Ghosts of WWII

Tale of Lakota warrior passed on

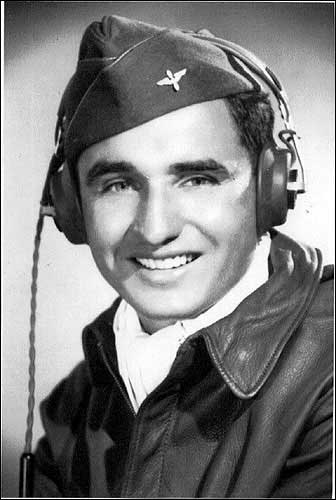

His Lakota Sioux name was Lone Ghost. But to family and friends, Homer Claymore was known as Smokey, because of his dancing gray eyes and dark skin.

His grandmother, Martha Claymore, seemed to know his fate when she first held him after he was born Nov. 17, 1918, less than a week after the Armistice, which ended World War I.

“Another soldier is born,” she said solemnly.

Years later, her daughter Emma Claymore Kesler, my grandmother, would remember those prophetic words.

Homer Claymore’s story — how he went from a South Dakota Indian reservation to Haskell Institute and then into the U.S. Army’s horse cavalry before becoming a decorated World War II B-17 pilot — has become a part of the Lakota oral tradition. Stories of his deeds are passed from one generation to the next, telling of the dark young man from Cheyenne River Reservation with the light-colored eyes.

‘Older than his years’

Grandmother Kesler, before she died in January 2003 at age 99, remembered her young nephew Smokey as a child who used to play around her house.

“He was so handsome, even as a young boy,” she recalled. “But he was different, too, much older than his years. He used to come up with the darnedest things. Sometimes I would just watch him and smile. He used to be playing out there and then he would always say, ‘The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.’ I never asked him why he said it or where it came from, but he said it a lot. It seemed strange for such a small boy to say that, but he did. It is funny that mother would have said, ‘Oh, another little soldier,’ and that we would lose him like we did.”

His maturity and kindness made his sister, Ina Claymore Palmer, idolize him as she was growing up.

And when she learned her brother had been killed in World War II, she was devastated. As she has grown older, the realization of what Homer Claymore could have become still haunts her.

Life-changing example

But his example would lead her to Lawrence, where she graduated from Kansas University’s nursing program and then joined the military as a nurse. Ina, who now lives in Mesa, Ariz., often returns to Lawrence to visit the place both she and her brother grew to think of as home.

Homer Claymore became the true embodiment of a Lakota warrior as the pilot of a B-17 bomber. Many compared him with Crazy Horse as he fought the air battle against the Germans. In 2002, he was inducted into the South Dakota Aviation Hall of Fame.

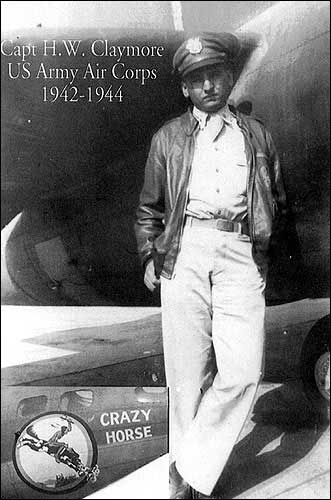

Capt. Homer Claymore, a Lakota Sioux and pilot during World War II, poses with his B-17 Flying Fortress, which he and his crew nicknamed Chief Crazy Horse. Claymore died in 1944 when his plane was shot down over Hamburg, Germany.

Homer was the son of George and Olive Williams-Claymore. After his father’s death, the family struggled to make a living. Homer and his brother Luther, both older than Ina, went away to a government boarding school in South Dakota. Olive and Ina first went to live with relatives. Later, Olive was able to get a job at the old Cheyenne River Indian Agency.

Time together for the family was precious, especially for young Ina, who only saw her brothers for short periods during Christmas holidays or during the summer.

Coming to Haskell

Homer moved to Lawrence to attend what then was called Haskell Institute when he was old enough for high school. Cooking became a favorite pastime, and after graduation he stayed on at Haskell’s vocational school and took up the baking trade.

Ina’s memories are those of a little girl who loved it when her brother came home for a visit from Lawrence and fixed macaroni and cheese.

By the spring of 1942, Homer was drafted into the U.S. Army. The cavalry hadn’t yet been phased out, and Homer soon found himself back in South Dakota training at Fort Meade, once a large cavalry base.

A part of the past of the Lakota people was about to play itself out again: The horses were going to be taken away. Ina said Homer remembered the stories of what had happened to his people after that happened. He did not want to find himself put aside and forgotten as his ancestors had been. He was somehow going to be a warrior.

His chance came when he was offered a choice: Become a baker or join the U.S. Army Air Corps. For the young man who had excelled at math and science, the choice was simple. Soon his pilot training began.

Capt. Homer Claymore

Off to war

After earning his commission, Homer was assigned to the 305th Bomb Group and was the flight leader of the 366th Bombardment Squadron. He flew 35 combat missions over Germany. He and his crew, flying a B-17 Flying Fortress nicknamed Chief Crazy Horse, were among the first bombers to lead raids over Berlin.

Capt. Homer Claymore lost his first Chief Crazy Horse when the plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire. He was wounded in the arm but managed to get the crippled plane back to the base in Chelveston, England. With his crew intact, Homer chafed at his inactivity and couldn’t wait to get back into the air.

According to letters he wrote to the family, he had done the nose art on the first Crazy Horse and soon began painting his second plane, named Chief Crazy Horse II.

Letters from home were a comfort. Olive Claymore wrote to her son every day, sending him care packages when she could. And he wrote back. His last letter was to a younger cousin about to graduate from high school.

Ina still has many of his letters, copies of which she has given me.

The final chapter

June 18, 1944, while flying a mission over Hamburg, Germany, his plane was shot down. Only the bombardier, who spent the next year in a German prison camp, survived. We never learned his name. But the fate of Homer Claymore and the rest of his crew remained a mystery the next two years.

“My mother was told that Homer was missing in action,” Ina remembered sadly. “But we didn’t know anything until 1946 when they finally told us he had been killed.”

Homer had been buried in a mass grave in Europe in a location still unknown to the family. His body and those of his crew were eventually returned many years later and buried near St. Louis.

Now, little more than stories and memories are left of the young warrior who was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart, the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

With the passing of his Aunt Emma Kesler, the last of the generation that heard Martha Claymore’s words about Homer shortly after his birth and watched him play as a young boy are gone.

“He was another soldier,” Emma remembered near the end of her life. “Mother’s prophecy came true.”

— Mary Pierpoint is freelance writer who lives in southern Douglas County. She is the granddaughter of Homer Claymore’s aunt.

| Here are excerpts from letters written home by B-17 pilot Homer Claymore. For more than 60 years, they have been carefully preserved by his family. They showed his concern for his family even as he faced death on a daily basis.June 5, 1944Dear Mother,Well here I am late as usual. Note my new address, I’ve moved again. I’m back in my old squad again.My arm is all healed up now so I’ve been flying a few practice missions.The weather sure has been swell lately, nice and cool sunny days. It never gets very warm here. If it did it sure would be bad because it’s so damp all the time … I received your last package with oysters and the Indians at work. The oysters sure were good. We got some canned milk and made stew. We sure enjoyed it … don’t feel that you have to send something every time I request it.That’s all for now.Love,HomerHis last letter, written June 13, 1944, five days before he was killed, was to a younger cousin.Dear Forrest,Thank you for your invitation to your graduation. I sure wished I could have been there. Mother wrote me a letter telling me all about it. I can’t hardly picture you graduating from high school. It seems only a short while ago I was chasing you home for meals at Pine Ridge and taking Bucky’s thumb away from him.You picked a heck of time to graduate. You don’t have much choice Army, Navy or Marines is about all the choice you have now days. I guess I should put in a plug for the Air Force along about here but I won’t.With a little luck and work you can get a lot out of any service. I hit it pretty lucky I’ve got an education that money couldn’t buy. With a little more luck I should be able to put it to some good use after this is all over.I suppose you’re all following the papers pretty close now that the big show is on over here. I have a ringside seat so to speak. I wish I could tell you more about it and my part but censorship is pretty tough now.My wound wasn’t very bad. I’m back on the job now. It wasn’t as bad as it sounds I was lucky. Some ain’t.I imagine the weather over there is nice this time of year. We very seldom see the sun over here but it is quite pretty everything is very green and flowers grow any and every where.Well congratulations again on your graduation.Love to all,Homer |