Athletes’ tendencies to ‘cluster’ in certain academic fields problematic, some say

The Journal-World looked at the majors of Big 12 basketball players, and those of teams that made the Sweet Sixteen in 2012. Several schools had an inordinate number of players majoring in areas that few other students do. At Texas A&M, for example, nearly 36 percent of basketball players study agricultural leadership and development, compared to fewer than 1 percent of all students.

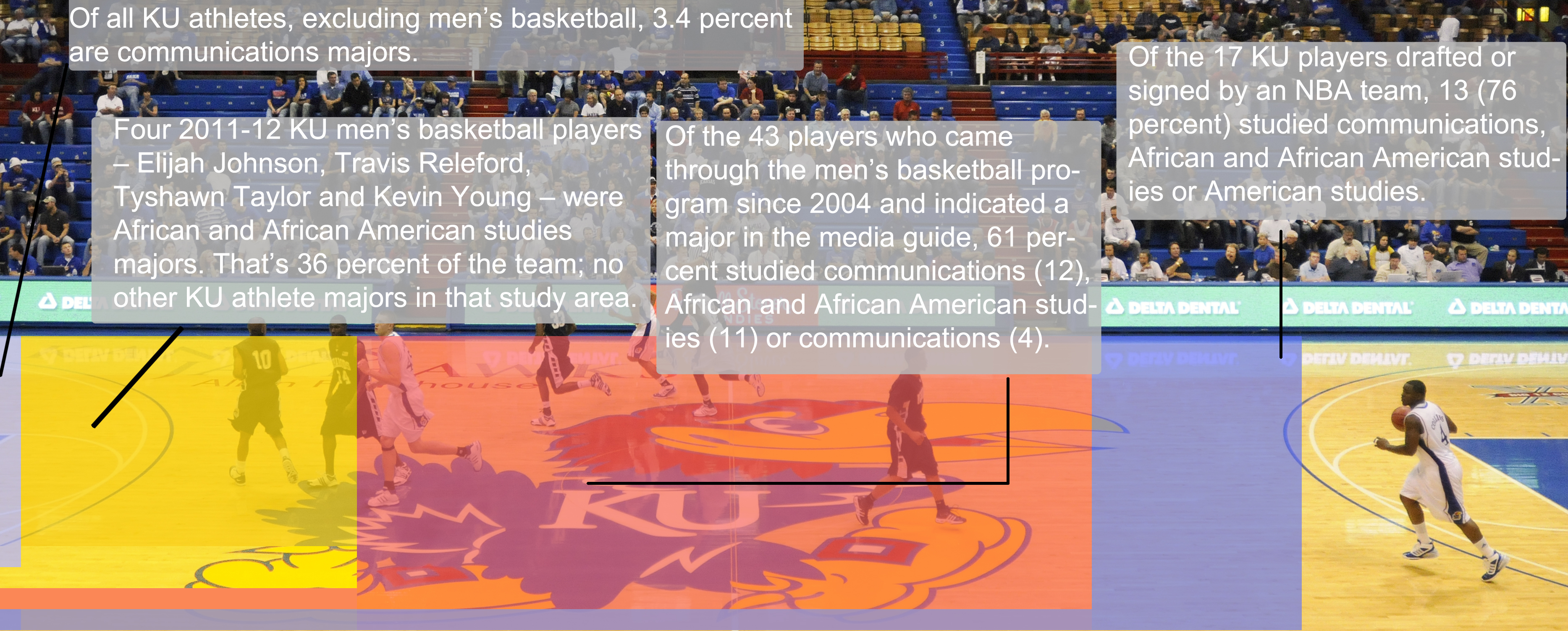

The Journal-World analyzed KU athletes' majors, as described on the KU athletics website. While just 1 percent of KU students are declared African and African American studies majors, four players from last season's men's basketball team - 36 percent of the team - majored in that study area. The numbers in this graphic only include players who indicated a major on the KU Athletics Department website rosters. Players who did not indicate a major were excluded.

The “player,” highly recruited from Miami or New York or Philadelphia, shows up on campus in Norman or Stillwater or Lawrence.

He’s ready to catch touchdown passes or throw down hammer dunks to help his team in the competitive world of college athletics in the Big 12 Conference.

A couple of years on campus, and the player expects to leave some eligibility on the table and take his talents to the NFL or NBA.

But first, there’s that college part. Surrounded by a team of tutors and advisers, the player must go to classes and maintain a certain GPA.

Not sure what to major in, player? No problem.

Maybe you should think about communications or criminal justice or African-American studies, he’s told.

See, many of his fellow players major in that. You can all take classes together. And the best part? Professor Johnson or Smith understands the pressures of big-time college athletics. They’ll take care of you. They’re big fans of the team.

You can even get an independent study course with that favorite professor. Several of the players can take it together.

Play on, player.

‘Clustering’

The situation described above is a worst-case scenario of academic major “clustering,” which happens when a large percentage of players on a sports team share a major.

An in-depth Journal-World study of Big 12 athletics, including the incoming and outgoing teams this year, found widespread clustering — defined by researchers as 25 percent of a team sharing one major — in men’s basketball and football programs.

Some of the more significant cases of clustering found in the study include:

- Baylor football team: 51 percent of players major in general studies, compared with just 1 percent of all other undergraduates. According to Baylor’s website, the program is designed for the “general career areas of health, fitness, recreation, and sports.”

- Texas A&M: 37 percent of the men’s basketball players and football players major in agricultural leadership and development, compared with less than 1 percent of nonathletes.

- Iowa State: Seven of 11 men’s basketball players majored in liberal studies.

The study also examined the majors of all Kansas University athletics teams. In the last season, student athletes’ majors appear fairly distributed at KU.

But a closer look at the KU men’s basketball team through the years tells a different story.

Between 2004 and 2012, 43 players who’ve indicated a major in media guides have passed through the KU men’s program. Of those, 61 percent have majored in communications, African and African-American studies, or American studies.

Think of the best players to come through Lawrence over the past few years, and there’s a good chance they majored in one of those three.

Mario Chalmers, TyShawn Taylor, Sherron Collins? All African and African-American studies majors.

Brandon Rush, Cole Aldrich, Julian Wright? Communications majors.

Thomas Robinson and the Morris twins? American studies.

Of the 17 KU players since 2004 who have been drafted or signed by an NBA team, 13 have majored in those same three majors.

Those majors were disproportionately high among basketball players compared with the total undergraduate student body, as well as among KU student athletes.

Such clustering, though, is not against any NCAA regulations, and it’s not even clear whether, or how, the NCAA monitors clustering.

So what’s the problem?

Clustering opens the door for potential problems, not only in terms of academic misconduct, but also for players who may never reach professional ranks, says Peter Finley, a professor at Nova Southeastern University, who’s conducted studies of clustering in major college athletics.

Athletes “become a pawn,” Finley said. “They’re there to play the sport and major in eligibility.”

For certain popular majors in college athletics “sometimes you’ll find that students in those programs can have lower GPAs, take fewer high-level courses and ‘create’ their own program, which allows them to target more professors who are ‘friends of the program,'” Finley said.

The focus when big-time athletic prospects come to campus is simply to keep them on the field, said Jason Lanter, a psychology professor and president of the Drake Group, which helps “faculty and staff defend academic integrity in the face of the burgeoning college sport industry.”

“The coach says, ‘I don’t care, make them eligible,'” said Lanter of some coaches’ attitudes toward academics.

The result is that players spend their time on campus, maybe get a degree, but in a field that doesn’t interest them and that presents little future opportunity, Lanter said.

In essence, a wasted degree.

Kansas University

Many of the schools involved in the Journal-World study, as well as the NCAA, declined comment for this article, or provided brief email statements.

Representatives from the KU Athletics Department, however, sat down for an in-depth discussion of clustering and how the department works with student athletes to choose majors.

“We have nothing to hide,” said Paul Buskirk, associate athletics director. “We are 100 percent transparent and accountable.”

Buskirk, along with Scott Ward, a fellow KU associate athletics director, explained the advising process.

Sometimes, student athletes come in with a set idea for what they want to major in. Then there’s the majority who aren’t sure, Ward said.

So those first two years on campus, they advise student athletes to focus on general education requirements and discourage students from choosing a major early, because if they change their mind, it could cause eligibility problems.

“Once you decide, you have to stick with it,” said Ward, outlining NCAA requirements that student athletes complete a certain proportion of their majors at the end of each year. Change majors, and it all gets messy.

After two years, some players still aren’t sure. That’s when more general majors, such as communications, are considered, Ward said. The ultimate goal, though, is to find majors that the players are interested in and that will make them employable when they graduate, Ward said.

And those players who plan to jump ship for the pros?

Ward knows they’re out there, but “I can’t think that way,” he said. “They’re going to be employable” when they leave.

Buskirk, meanwhile, discounted the idea that some of the majors clustered in the Journal-World study contain “easy” classes.

“There is no degree on this campus that’s a cake walk,” he said, emphasizing that the majority of courses a player takes in his college career are not from one major. “There’s no place to hide.”

The department also monitors clustering for potential problems. But its research shows no issues, Buskirk said.

“It’s an honest program,” he said.

It may be an honest program, but the numbers don’t lie; clustering happens on the KU men’s basketball team and across the Big 12.

Logical

The Journal-World study found clustering in only two other KU sports teams: football and women’s soccer.

On the football team, 17, or 26.5 percent, of 64 players who had indicated a major on the online roster majored in one of the business school’s specialities, such as finance or accounting. However, that percentage isn’t far off from the 15.7 percent of all KU athletes who major in business.

It’s a quick logical trip to explain the clustering found on the women’s soccer team, where 11 of 23 players majored in community health or exercise science. A little common sense would predict that student athletes, having played sports all their lives, might choose sports or fitness-related majors like community health or exercise science at higher rates than nonathletes.

The same holds true for the men’s basketball team, Buskirk said.

Communications is a fit for athletes who might want to pursue sports coaching or sports broadcasting, he said.

For those KU men’s basketball players who choose African and African-American studies, there’s also a logical answer.

All of the KU players since 2004 who chose that major are themselves black. They show up in Lawrence, a predominantly white community, oftentimes from cities with high black populations. That dynamic interests them, Buskirk said.

“It’s part of who they are,” he said.

There are other more head-scratching examples across the Big 12.

At Oklahoma State, for instance, 34 percent of the football team majors in education. Though OSU has a large education school, 10 percent of undergraduates are education majors; the numbers are still disproportionate.

Marilynn Middlebrook, OSU associate athletics director, said there’s a logical conclusion there as well.

“They want to stay in football” as coaches, and choose education, Middlebrook said.

“I don’t think ours is a clustering issue,” she said.

What about Texas A&M, with 37 percent of football and basketball players majoring in agricultural leadership and development?

According to the school’s website, the program is designed for those who plan to venture into the world of crops and farming. In Texas, that makes sense.

But many of the basketball players who choose that major come from places associated with anything but agriculture.

There’s guard Dash Harris, from Los Angeles; forward David Loubeau, from Miami; and guard Naji Hibbert, from Baltimore.

Representatives from Texas A&M declined an interview request, but did provide an email statement.

“There are a number of agriculture majors who are doing well in their respective fields and careers. The variety of these degree paths provide many options for our students, as well as our student athletes,” said John Thornton, interim director of athletics, in the statement. “It is not the specific degree that makes the student, but it is what the student does with that degree.”

Answers

So what’s left are those universities who see no problems with clustering in their programs, despite the numbers, along with the NCAA, which isn’t publicly sounding alarm bells.

Then there are those in the academic community, such as Finley and Lanter, who worry that big-time college athletics’ open secret of clustering leaves student athletes ill-prepared for a world outside of the field or court.

“Do they really have academic freedom?” said Lanter, who is concerned that athletics programs use a player for his gifts, but fail to live up to their end of the bargain. “What’s really going on here?”