KU’s oldest museum, filled with casts of classical sculptures and artifacts, is a ‘hidden gem’

photo by: Bremen Keasey

A plaster cast of the Venus de Milo statue at the Wilcox Classical Museum at the University of Kansas. The museum, founded in 1888, is not well-known by many at KU's campus, but curator Philip Stinson believes its history and collection makes it a "hidden gem."

Tucked away inside a corner of the University of Kansas’s Lippincott Hall is a little-known museum called the Wilcox Classical Museum. How little known is it?

“I run into people on campus who have been working for KU for decades and decades who have never heard about it. It’s not unusual,” said Philip Stinson, an associate professor of classics at KU and the curator and director of the Wilcox Classical Museum.

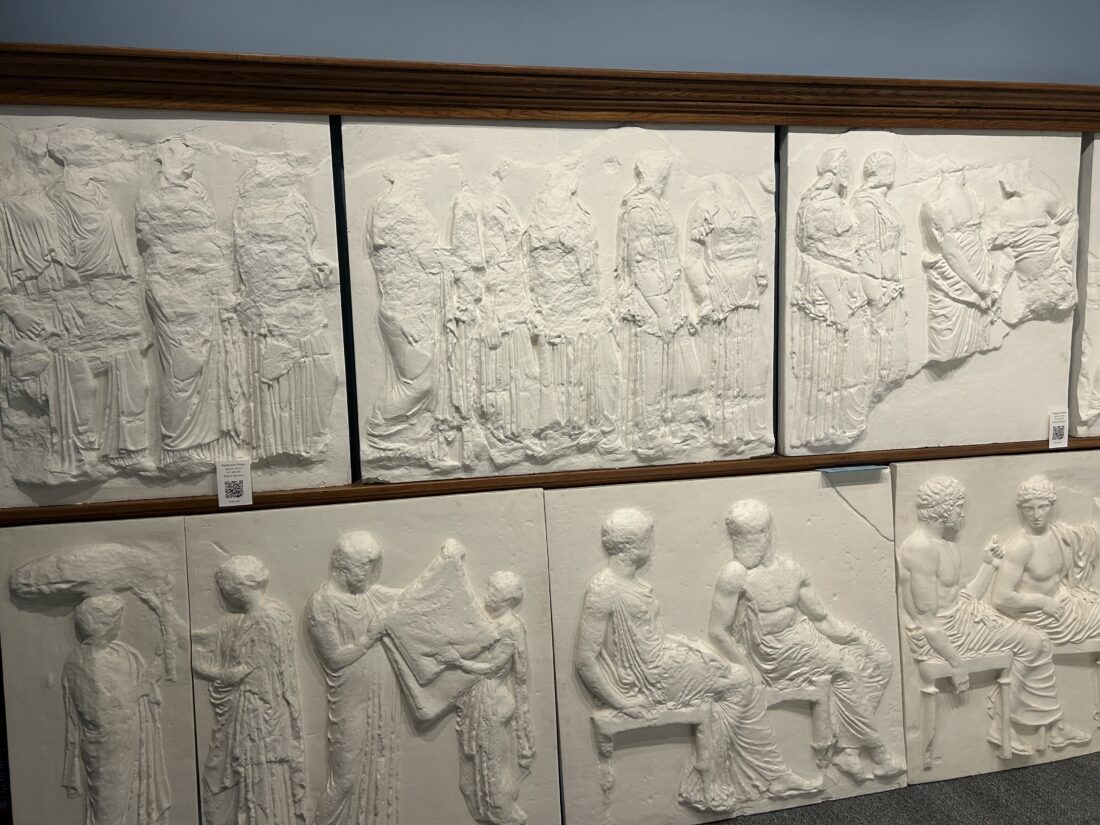

But step inside the entry way of the museum that takes up a just couple of rooms on the left side of the first floor of Lippincott Hall, you’re greeted by an array of imposing Greek and Roman statues and engravings, including the Venus de Milo, the Nike of Samothrace, portions of the Parthenon Frieze and the Apollo Belvedere — or at least their lookalikes made of plaster casts and scale reproductions.

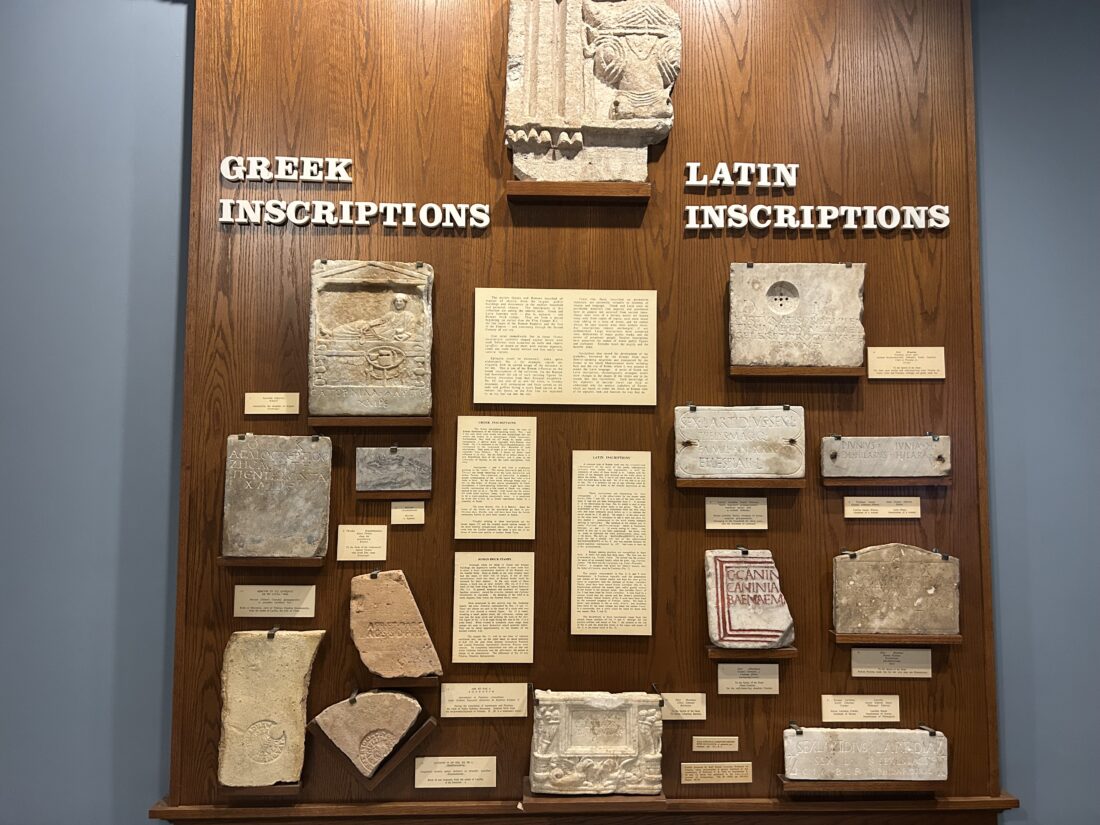

Along with those, the collection includes hundreds of different artifacts, including ceramics, coins and fragments of marble inscripted in Greek and Latin.

“I would say it’s a hidden gem,” Stinson said.

Although the museum is not well trodden, its unique history as KU’s oldest museum and its collection can be viewed as a starting point for how academic studies like archaeology or art history grew. And while it has an interesting past, Stinson is hoping to work to ensure it has a positive future.

photo by: Bremen Keasey

A plaster cast taken from a scale model of the Nike of Samothrace is displayed in a collection of the Wilcox Classical Museum at the University of Kansas, featured in the center of the picture. The museum, KU’s oldest, has collections of hundreds of artifacts as well as plaster casts of many famous Classical Greek sculptures.

The Glory Days for the Museum and Plaster Casts

While the museum currently might not ring many bells to students and faculty, it was at the center of things in its heyday when it was founded back in 1888.

The museum, initially dedicated as the Classical Museum of the University of Kansas Department of Ancient Languages and Literatures, is the oldest museum in Lawrence and possibly the oldest in the state — Stinson said he he spoke with the Kansas Historical Society, they told him they could not find another museum founded before the Wilcox. In fact, Stinson said one of the few peer museums in the area that would have opened around the same time as the museum was one at the University of Missouri which eventually became the school’s Museum of Art and Archaeology.

In the 19th Century, the museums on college campuses primarily consisted of plaster casts of the Classical statues, Stinson said. In fact, KU’s museum did not begin acquiring artifacts until 1909.

In those days, the plaster casts were seen as “primary sources” for teaching students about the art of the Greeks and Romans, Stinson said. In the days before color photography was possible, the teaching of art history or archaeology primarily focused on physical specimens. Creating plaster casts of iconic statues was seen as a way to make due without having their students travel to see the originals.

“A lot of students (at universities) did not have opportunities to travel to Europe or to some of the world’s most important museums,” Stinson said. “The idea was that a plaster cast replica is the next best thing.”

Many of the plaster casts were made shortly after the statues were discovered, Stinson said, and everybody wanted one. As an example, Stinson said one of the Wilcox’s plaster casts — Hermes and Infant Dionysus — was discovered in Greece at Olympia in 1877. “Almost immediately,” Stinson said, the authorities in Greece allowed companies to come and make casts to sell to museums.

The demand for these plaster casts was such that it became like a competition. Stinson said the Wilcox Museum has archival documents that shows the museum requested funds from the chancellor in the 1890s to purchase a copy of the Hermes and Infant Dionysus statue because Mizzou’s museum already had one.

“We competed with Mizzou not only on the football field or basketball arena but in the arena of getting plaster casts,” Stinson said.

photo by: Bremen Keasey

A variety of plaster casts — including the Resting Satyr, where the originial is on display in the Capitoline Museums in Rome — of Greek and Roman statues on display at the Wilcox Classical Museum.

Stinson shared a copy with the Journal-World of an old report to the Board of Regents from what was then called KU’s Department of Latin Language and Literature from 1888. Written by a professor D.H. Robinson, he said the founding of the museum “seems to me the most notable University event of the last two years,” and said with the objects the department has on display, it “shall be able more easily and vividly to portray, not only the material perfection of the old civilization, but also the character and genius of the peoples.”

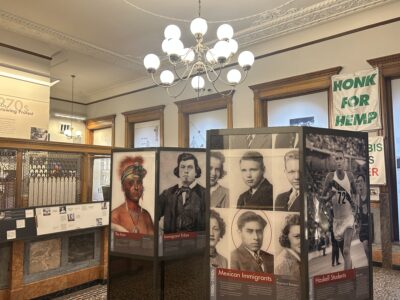

Soon the gallery, which was located at Old Fraser Hall near what eventually evolved into the Classics Department, became an important teaching and social space for all the departments in that building.

“The classical museum as it was known was a cultural center at KU during the first few decades of its history,” Stinson said.

photo by: Contributed

A scan of an old document from the Wilcox Museum that shows what a portion of its space looked like in Old Fraser Hall on KU’s campus.

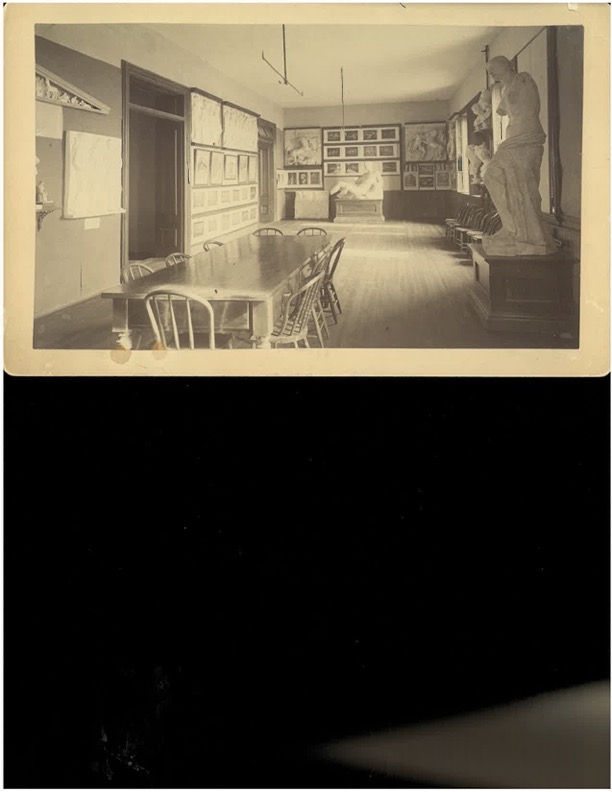

photo by: Contributed

A scan featuring a clipping of an old University Daily Kansan article from 1949 that details the Wilcox Classical Museum.

The Dark Ages — The Collection in Storage

But much like the actual statues themselves, the plaster casts had a Golden Age then suddenly became buried — this time in bureaucratic tape.

Plaster casts “fell out of fashion” in the mid-20th Century, Stinson said, and most museums began to move the plaster casts into storage around that time.

KU followed suit, especially as the Old Fraser Hall was eventually torn down in 1965, and the collection of the Wilcox was put into storage in the 1960s.

Although Stinson said according to the Wilcox’s documents the KU administration at the time promised “to quickly find a new home,” the reality was that the statues remained buried for about two decades.

The first idea floated was to put the museum in a glass atrium in the new humanities building, but Stinson said that plan fell through due to budget cuts removing that space from the scheme. There was discussion of incorporating the museum’s collection with the Spencer Museum, but that never happened either.

It was only after the “Herculean efforts” of Professor Betty Banks in 1985 that the collection and museum was reinstalled in its current space in Lippincott Hall. During the around 20 years in storage, Stinson said many of the casts degraded, and many KU students worked to restore them to their former glory. Once those restorations were complete, the museum finally reopened in 1988.

photo by: Bremen Keasey

Fragments of marble and other stone that contain inscriptions of Greek and Latin at the Wilcox Classical Museum at KU.

The Rebirth — and Aims to Create a Wilcox Renaissance

After the turmoil of the 20th century, now that the museum is back in business, Stinson said his objective is to find more ways to use the collection in its third century of operation.

Stinson said the museum’s collection of artifacts and casts were not used “very much at all,” with very few of the pieces being published. He said one big change was to log “almost the entirety (of the museum’s)” collection on its website. That move has brought much more attention to the Wilcox and its collection than it ever has before.

The museum also aims to find more ways to engage its students — closer to its time as a cultural hub. Stinson said recently the museum has encouraged Masters students at KU to take on subjects related to the collection. It also asked the geology department to assist on testing the source of the white marble for some of the museum’s artifacts.

Additionally, Stinson said he teaches about the Wilcox as part of a Museum Studies course, where it serves as a sort of “sandbox” for museum studies and brings students to the museum for each class. Wilcox said the final project for those students is what he calls “fix this museum,” where he asks students to identify problems with the Wilcox — of which Stinson says “there are many” — and they come up with solutions for how they would address those problems.

Stinson also said the museum is assessing the materials in its collection. Last year, Stinson said the museum got a grant to test the authenticity of a few artifacts in the collection — turns out, as he had suspected, they were fake. The museum also discovered it had two pieces of ancient Egyptian burial cloth, which turned out to be gifts to the museum by Kate Stephens — a Greek professor at KU who was the first woman to chair a department. The reassessment of the collection has been a key project for the museum.

“We’re coming to grips with what we have,” Stinson said. “We’re trying to get the word out to the KU and international community about interesting pieces we have in our collection.”

But more than the review of the collection, Stinson is hoping the Wilcox Museum can be reunited with the Classics Department. Stinson said the museum is in the process of finishing a proposal that would move the museum out of Lippincott Hall and into Wescoe Hall. Stinson believes that the lack of foot traffic at the current site is one of the big reasons the museum feels “hidden away.” Moving the museum to Wescoe would not only make it more front and center for visitors, but it would make it easier to use its materials in classes.

“If it was over in (with) the department of classics, we’d have daily foot traffic and it would be much easier to utilize the collection in teaching and research,” Stinson said.

While its future still might be up in the air for changes, the Wilcox’s materials still inspire awe today. People interested in viewing the collection can visit its website to learn more. The museum, at Lippincott Hall 103, 1410 Jayhawk Blvd., is free and open to the public Monday through Friday.

photo by: Bremen Keasey

Plaster casts of panels from the Parthenon Frieze on display at the Wilcox Classical Museum at KU.