You need manpower. Without good athletes, you don’t win. It was true then and it is true now.

“In the beginning, we were not a good team, at all.”

Slowly, that changed. Robertson joined holdover Jack Twyman. Jerry Lucas was added two years later, and was joined by Bob Boozer and Wayne Embry to give the team a frontcourt presence.

And always there was Robertson, wheeling and dealing, scoring, rebounding and dishing slick passes left and right. Night after night, he was running up triple doubles at a time when they didn’t have that distinctive name. He became the only guard to lead his team in rebounding and the only player to have over 900 assists and 900 rebounds in the same season.

Could this ever happen again?

“It would be tough to do it again,” Robertson said. “The key is rebounding. You can score 10, 11 points and get 10 assists, especially the way they count them now. But the rebounds are another matter.

“If you are a fundamentally sound player, you box out and rebound. When I got to the Royals, it was not a great team of rebounders so I went after it.

“I was trying to win games. That’s all I was trying to do.”

He succeeded. The Royals improved from 19 wins the year before he arrived to 33 in his rookie season to a peak of 55 by 1963-64. Then they gradually slid back.

It wasn’t until Robertson was traded to Milwaukee in 1970 that he won the NBA championship. Having Lew Alcindor, later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, on the receiving end of those passes helped Robertson and the Bucks win a title.

“Some teams never get there,” Robertson said. “You’ve got to get guys willing to play together and hope you get some players off the bench who can come through.”

Robertson played two more seasons with the Bucks and then retired.

He does work for the National Kidney Foundation and is a dedicated advocate for organ transplant. Five years ago next month, he donated a kidney to his daughter, Tia. Both are in good health today.

That, of course, was the biggest assist of Robertson’s life.