Deaf baseball player’s contributions honored

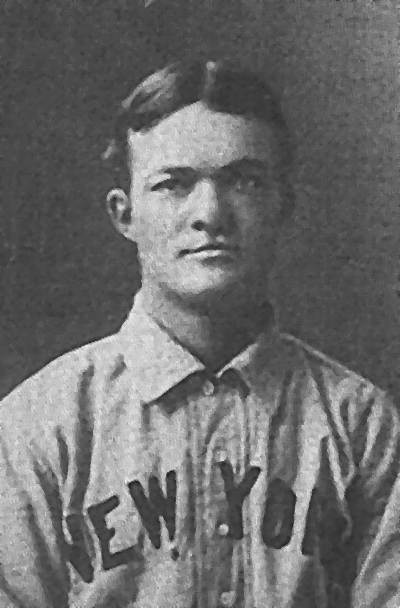

Luther Dummy Taylor

His name isn’t well known, but Luther “Dummy” Taylor’s impact on the game of baseball is eternal.

Taylor left his mark, or sign, on the game during his nine years in the major leagues. He was born deaf and was given the nickname “Dummy,” which was common in the early 1900s for deaf people.

“That’s kind of tragic, that they used to call them dummy,” said Merle Venable, longtime Baldwin City resident and avid baseball fan.

Taylor’s significance to the game of baseball can be found at every contest today. Because he was deaf, he had to use sign language to communicate with his coaches.

Although signs were being used slightly before Taylor reached the major leagues, his impact on the game was never forgotten.

Taylor, who is buried in Prairie City Cemetery in Baldwin City, was honored at the Kansas City Royals game Saturday on Luther Taylor Day at Kauffman Stadium. It was co-sponsored by the Royals and Deaf Cultural Center.

“You couldn’t stop Luther Taylor for anything,” said Bette Rogers, executive director of the Deaf Cultural Center. “It stopped raining right before the game. We had sponsors out on the field. It was a day of a lifetime.”

A ceremonial first pitch was thrown out in Taylor’s honor. His great nephew Greg Baird caught the pitch thrown from Chuck Theel, a teacher at the Kansas School for the Deaf.

The Royals also showed a video after the first inning highlighting Taylor’s life and career. The national anthem and “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” were also signed during the game as part of the historic day.

“It was a way to introduce everyone to a very good way of communication,” Rogers said. “It was wonderful when those two people signed the national anthem and seventh inning stretch.”

Taylor was born in Oskaloosa in 1875 and attended the Kansas School for the Deaf from 1884 to 1895 in Olathe. Before moving to Olathe, the school was in Baldwin City for years.

He pitched for the New York Giants for nine seasons. In his second season, he hurled a 15-inning shutout. He won 116 games during his career and lost 106.

On May 16, 1902, Taylor pitched against his deaf predecessor, William Ellsworth “Dummy” Hoy. That was the only day in major league history when two deaf pitchers faced each other.

Taylor went on to compile a 51-30 record from 1905-1908. He also won a World Series ring in 1905, despite not pitching in the championship series.

He never let his disability keep him from enjoying the game. He was often noted for gesturing to umpires, but that backfired during one game.

When an umpire refused to call a game during the rain, Taylor ran into the clubhouse and returned to the field with a yellow umbrella and rubber boots. Umpire Hank O’Day screamed at Taylor, who was clowning in the first base coaching box. Taylor ignored him but made an uncomplimentary remark in sign language about O’Day. Unfortunately, the umpire was raised by deaf parents and knew sign language. Taylor was ejected and fined $25.

Taylor was known for joking around during his career. After he played in the minor leagues for several seasons, he returned to coach five different sports at the Kansas School for the Deaf.

He also went on to teach at a deaf school in Iowa and Illinois. He retired in 1940, but became a scout for the Giants and even opened a barbershop. Taylor died Aug. 22, 1958, after a heart attack.

“He wasn’t just a great man and he wasn’t just a great deaf man,” Rogers said. “He was a great deaf ball player. We’re going to make sure his legacy lives on. We want him in the baseball Hall of Fame.”